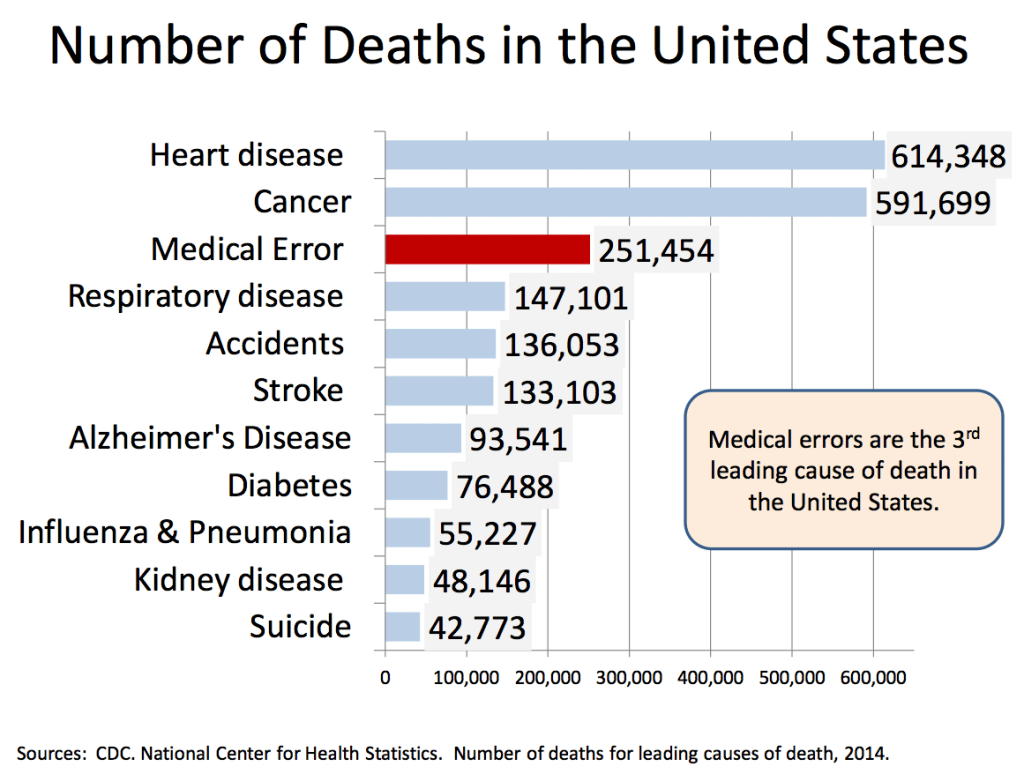

Iatrogenesis – 3rd Leading Cause of Death in US

Meriam-Webster defines iatrogenesis as “inadvertent and preventable induction of disease or complications by the medical treatment or procedures of a physician or surgeon” (Iatrogenesis, n.d.)

The following excerpt is from Marc Micozzi’s Fundamentals of Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Medicine:

In 1847, partially in response to the acceptance and success of homeopathy, and after prior attempts, a group of regular physicians founded an organization to serve as the unifying body for orthodox medical practitioners. The American Medical Association (AMA), initially under Nathaniel Chapman, was founded in Philadelphia. Physicians who belonged to the AMA considered themselves regular practitioners and adhered to therapeutics termed heroic medicine (Rutkow and Rutkow, 2004). Their invasive treatments distinguished these regular doctors to their patients. They often consisted of bleeding and blistering in addition to administering harsh concoctions to induce vomiting and purging. These treatments at the time were considered state of the art.

The justification behind such harsh treatments was a commitment to a scientific materialist medical theory, actually moving away from empirically based, “rational” medicine. Regular doctors did not share belief in the concept of the healing power of nature (the vis medicatrix naturae), and felt that a physician’s duty was to provide active, “heroic” intervention. Despite this attitude, patients recovered notwithstanding their treatments. This reality had the ironic effect of encouraging both regular doctors’ belief in heroic treatments and natural doctors’ belief in the inborn capacity for self-healing, despite the further injuries caused by many regular treatments. Much like physicians today are pressured to provide an active treatment that may sometimes be unnecessary (such as prescribing an antibiotic for a viral infection), regular doctors of the 1800s also felt pressure to give the heroic treatments for which they were known. James Whorton (2002) wrotes, “it was only natural for MDs to close ranks and cling more tightly to that tradition as a badge of professional identity, making depletive therapy the core of their self-image as medical orthodoxy.”

Although the AMA initially held no legal authority (like the multiplying medical subspecialty practice associations of today), it began a major push during the second half of the nineteenth century to create legislation and standards of medical education and competency. This process culminated in 1910 with the publication of Medical Education in the United States and Canada, compiled by Abraham Flexner (Fig. 21.2), also known as the Flexner Report. It has been described as “a bombshell that rattled medical and political forces throughout the country” (Petrina, 2008). It criticized the medical education of its era as a loose and poorly structured apprenticeship system that generally lacked any defined standards or goals beyond commercialism (Ober, 1997). In some of his specific accounts, Flexner described medical institutions as “utterly wretched … without a redeeming feature” and as “a hopeless affair” (Whorton, 2002). Many regular medical institutions were rated poorly, and most of the irregular “alternative” schools fared the worst. After this report, nearly half of the medical schools in the country closed, and by 1930 the remaining schools had 4-year programs of rigorous “scientific medicine.”

Following the Flexner Report, a tremendous restructuring of medical education and practice occurred. The remaining medical schools experienced enormous growth: in 1910 a leading school might have had a budget of $ 100,000; by 1965 it was $ 20 million, and by 1990 it would have been $ 200 million or more (Ludmerer, 1999). Faculty were now called on to engage in original research, and students not only studied a curriculum with a heavy emphasis on science, but also engaged in active learning by participating in real clinical work with responsibility for patients. Hospitals became the locus for clinical instruction. As scientific discovery began to accelerate, these higher educational standards helped to bridge the gap between what was known and what was put into practice. More stringent licensing and independent testing provided a greater degree of confidence in the competence of the nation’s doctors. During this same time period, the suppression and decline of alternative schools of health care occurred, as both public and political pressure increased.

The 1910 Flexner Report, sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation, compared all American medical schools against a standard represented by the new Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, which had been founded in 1888. Criticism was so devastating that about three-quarters of American medical schools closed, including many osteopathic medical schools.

Bernarr Macfadden, founded the “physical culture” school of health and healing, also known as physcultopathy. This school of healing gave birth across the United States to gymnasiums where exercise programs were designed and taught to allow individual men and women to establish and maintain optimal physical health.

Although so strongly based on common sense and observation, many theories exist to explain the rapid dissolution of these diverse healing arts. The practitioners at one time made up more than 25% of all U.S. health care practitioners in the early part of the twentieth century. Low ratings in the infamous Flexner Report (which ranked all these schools of medical thought among the lowest), allopathic medicine’s anointing of itself with the blessing “scientific,” and the growing political sophistication of the AMA clearly played significant roles. Of course, the acceptance of the germ theory of disease and development of effective antibiotics for the first time provided a strong rationale for the new, “scientific,” regular medicine.

Additionally:

Whatever the validity of medical critiques, the American medical establishment’s policy on chiropractic was not that of a disinterested group seeking to serve the public health and well-being. A century-long campaign against chiropractic impeded medical advancement and at times posed a severe threat. Until relatively recently, allopathic medical students were taught that chiropractic is harmful, or at best worthless, and they in turn passed along these prejudices to their own patients.

A staunchly antichiropractic policy was pursued by the American Medical Association (AMA). In 1990 the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed a lower court ruling in which the AMA was found liable for federal antitrust violations for having engaged in a conspiracy to “contain and eliminate” (the AMA’s own words) the chiropractic profession (Wilk v. AMA, 1990). The process that culminated in this landmark decision began in 1974 when a large packet of confidential AMA documents was provided anonymously to leaders of the American Chiropractic Association and the International Chiropractors Association. As a result of the ensuing Wilk v. AMA litigation, the AMA reversed its long-standing ban on interprofessional cooperation between medical doctors and chiropractors, agreed to publish the full findings of the court in the Journal of the American Medical Association, and paid an undisclosed sum, most of which was earmarked for chiropractic research. This ruling has not completely reversed the effects of organized medicine’s boycott, especially when it comes to application of the most effective and cost-effective treatments for common pain conditions.

There is good and bad in all things, depending upon the circumstances for whatever situation presents itself. If an arm is severed, a bone is crushed or traumatic injuries – get immediate medical help. If you suffer from allergies, back pain, headaches and a plethora of other non-life threatening issues – become educated as to what options are available. Be well, become healthy, be wise.

References:

Anderson, J. G., & Abrahamson, K. (2017). Your Health Care May Kill You: Medical Errors. Studies in health technology and informatics, 234, 13–17.

iatrogenesis. (n.d.). The Merriam-Webster.Com Dictionary. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/medical/iatrogenesis

Micozzi, Marc S.. Fundamentals of Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Medicine – E-Book (p. 537). Elsevier Health Sciences. Kindle Edition.

Micozzi, Marc S.. Fundamentals of Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Medicine – E-Book (p. 644). Elsevier Health Sciences. Kindle Edition.

__________