This is yet another of my posts on my scholarly research into the benefits of exercise, and more specifically methods of mindfulness (such as qigong) as treatments for mental health ailments.

Various types of traumas exist such as that of child abuse, sexual abuse, domestic violence, community violence, non-interpersonal trauma, death, or serious illness of a loved one, being bullied, physical assault, threats of aggression, exposure to combat among others. Various types of traumas can have a wide range of different psychological effects and outcomes. Potentially traumatic life events (PTLE) are negative incidents that may potentially compromise an individual’s ability to cope with a considerable amount of stress, resulting in a fear of death, destruction, or even insanity. Recent research has found that exposure to trauma is much more prevalent than previously recognized, where between 50% – 75% of individuals have encountered potentially traumatic situations. Self-medicating through use of various substances may be utilized to counter adverse psychological symptoms, however substances can also increase affective dysregulation and mental discomfort. This may lead to a vicious cycle of an increased desire to further self-medicate, creating a possible opportunity for other addictive behaviors (Levin et al., 2021).

There is evidence supporting that mindful breathing practices can be an effective alternative to using pharmaceuticals for treating those that suffer from past trauma. Mindful breathing practices encourage empowerment of the individual to be proactive towards their own wellbeing. Mindful breathing classes are becoming more popular with those suffering from trauma. While some sufferers of trauma may find mindful breathing practices to be time consuming or not worth the effort, mindful breathing practices can be effective in helping people better cope with trauma, are relatively easy to learn and practice, are generally inexpensive and available to most people.

It is estimated that more than 80% of the US population will be subject to some type of traumatic event during some time in their lives, with over 8% of those exposed going on to develop post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD (Schein et al., 2021b). While there are many types of traumas, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the most common. PTSD sufferers are more prone to experience symptoms of substance abuse, anger, irritability, depression, distractibility, irritability, sleep disorders, relationship conflicts, issues in their workplace, chronic pain, suicide, and other medical issues (Colgan et al., 2017).

A recent study reports of PTSD’s 1-year prevalence spanning from 2.6% – 6.0% with civilians and ranging from 6.7% – 11.7% with US veterans. The lifetime prevalence spanned from 3.4% – 8.0% with civilians and from 7.7% – 13.4% with veterans. Women have almost twice the 1-year prevalence of PTSD compared to men, as do veterans also having roughly twice the prevalence of that of civilians. Overall estimates are quite varied due to the underdiagnosed character of this psychiatric disorder, the heterogeneity or diversity of a population, and the potential for misdiagnosis. Various subpopulations have been reported to have higher prevalence of being diagnosed with PTSD such as emergency 1st responders, American Indian/Alaska Natives, trans-masculine individuals, persons with substantial substance use, those having attempted suicide, females with previous military sexual trauma, and refugees. Additional risk factors would be young persons, females, lower income individuals, and those with mental health disorders (Schein et al., 2021b).

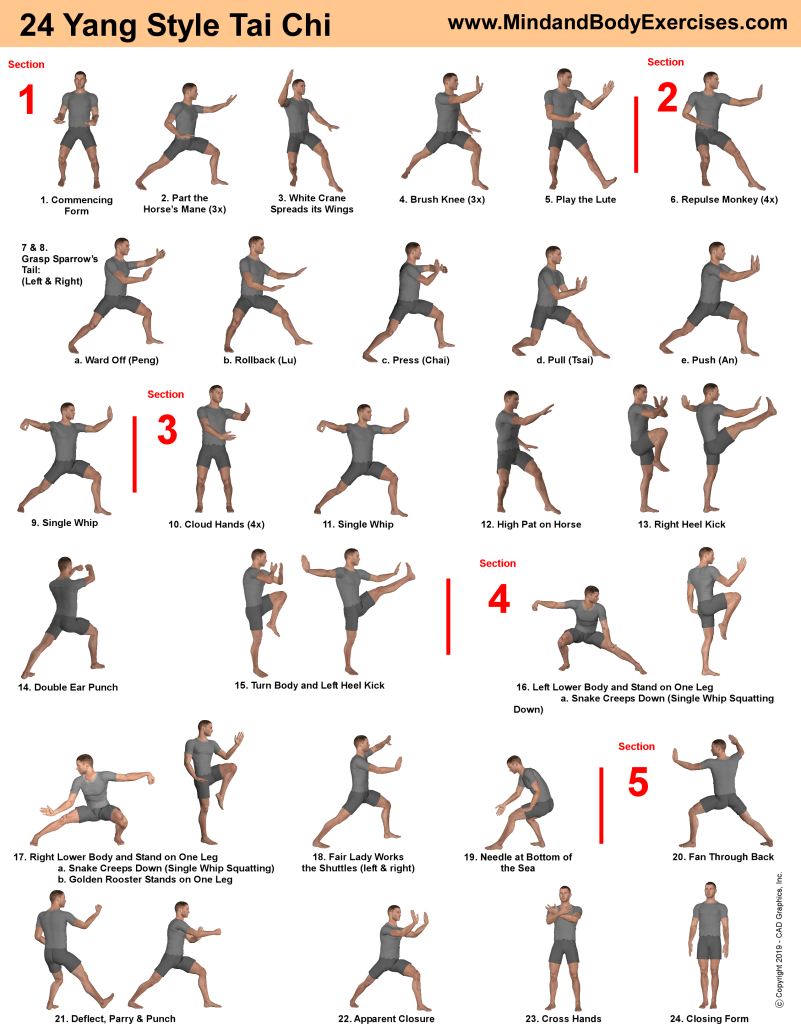

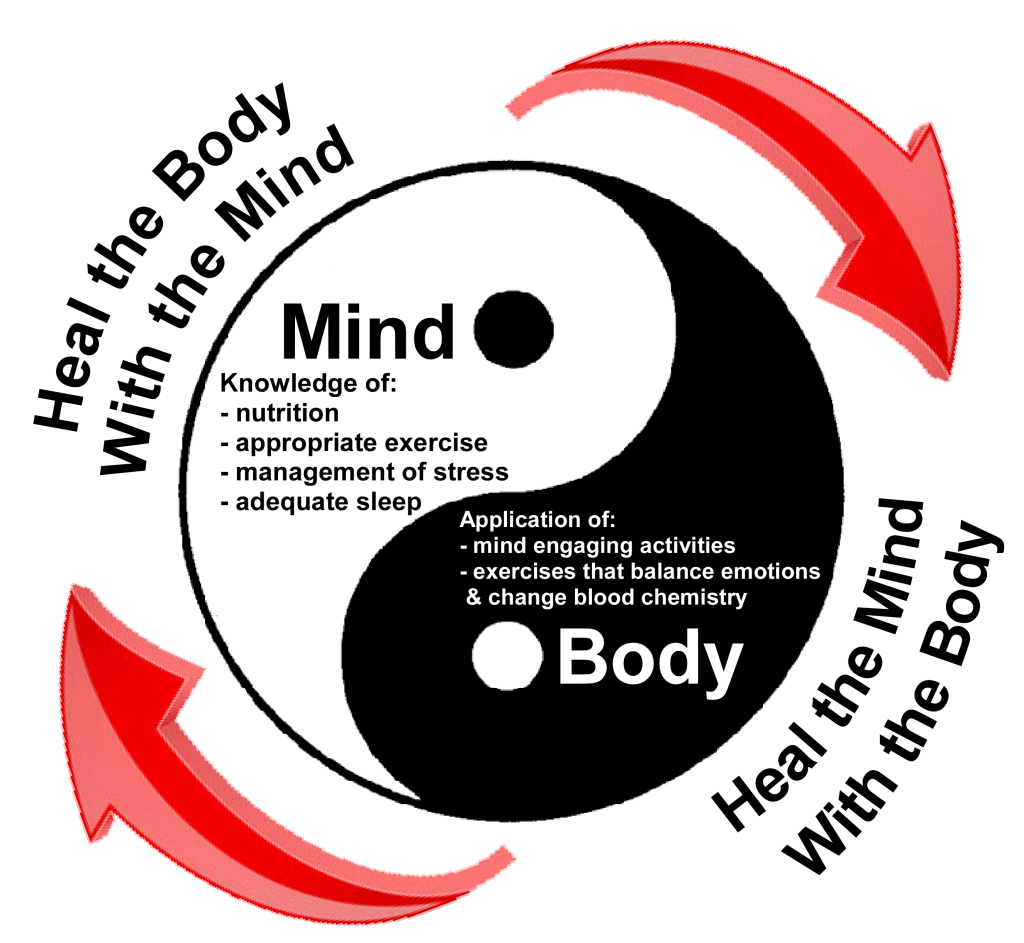

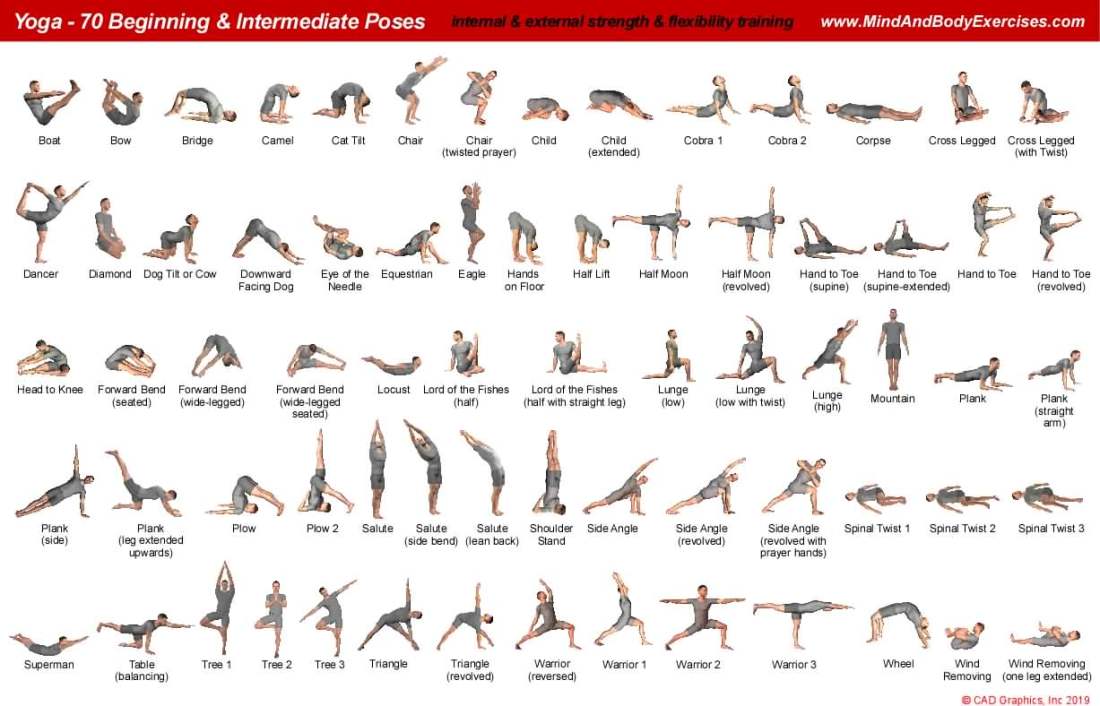

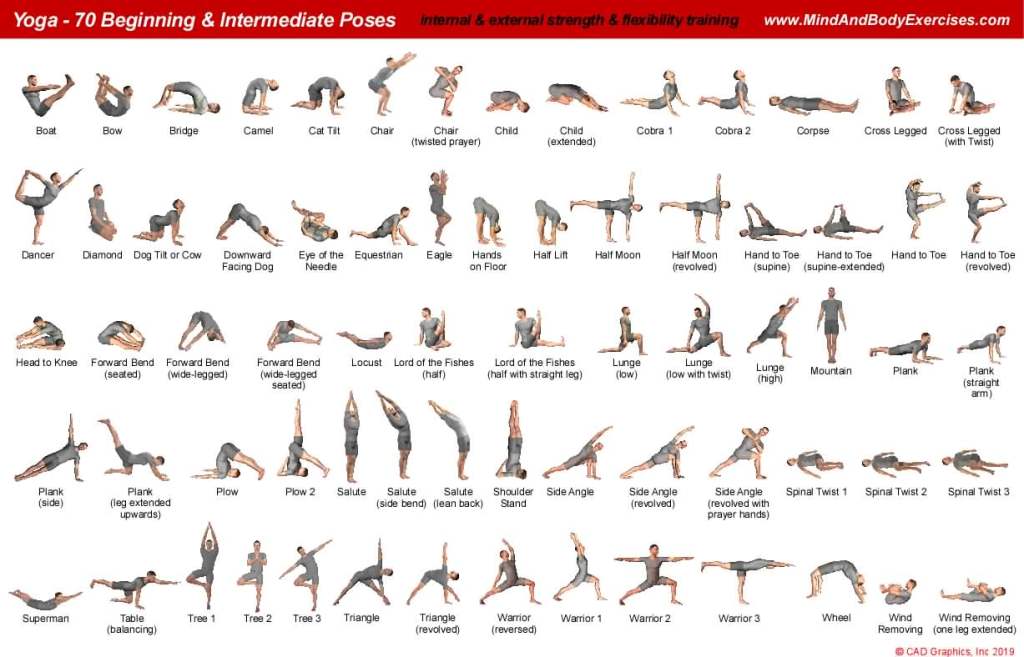

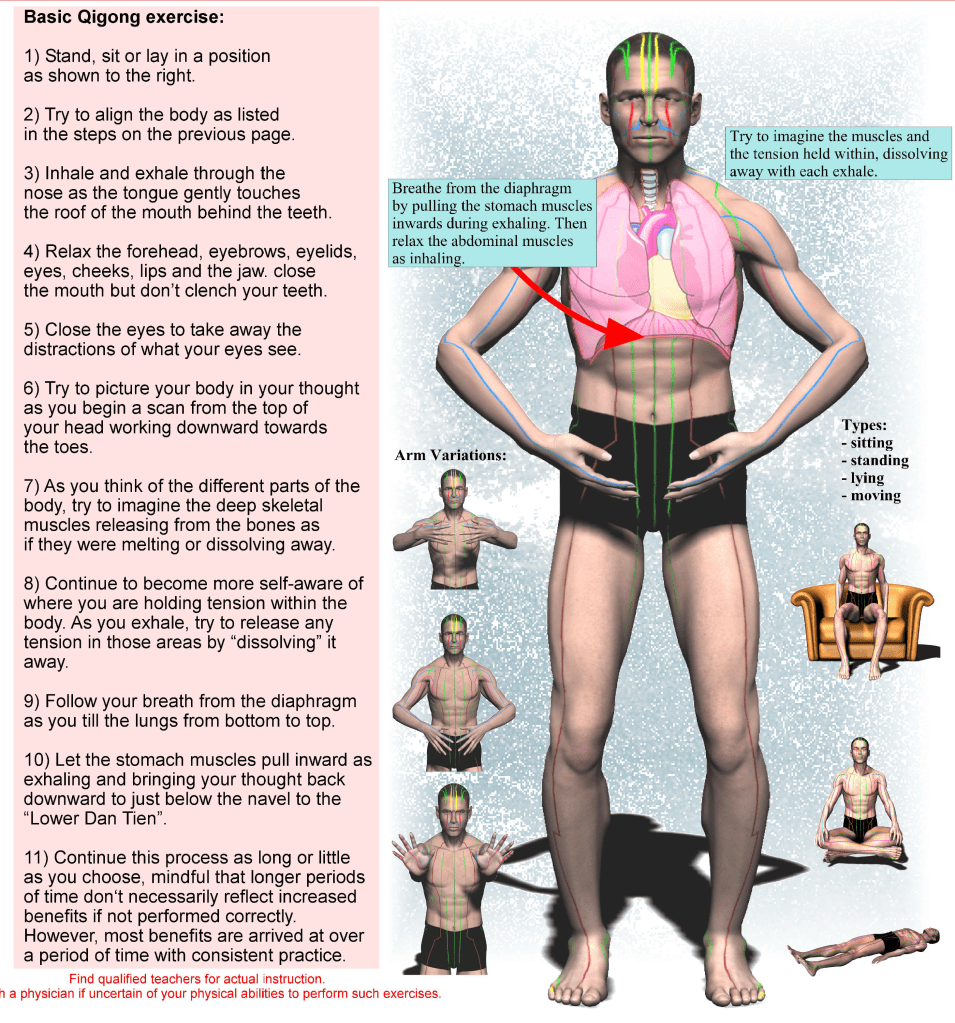

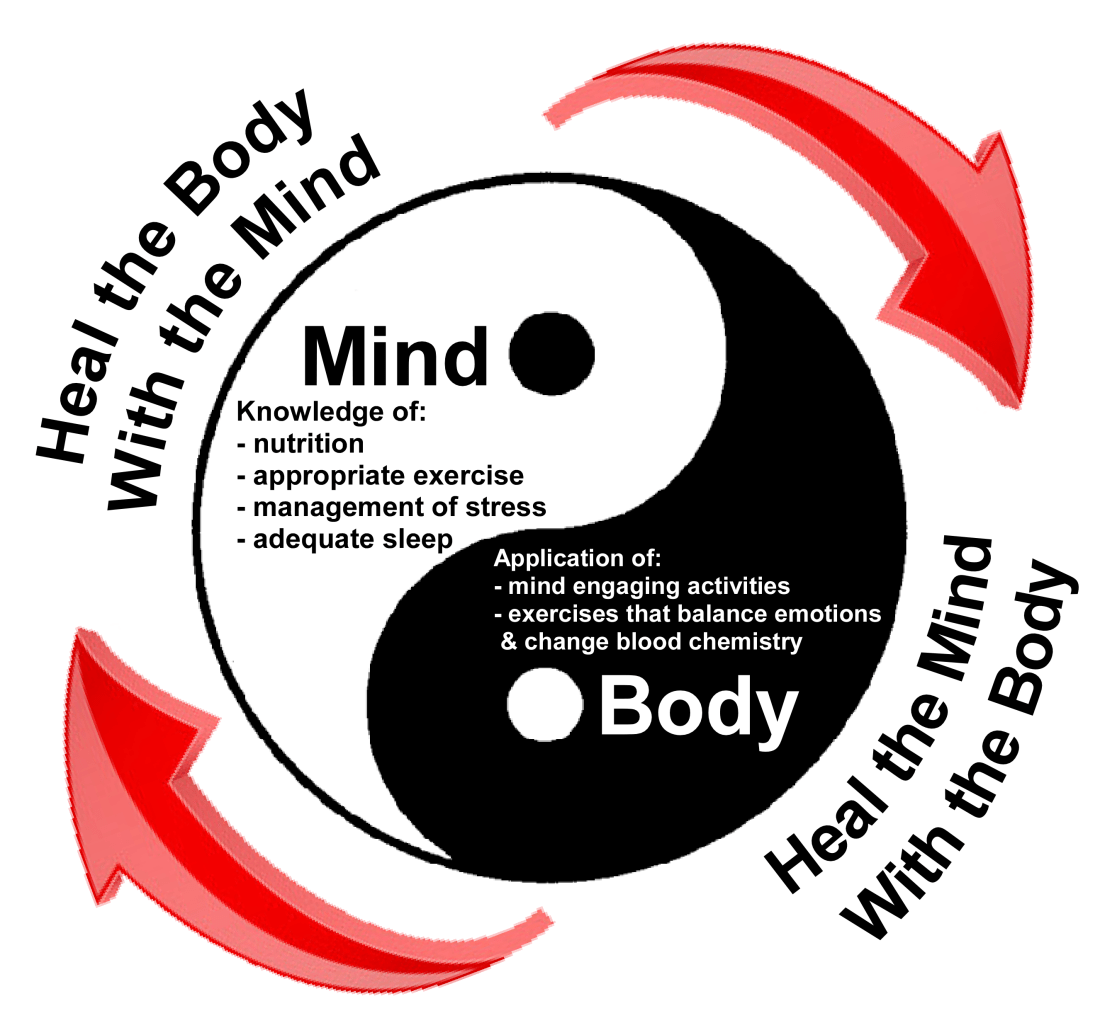

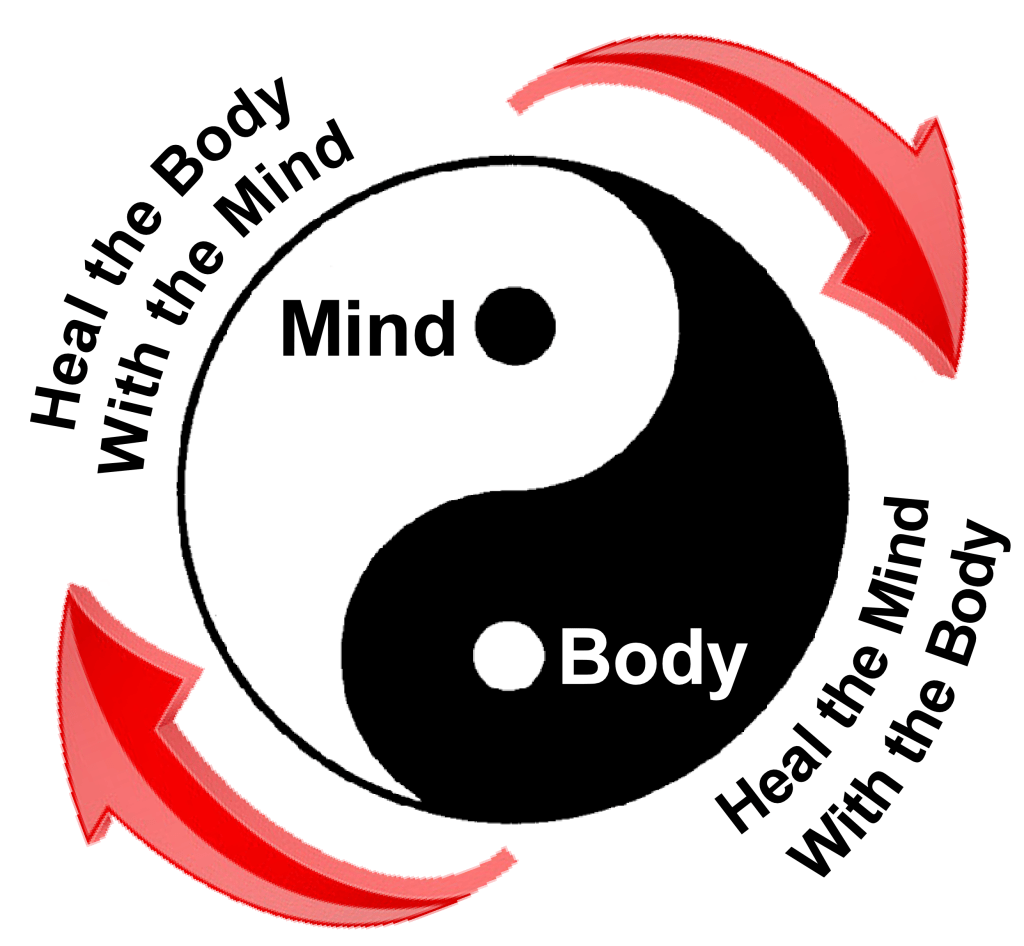

Mindfulness is based on philosophical perspectives from Buddhist teachings, where one would focus on sustaining their attention in a specific manner, with intent, without judgement, and having a purpose, while striving to be present in the moment (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Mindful based interventions (MBI) are rooted in methods that had been distilled over thousands of years in Eastern philosophies. Most of these methods require the individual to become strongly motivated to commit to making conscious changes in their everyday lives (Marzillier 2014). Researchers have classified 12 various categories of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) which would include focused attention, redirecting disturbing thoughts of events, letting go of negative thoughts, emotions, or physical pain. Also, relaxing/calming and slowing down, coping with sleep disorders, thinking logically and rationally, mantra techniques, reduction in flashbacks, sharing of thoughts and feelings more constructively, and self-awareness of spirituality (Colgan et al., 2017). MBI methods also may include breathing-based meditation (with rhythmic breathing), mindfulness meditation (participants strive to remain present), compassion meditation (loving‐kindness meditation) and Transcendental meditation (practitioners repeat or focus upon a mantra) (Haider 2021). Consistent practice with personal experience in applying mindfulness to one’s own life on a daily basis, is a basic requirement that is found with all the MBIs. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has integrated basic techniques from yoga and meditation to the benefit of people who had never imagined implementing such methods (Marzillier 2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) was first introduced by John Kabat-Zinn, focuses on the practice and refinement of mindfulness techniques, specifically of sitting meditation, body scanning, and mindful movement of the body with methods of yoga and tai chi (Reangsing 2021). It is important to note that not all mindfulness-based interventions are considered as being yoga, tai chi and qigong. However, by their definition yoga, tai chi and qigong are mindfulness-based interventions in that they all utilize within their practices the concept of mindful breathing (MB). MB is basically where the practitioner attempts to bring sustained awareness to their breath as it enters through their nostrils and then rises and falls in their lungs with each following respiration. There are many more methods that vary in their specific benefits and relative complexity.

A study was conducted for 6-weeks as part of a bigger study at the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) Neurology Department ongoing from 2009-2013, with 102 veterans (96 males and 6 females) having been previously diagnosed with chronic PTSD and averaging 52 years of age. The goal of this study was to research the physiological benefits of slow breathing (SB) compared to mindfulness, in people with PTSD. The participants were tasked with engaging with 1 of 4 mindfulness methods consisting of mindful breathing (MB), slow breathing, body scanning (BS) or sitting quietly (SQ). Participants using MB techniques used a tape or CD of a 20-minute guided meditation, where they were to practice daily at their homes. They were directed to sit upright while attempting to bring their awareness to that of their breath as it entered through the nostrils and then fell to their chest and abdomen. If their focus strayed from the breath, they were directed to just acknowledge the distracting thought, allow it to pass, and then return awareness to their breath. The study results reported six key benefits from the participants’ responses, which consisted of a greater ability to relax, an improvement in coping skills, an enhanced awareness of being in the present, an increase in nonreactivity, an improvement in nonjudgmental acceptance, a reduction in stress reactivity and less physiological arousal. The participants in the body scan and mindful breathing groups, reported more positive benefits in reducing PTSD symptoms, then those in the slow breathing or quiet sitting groups (Colgan et al., 2017).

A randomized control trial from 2014 included 21 US veterans diagnosed with PTSD. Participants were introduced to breathing-based meditation utilizing Sudarshan Kriya Yoga, where they took part in a 7-day, 21-hour total intervention with a daily group yoga class lasting for 3 hours. At the end of the intervention, members reported reductions in anxiety symptoms, and a lower rate of breathing. In a similar study with 102 veterans in 2016, participants were randomized to 3 different types of MBI being that of sitting quietly (SQ), slow breathing (SB), mindfulness meditation (MM), MM with SB, and SB with a biofeedback device. SB and MM groups met once a week for 6 weeks while practicing at home and on their own for 20-minintes a day. The results reported the most improvements in PTSD symptom scores in the MM group, with the next most being the MM plus SB group, followed by the SQ group and finally the SB group (Haider 2021).

Depersonalization disorder (DPD) is another condition that may result from exposure to traumatic events. Symptoms of DPD would be delusions, or a feeling of being an outside observer to one’s own actions, feelings, thoughts, and sensations, while also experiencing a detachment in regard to their surroundings. Research supports that mindful breathing may immediately help DPD patients reduce feelings of depersonalization by increasing feelings of being grounded. The theory is that by directing self-awareness towards the physical sensations of one’s own breathing while listening to particular sounds, patients become more grounded in focusing on their breathing than losing themselves in ruminative self-observation. Ruminative and detached self-observation are thought to be key components in mechanisms that regulate depersonalization. Mindfulness exercises may allocate cognitive resources to limbic and insular cortices pathways that process emotional stimuli and thereby aid in managing damaged self-awareness (Michal et al., 2013).

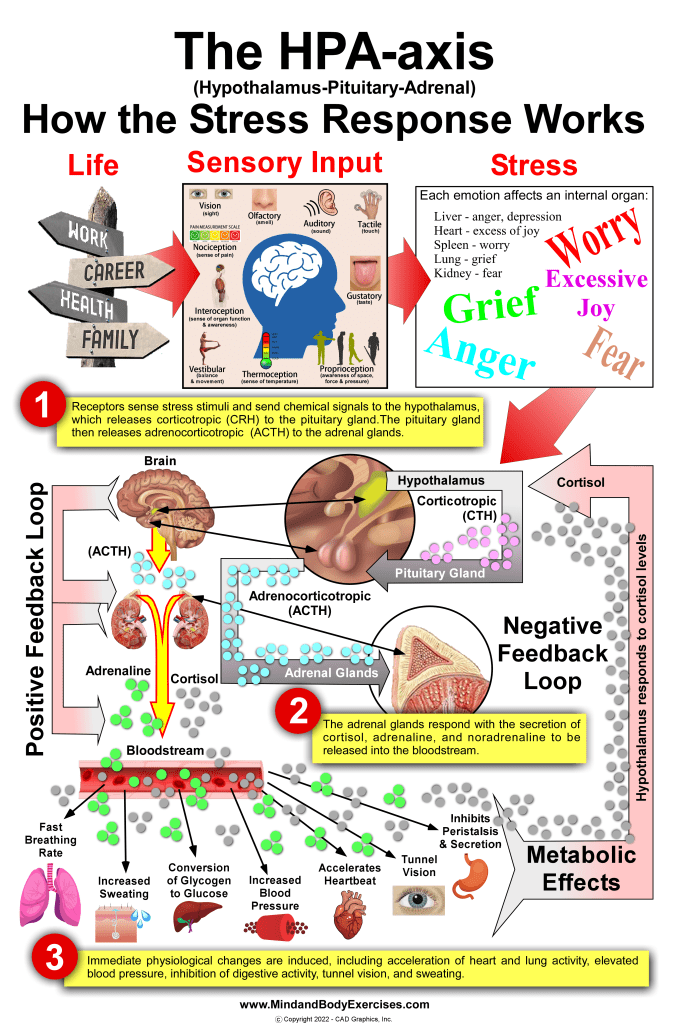

Other research finds that there is a strong correlation between reduced orbitofrontal and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) blood circulation derived from childhood emotional abuse, where individuals had experienced repetitive stressful events over a particular length of time. The orbitofrontal and vmPFC sends signals to the amygdala. There is speculation that a deficiency in consistent orbitofrontal and vmPFC activity, along with hyperactivity of the amygdala responding to repetitive stress, might be a strong indicator of being susceptible to depression. Further research indicates that healthy adults may be able to consciously control their emotions by increasing their vmPFC activity if exposed repetitively to a stressor. This is important to note that from previous research, that repeated mindful breathing over a prolonged period of time, can result in reduced agitation of areas of the brain that regulate emotional status such as the amygdala and thalamus, and imagery memory management from the hippocampus and fusiform gyrus (Wang et al., 2013).

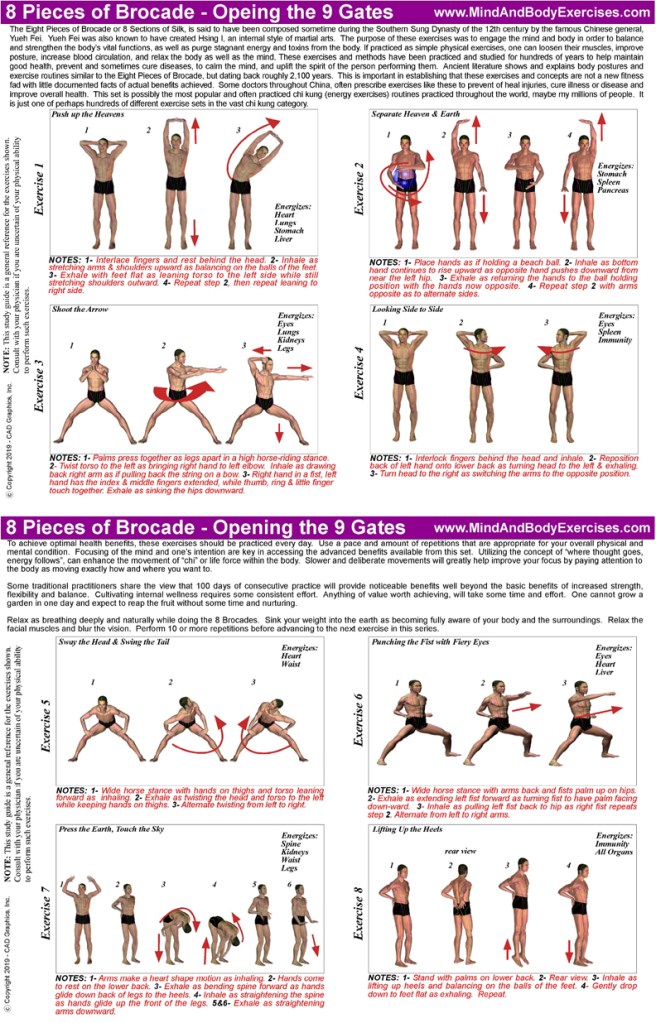

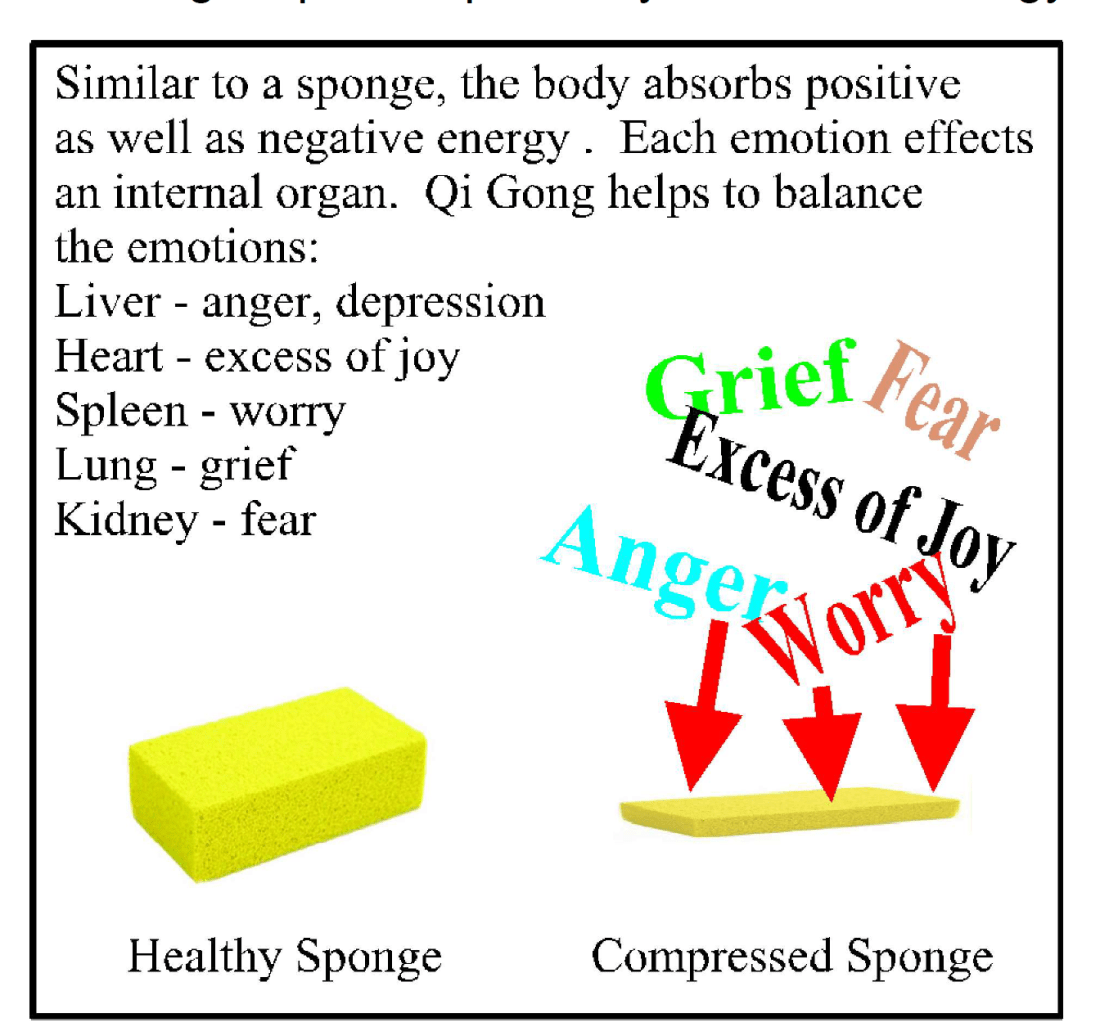

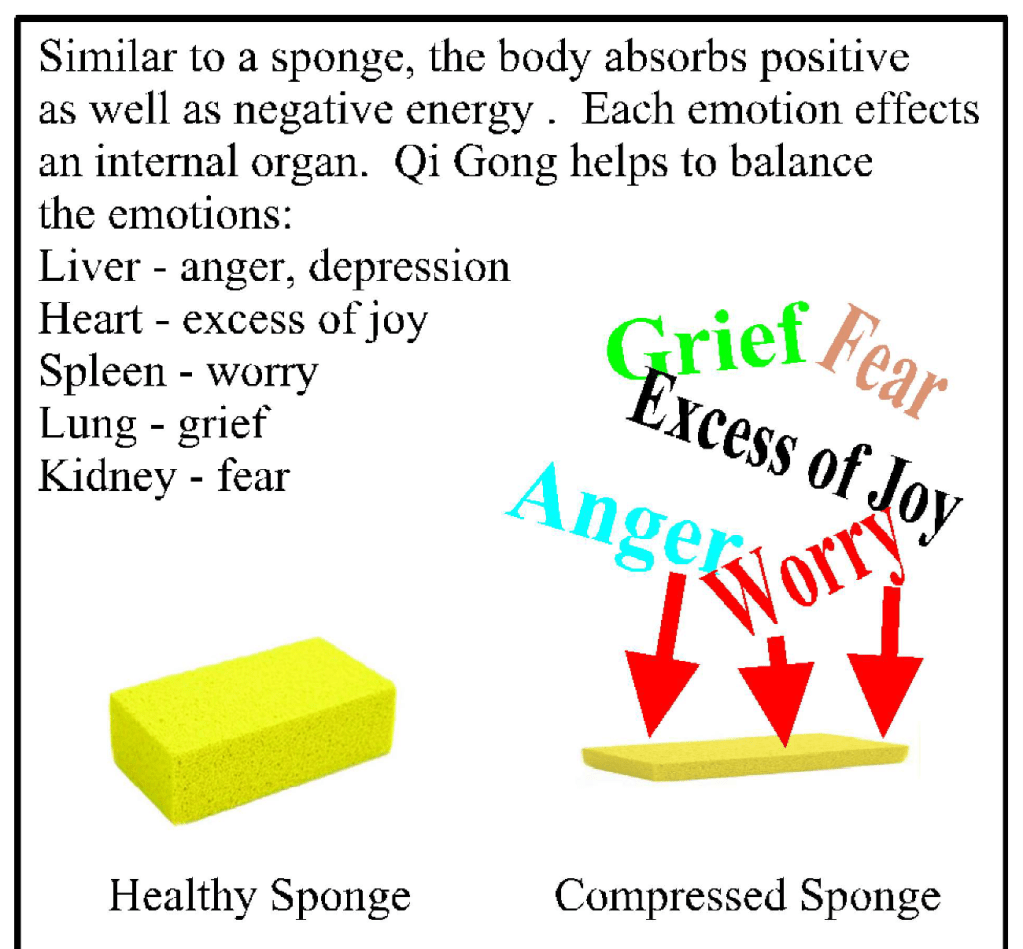

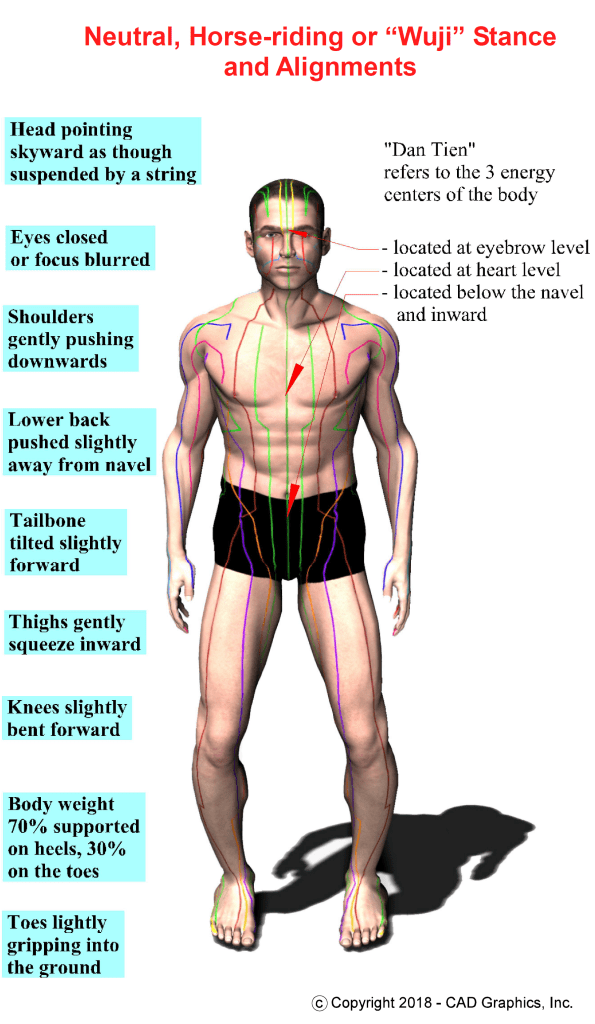

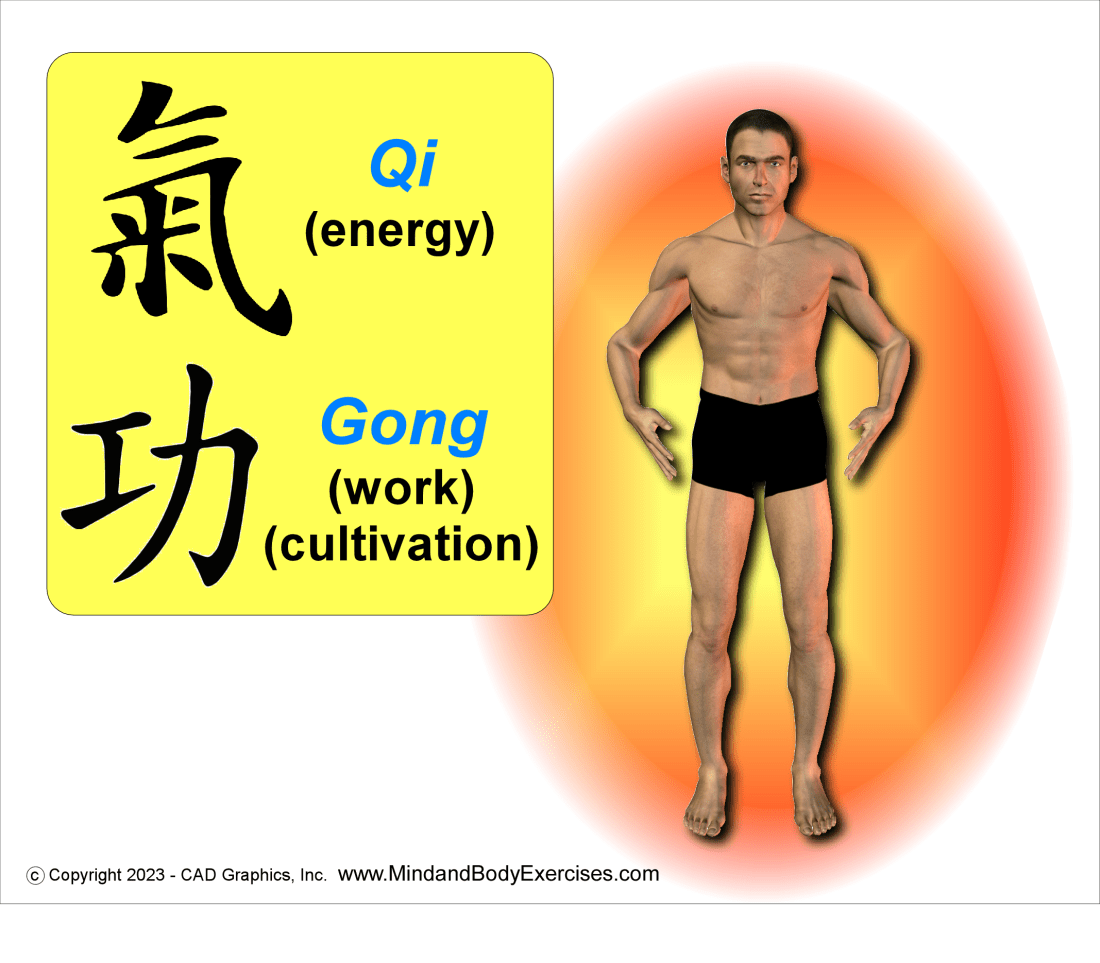

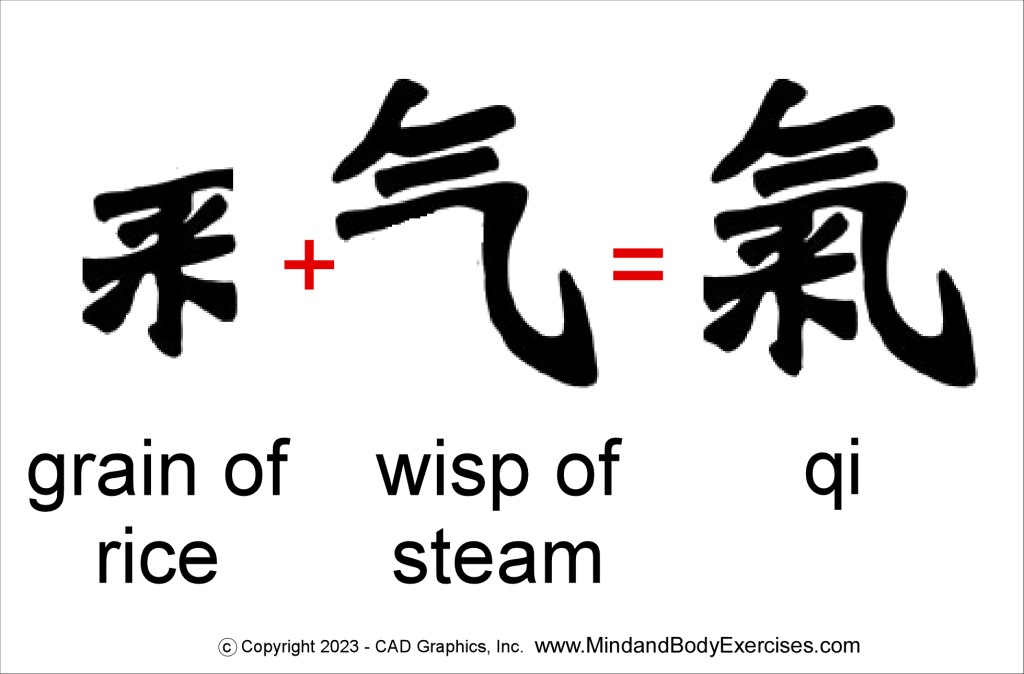

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) offers a much different perspective on trauma, from that of allopathic medicine. TCM views our life force or qi, which can become blocked, depleted, scattered, and even injured by a wide spectrum of environmental and psychological causes, such as trauma. TCM recognizes that trauma can be directly experienced and even inherited from our parents. Injuries to one’s qi from external factors as well as traumatic events, affect the energy meridians which transport qi, as well as the physiological organ systems (Aanavi, 2014). One of TCM’s branches of treatment is qigong, or literally translated to “breath work”. Taijiquan (tai chi or taiji) is perhaps the most commonly known type of qigong practice. Qigong offers a huge curriculum of traditional practices that can cultivate, increase, focus, and even heal one’s qi through specific physical exercises and deliberate regulated breathing methods. Qigong offers both medical and martial applications through mindfulness and self-awareness. Recent studies regarding Tai chi qigong (TCQ) practice reported overall high satisfaction. There were no apparent negative reactions nor side effects. In one study participants noted muscle soreness that decreased later in the treatment duration. Other reported that participants found the sessions to reduce stress, were relaxing and/or calming and showed a reduction in mental health symptoms of PTSD, such as anxiety and depression. Other studies reported of increased feelings of empowerment and control over their symptoms. Also, better sleep quality, reduction in pain, improvement in physical functioning, increased ability to focus. One study did note some obstacles in their participation, like scheduling conflicts, emotional issues, work conflicts, transportation challenges and physical or health-related limitations (Niles et al., 2022).

While these studies do offer much to contemplate regarding the many psychological and physical benefits from such practices, the data needs to be more accurately and purposefully organized and compiled. There are many more factors that come into play regarding the efficacy of mindful breathing practices that many of these studies did not address, such as length, duration, and intensity of a particular practice session. Additionally, the type or style of the methods as well as the attitude, experience, and qualification level of the instructor, and sometimes the student/patient can have effects on desired outcomes from practicing these methods. Regardless of these factors, studies do support mindful breathing practices as being an effective treatment option for coping with past experiences from trauma events.

References

Aanavi, M. (2014). Trauma, Qigong, And Trust. California Journal of Oriental Medicine (CJOM), 25(1), 23–25.

Colgan DD, Wahbeh H, Pleet M, Besler K, Christopher M. (2017). A Qualitative Study of Mindfulness Among Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Practices Differentially Affect Symptoms, Aspects of Well-Being, and Potential Mechanisms of Action. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 2017;22(3):482-493. doi:10.1177/2156587216684999

Haider, T., M.P.H., Dai, C., PhD., & Sharma, M., PhD. (2021, Winter). Efficacy of meditation-based interventions on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among veterans: A narrative review. Advances in Mind – Body Medicine, 35, 16-24. Retrieved from https://northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/efficacy-meditation-based-interventions-on-post/docview/2494554894/se-2

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Levin, Y., Lev Bar-Or, R., Forer, R., Vaserman, M., Kor, A., & Lev-Ran, S. (2021). The association between type of trauma, level of exposure and addiction. Addictive Behaviors, 118. https://doi-org.northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106889

Marzillier, J. (2014). The Trauma Therapies: Vol. First edition. OUP Oxford.

Michal, M., Koechel, A., Canterino, M., Adler, J., Reiner, I., Vossel, G., Beutel, M. E., & Gamer, M. (2013). Depersonalization disorder: Disconnection of cognitive evaluation from autonomic responses to emotional stimuli. PLoS ONE, 8(9). https://doi-org.northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074331

Niles, B. L., Reid, K. F., Whitworth, J. W., Alligood, E., Williston, S. K., Grossman, D. H., McQuade, M. M., & Mori, D. L. (2022). Tai Chi and Qigong for trauma exposed populations: A systematic review. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 22. https://doi-org.northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2022.100449

Reangsing, C., Punsuwun, S., & Schneider, J. K. (2021). Effects of mindfulness interventions on depressive symptoms in adolescents: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 115. https://doi-org.northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103848

Schein, J., Houle, C., Urganus, A., Cloutier, M., Patterson-Lomba, O., Wang, Y., King, S., Levinson, W., Guérin, A., Lefebvre, P., & Davis, L. L. (2021b). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 37(12), 2151–2161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2021.1978417

Wang, L., Paul, N., Stanton, S. J., Greeson, J. M., & Smoski, M. J. (2013). Loss of sustained activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in response to repeated stress in individuals with early-life emotional abuse: implications for depression vulnerability. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 320. https://doi-org.northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00320

I write often about topics that affect our health and well-being. Additionally, I teach and offer lecture about qigong, tai chi, baguazhang, and yoga. I also have hundreds of FREE education video classes, lectures and seminars available on my YouTube channel at:

https://www.youtube.com/c/MindandBodyExercises

Mind and Body Exercises on Google: https://posts.gle/aD47Qo

Jim Moltzan

407-234-0119