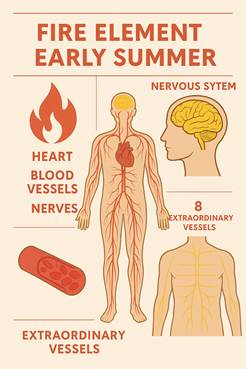

Fire Element, Circulation, and the Nervous System

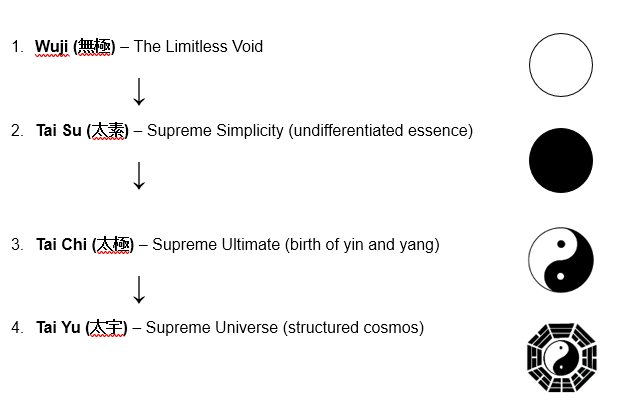

As nature enters early summer, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) views this vibrant season through the lens of the Fire element, a phase of maximum Yang, warmth, expansion, and communication. Fire governs not only the Heart and blood vessels, but also the nervous system, emotions, and spiritual awareness. This inner fire fuels both our physical vitality and our mental clarity. In this unique seasonal phase, the flow of Qi, Blood, and Shen (spirit), especially through the veins, arteries, and the Eight Extraordinary Meridians takes center stage.

Understanding the dynamic between the Fire element, cardiovascular and neurological systems, and the deeper energetic channels allows us to harmonize body, mind, and spirit during this high-energy time of year.

🔥 Fire Element and Its Associations

In TCM’s Five Phase (Wu Xing) framework, Fire is associated with:

- Season: Early Summer

- Organs: Heart (Yin) and Small Intestine (Yang)

- Emotions: Joy, enthusiasm, overexcitement, or mania

- Body Tissue: Blood vessels and the nervous system

- Sense Organ: Tongue

- Color: Red

- Climate: Heat

- Direction: South

- Taste: Bitter (Maciocia, 2005; Deadman et al., 2007)

Fire energy is expansive and expressive, symbolizing circulation, communication, and consciousness. When well-regulated, Fire fuels love, clarity, movement, and insight. When excessive, it can consume the mind and disturb the spirit.

❤️ Heart, Blood Vessels, and Nervous Regulation

The Heart (Xin) is considered the “Emperor” of the body, orchestrating the flow of Qi and Blood and serving as the seat of Shen (mind/spirit). TCM describes its functions as:

- Governing the blood and blood vessels

- Housing the Shen, which includes consciousness, thought, memory, and emotions

- Regulating mental activity and sleep (Maciocia, 2005)

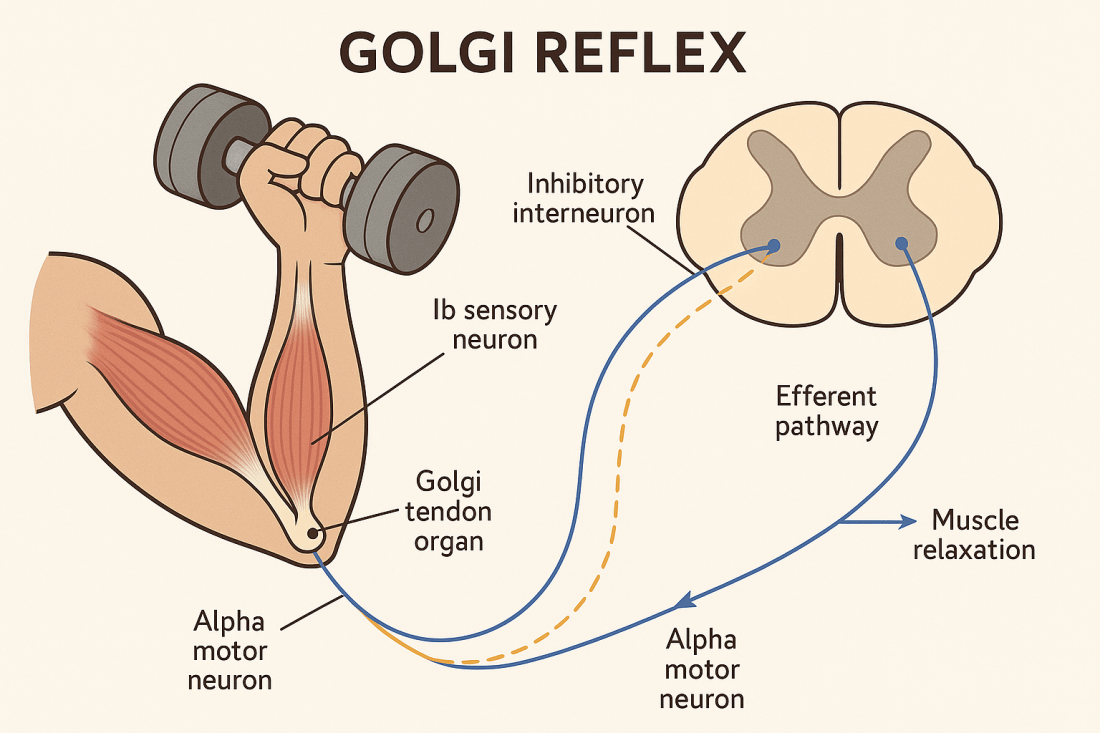

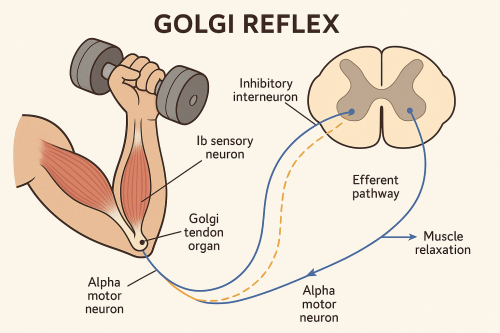

The blood vessels, seen as pathways of both Blood and Qi, rely on the Heart’s warmth and rhythm to remain supple and open. But TCM also suggests that nerve-like communication and coordination are part of the Heart’s governance.

In modern integrative interpretations:

- The autonomic nervous system (ANS), particularly the parasympathetic “rest-and-digest” functions, mirrors the Heart’s role in maintaining emotional and physical balance.

- Excess Fire may overstimulate the sympathetic nervous system, leading to agitation, insomnia, hypertension, palpitations, and anxiety.

- Deficient Heart Fire may lead to neurovegetative fatigue, poor concentration, and low vitality (Kaptchuk, 2000).

Thus, the vascular and neurological systems are harmonized through Fire’s balance affecting everything from blood pressure to mood and mental performance.

🧠 Fire Element and the Nervous System

TCM may not anatomically label the nervous system as Western medicine does, but the concepts of Shen, Yi (intellect), and Zhi (willpower) reflect cognitive and neurological activity.

In early summer:

- Shen becomes more active and outward, seeking expression, connection, and joy.

- The Du Mai (Governing Vessel) linked with the brain and spine, rises in importance, guiding mental alertness and emotional regulation.

- The Fire element’s influence supports neurotransmitter balance, sleep-wake cycles, and emotional processing.

From a modern neurobiological point of view, this aligns with the brain-heart connection:

- Heart Rate Variability (HRV), a marker of nervous system resilience, increases with parasympathetic tone, a goal of Heart-focused qigong and meditation

- Practices that balance Heart Fire can directly impact the vagus nerve, thereby stabilizing emotions and stress responses (Porges, 2011)

🩸 Extraordinary Meridians and Fire Circulation

The Eight Extraordinary Meridians function as deep energetic reservoirs, regulating circulation, constitutional energy, and emotional integration (Larre et al. (1996). In early summer, these vessels help modulate the Fire element’s rise and distribute Qi and Blood in ways that nourish the whole system.

1. Chong Mai (Penetrating Vessel)

- Sea of Blood, linked to Heart and uterus

- Balances hormonal and emotional rhythms

- When Fire is excess: anxiety, chest oppression, uterine bleeding

2. Ren Mai (Conception Vessel)

- Nourishes Yin; anchors the Heart through calming fluids

- Connects deeply to Heart-Yin and Shen stabilization

3. Du Mai (Governing Vessel)

- Axis of Yang energy; influences brain, spine, and nervous system

- Becomes overactive when Fire flares upward, causing insomnia or hyperarousal

4. Dai Mai (Belt Vessel)

- Regulates Qi flow around the waist, harmonizes rising Fire from middle and lower burners

By supporting these vessels through breathwork, meditation, herbs, and seasonal living, we can help regulate the Fire element’s effects on circulatory, emotional, and neurological functions.

🌿 Seasonal Strategies for Summer Balance

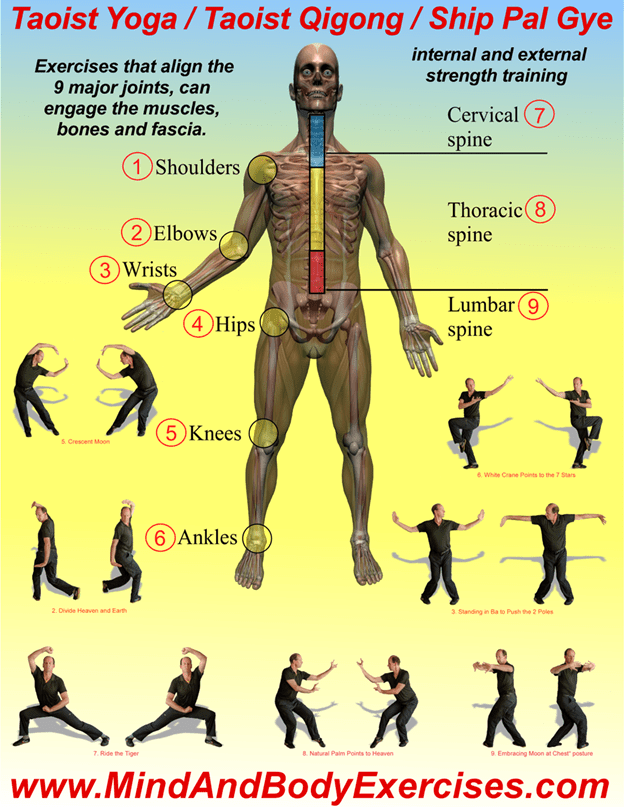

🔹 Qigong & Meditation

- Heart-centered qigong and the Inner Smile meditation bring Shen home to the Heart

- Breathing practices that lengthen the exhale can calm the nervous system and increase vagal tone

- Include “Cooling the Fire” meditations to harmonize Du Mai and Shen

🔹 Lifestyle Adjustments

- Avoid overstimulation, especially from social media, caffeine, or excess sun

- Go to bed earlier, maintain emotional equanimity

- Emphasize connection over excitement

- Prioritize joyful stillness rather than external thrill-seeking

🌀 Summary: Fire’s Intelligence in the Body

Early summer is the season of Shen and circulation, a time when the Fire element stimulates outward movement, connection, and the full flowering of human potential. Yet this power must be anchored. Overexertion, excess heat, and emotional overload can disrupt the Heart, destabilize the nervous system, and drain the blood vessels and extraordinary meridians.

Through awareness, breath, and regulation, we can cultivate a sovereign Heart, a resilient mind, and an inner flame that warms but never burns.

References:

Deadman, P., Al-Khafaji, M., & Baker, K. (2007). A Manual of Acupuncture. Journal of Chinese Medicine Publications.

Kaptchuk, T. J. (2000). The Web That Has No Weaver: Understanding Chinese Medicine (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Larre, C., de la Vallée, E., & Rochat de la Vallée, E. (1996). The Eight Extraordinary Meridians: Spirit of the Vessels. Monkey Press.

Maciocia, G. (2005). The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists (2nd ed.). Elsevier Churchill Livingstone.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.