In Korean culture, few words capture the tension between wisdom and opportunism as clearly as Cheo-se. At its most basic level, the term refers to worldly conduct, or the way one carries oneself and manages relationships within society. Yet beneath this neutral definition lies a spectrum of connotations ranging from admirable diplomacy to manipulative flattery for personal benefit (Lee, 2003).

Literal Meaning and Origins

The word Cheo-se composed of two Chinese-derived syllables:

- Cheo – “to be placed, to deal with, to handle.” It conveys the idea of one’s position or manner of responding to circumstances.

- Se – “world, age, society.” It points toward the social and historical context in which one lives.

Together, Cheo-se literally means “to handle oneself in the world” (Sohn, 2001). Traditionally, this encompassed the skills of tact, discernment, and adaptability, qualities necessary for survival and success in a hierarchical society.

The Dual Nature of Cheo-se

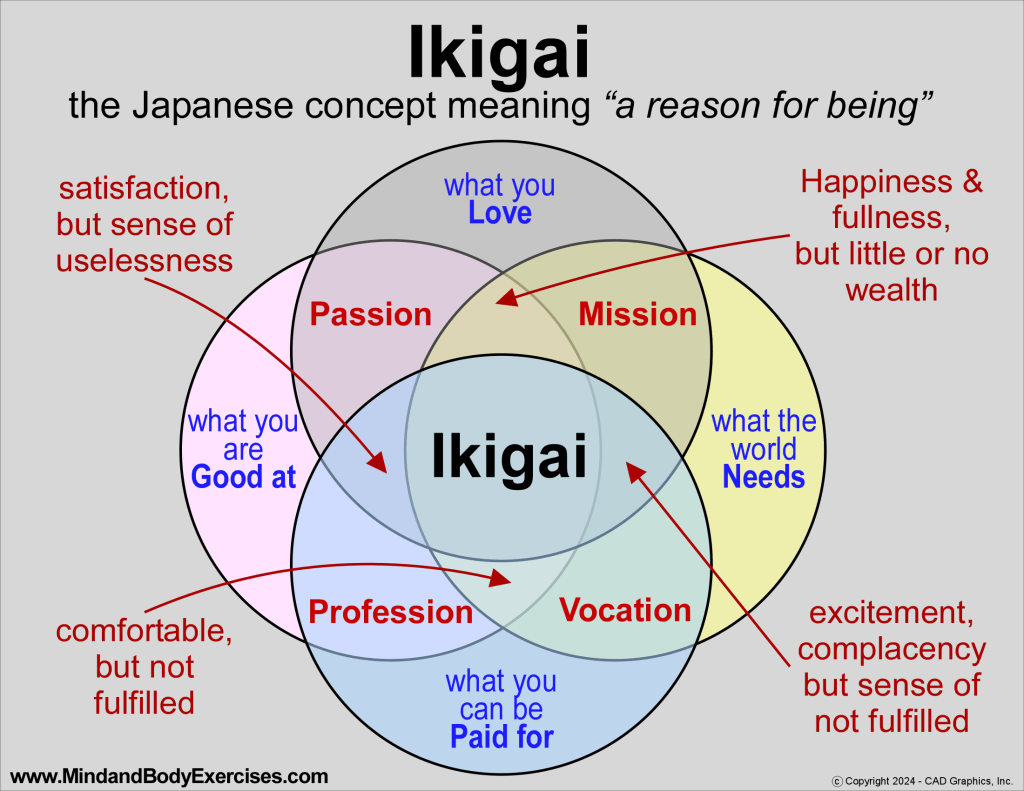

Like many cultural concepts, cheo-se is not purely positive or negative. Its interpretation depends on intention and execution:

- Positive sense: Cheo-se may describe the wisdom of diplomacy, courtesy, and adaptability. A person who practices it skillfully builds harmonious relationships, avoids unnecessary conflict, and thrives in diverse social settings. It reflects prudence and emotional intelligence.

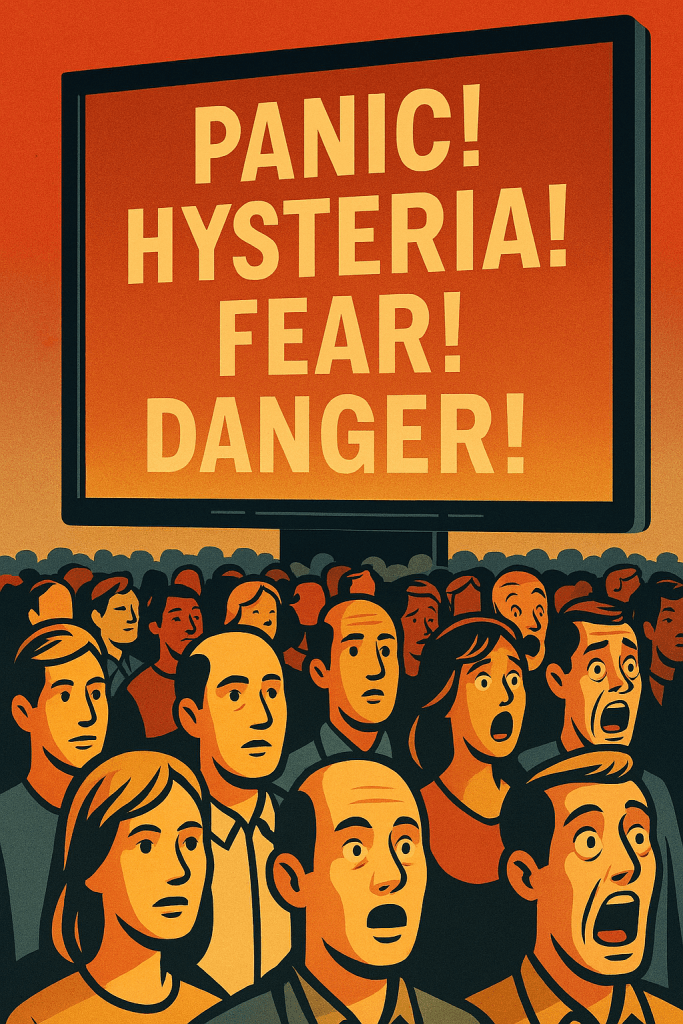

- Negative sense: At the same time, cheo-se can slide into opportunism. When “worldly conduct” is driven by ambition or self-interest, it becomes flattery, sycophancy, or manipulation. In this sense, cheo-se is akin to “knowing which way the wind blows” and adjusting behavior for personal gain, even at the cost of sincerity.

This dual nature has made cheo-se a subject of moral reflection in Korean history and literature, where figures are often judged by whether their social navigation was genuine or self-serving.

Korean proverbs warn of this danger. For example, “Sweet words may contain poison” emphasizes the risk of insincere praise. Similarly, “Words smeared on the lips” is a colloquial phrase for superficial flattery.

Cheo-se in Korean Society

Throughout Korean history, cheo-se has been shaped by Confucian values. In a system where respect for hierarchy and proper conduct were paramount, knowing how to present oneself appropriately could mean the difference between success and disgrace (Deuchler, 1992). For officials at court, scholars in examinations, or merchants in the marketplace, cheo-se was a vital skill.

In modern Korea, the term remains relevant. Navigating workplace hierarchies, academic competition, and social networks often requires an intuitive grasp of cheo-se. Compliments to a superior, careful word choice in meetings, or outward agreement with group consensus can all be forms of worldly conduct. While some see these as strategic necessities, others criticize them as shallow flattery that undermines authenticity.

Proverbs reflect this pragmatic side as well. “A word can pay back a thousand nyang debt” highlights the enormous power of speech and tact in relationships. While not inherently negative, it illustrates how skillful words, whether genuine or flattering can transform one’s fortunes.

Universal Lessons Beyond Korea

Although cheo-se is rooted in Korean language and culture, the underlying dilemma is universal. Every society wrestles with the line between:

- Healthy diplomacy that fosters harmony and cooperation, and

- Insincere flattery that erodes trust and integrity.

This concept resonates with English expressions such as “political savvy,” “social maneuvering,” or “playing the game.” In both East and West, the art of social navigation often raises the same ethical questions: How much should one adapt to the expectations of others? When does tact become manipulation? (Goffman, 1959).

A Holistic Perspective

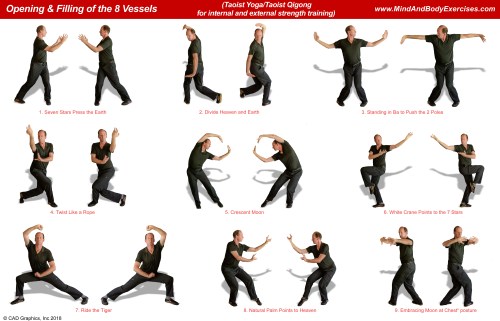

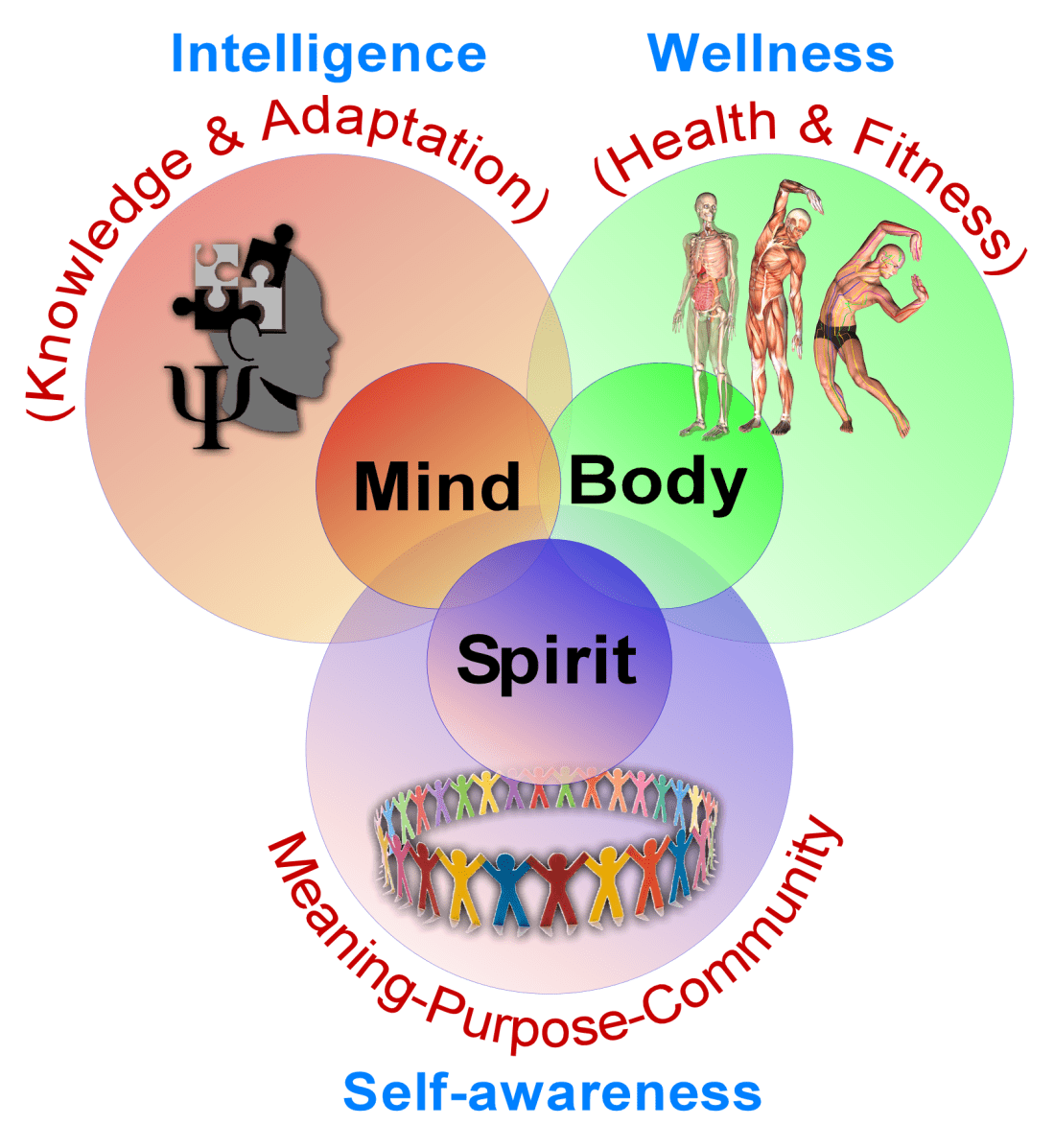

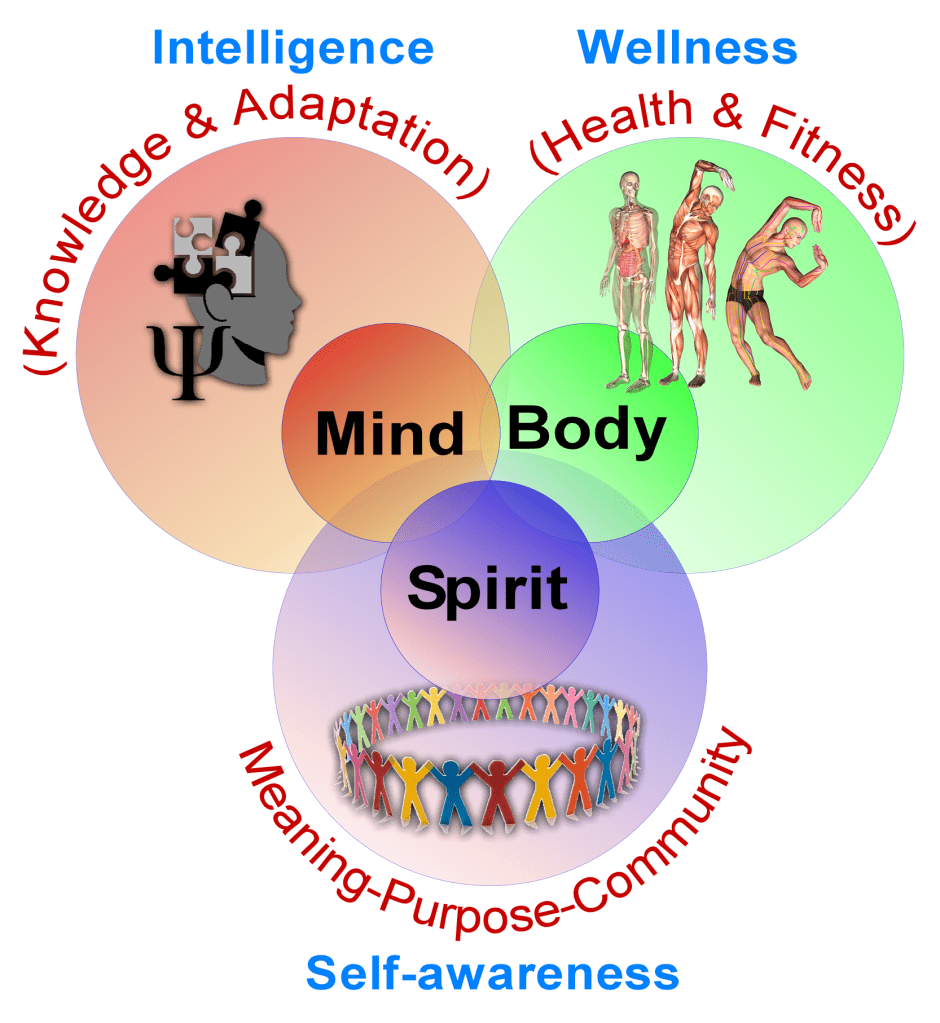

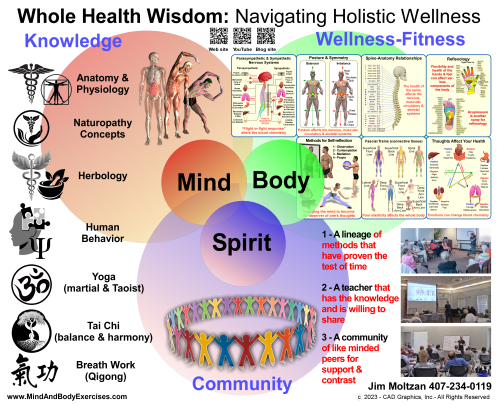

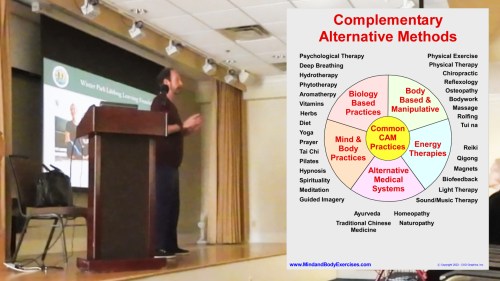

From a holistic viewpoint, balancing body, mind, and spirit – cheo-se challenges us to consider authenticity in our interactions. While adaptability and courtesy are valuable, they lose their integrity when they mask true intentions or exploit others for personal benefit. Mindfulness practice, Taoist and Confucian philosophy, and even modern psychology all suggest the same principle: genuine respect must underlie social conduct (Tu, 1985; Kabat-Zinn, 2005).

Authentic cheo-se is not about bending to every wind of circumstance but about maintaining harmony while remaining true to one’s values. It is the art of being skillful without being deceitful, diplomatic without being servile, adaptive without being opportunistic.

Conclusion

The Korean concept of cheo-se offers a rich lens for examining the balance between adaptability and authenticity in human relationships. While it can describe admirable social wisdom, it can also slip into the realm of flattery and opportunism. Reflecting on cheo-se reminds us that our conduct in the world is always a dance between outer harmony and inner integrity.

For readers seeking to navigate modern life with grace, the lesson is clear: cultivate the art of cheo-se, but let sincerity and respect guide its practice.

References:

Deuchler, M. (1992). The Confucian transformation of Korea: A study of society and ideology. Harvard University Press. https://archive.org/details/confuciantransfo0000deuc

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books.https://archive.org/details/presentationofs00goff

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. Hyperion.

Lee, P. H. (2003). Sourcebook of Korean civilization: From the seventeenth century to the modern period. Columbia University Press.

Sohn, H. M. (2001). The Korean language. Cambridge University Press.

Tu, W. M. (1985). Confucian thought: Selfhood as creative transformation. State University of New York Press.