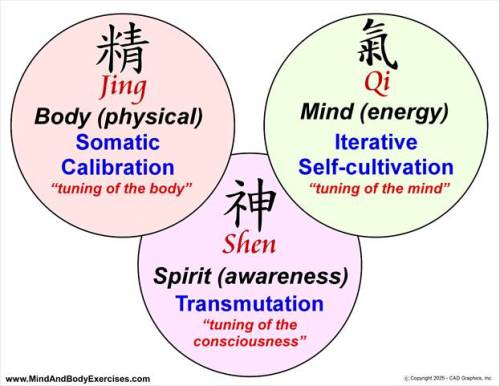

Within this framework there are 3 distinct mindsets or phases, when it comes to training and self-improvement. However, this concept can also be applied towards various other walks of life from the soldier, the martial artist, the yoga practitioner, the car mechanic, the nurse, the carpenter, the parent, among many other walks of life, and all ages, races, and orientations.

• The Warrior – focuses mostly on the physical, the body, the movement, doing the work, getting the job done, defending, protecting and in general, looking out for others. In modern society, we can find warriors in various professions that require physical and mental strength, resilience, and a proactive approach to challenges. Examples include soldiers who protect their countries, Law enforcement and firefighters who risk their lives to save others, athletes who train rigorously to excel in their sports, parents and people who advocate for the benefit of others.

• The Scholar – focuses on the history, the backstory, the mechanics, understanding how, when, where and why things work. Scholars are those who delve into knowledge, research, and the understanding of their fields. Modern examples include scientists who explore the mysteries of the universe, historians who study and interpret past events, educators who impart knowledge and foster intellectual growth in their students, leaders in the workplace who teach their employees their craft and those who are looking for answers to other issues.

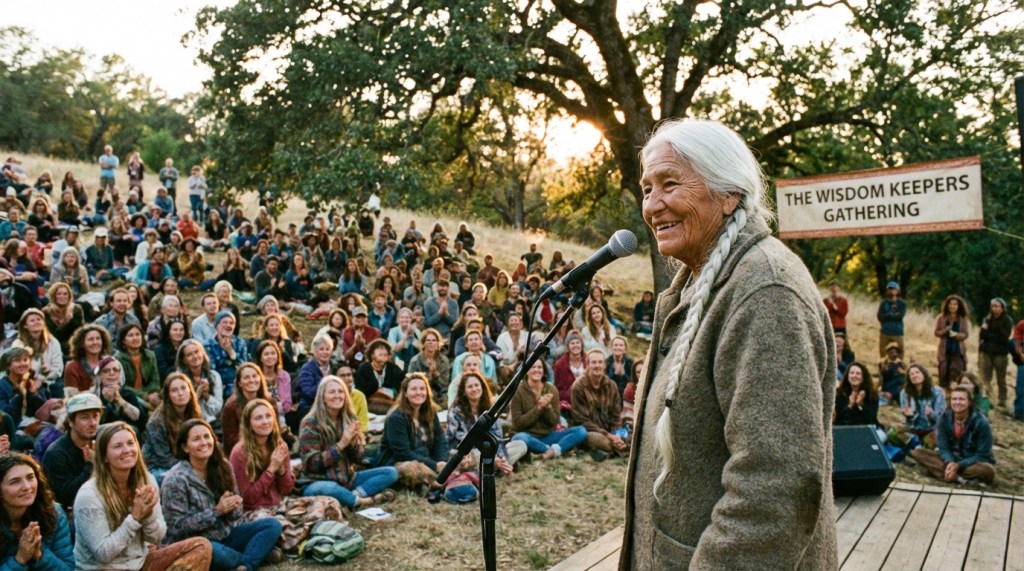

• The Sage – draws upon life experiences from being a warrior or scholar to make wise decisions. Examples in modern society include therapists who help individuals navigate their mental health journeys, mentors who provide guidance to their protégés, community leaders who use their understanding of societal dynamics to create positive change, and parents or individuals that mentor others. This list is by no means, exclusive.

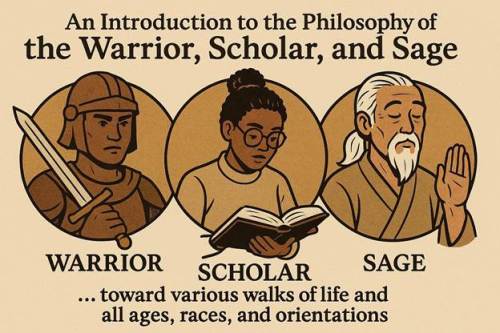

This progression reflects the Confucian path of xiushen or self-cultivation, which begins with the somatic re-calibration of the body, proceeds to the iterative cultivation of the mind, and culminates in the transmutation of higher virtue and self-awareness. A sequence mirrored in the stages of what some martial artists refer to as “Mudo training.”

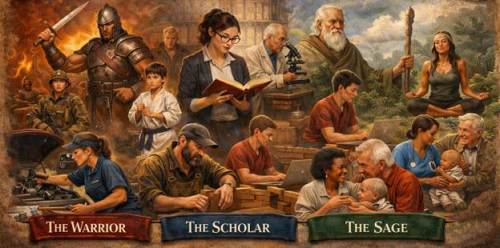

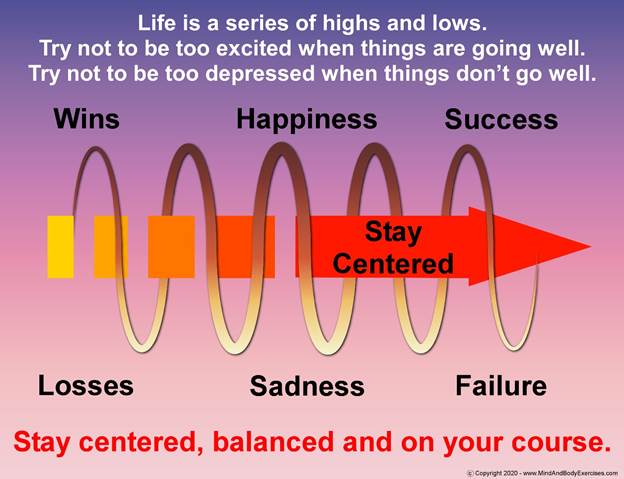

There is much relevance in this archetypal triad today. In the modern world, the martial path is often misunderstood as archaic or irrelevant, reduced to competitive sport, mere self-defense techniques or an afternoon activity for young children. Yet the deeper essence of Mudo, and its embodiment in the Warrior-Scholar-Sage archetype, remains profoundly relevant. Modern life presents its own battlefields: stress, distraction, ethical dilemmas, and existential uncertainty. Physical strength remains essential, but also critical thinking, emotional intelligence, self-awareness and spiritual depth. Who truly does not desire to have a stronger body, a sharp mind and a connection to something greater than the self?

Contemporary martial artists and holistic practitioners increasingly recognize the necessity of integrating these three dimensions. The physical discipline of martial training enhances health, vitality, and resilience; the intellectual discipline of study sharpens judgment and fosters adaptability; and the spiritual discipline of ethical reflection and self-awareness nurtures compassion and purpose. Together, these qualities form a foundation for leadership, community service, and meaningful living.

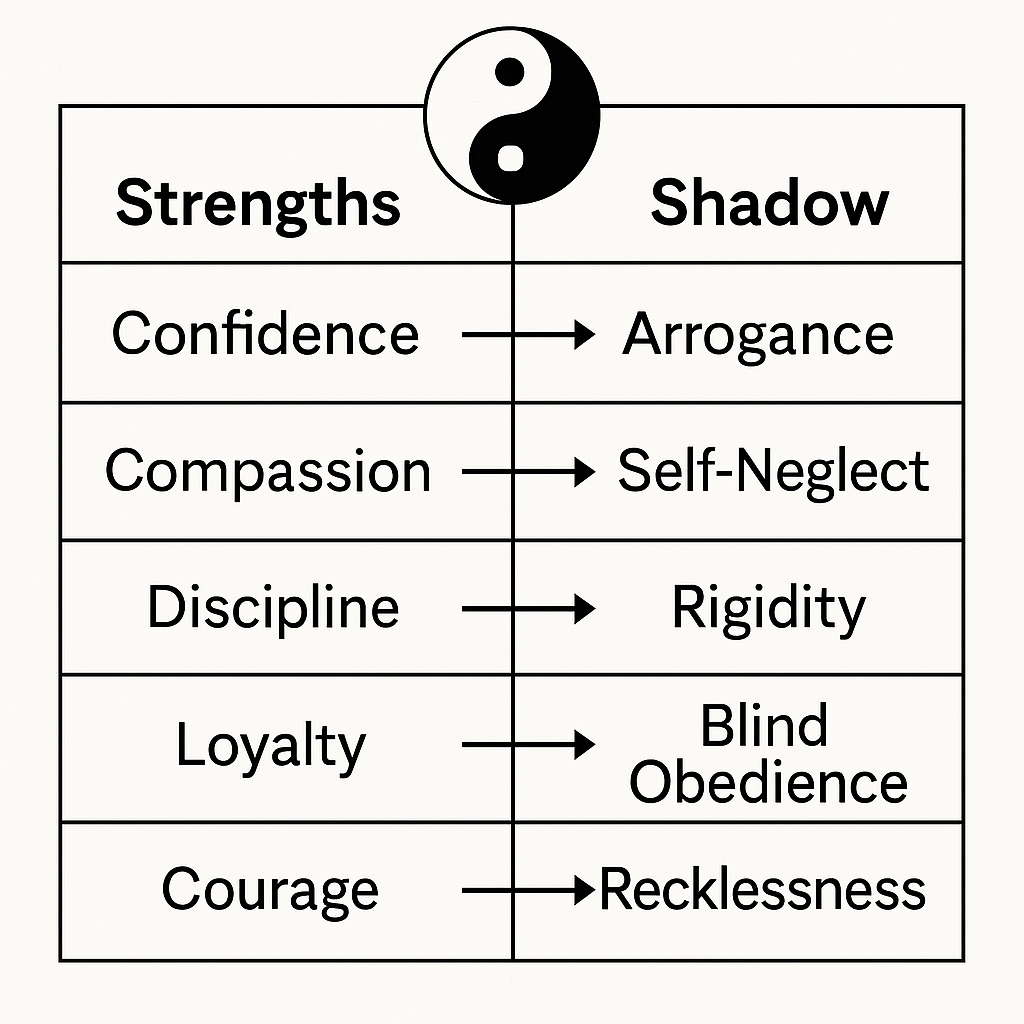

Moreover, this archetype of the Warrior, Scholar and Sage, provides a powerful framework for self-transformation. It teaches that true strength is not brute force, but disciplined action guided by wisdom; that knowledge is hollow without moral grounding; and that virtue, separated from courage and clarity, cannot manifest in the world. The individual who cultivates all three dimensions approaches the classical idea of the junzi,or the “complete human” who embodies harmony between Heaven, Earth, and humanity.

Psychologist Carl Jung referred to this as Coniunctio, describing the concept for the psychological “union of opposites” — such as conscious/unconscious or anima/animus. Similarily, psychologist Abraham Maslow’s self-actualization is the pinnacle of his hierarchy of needs, representing the innate human drive to fulfill one’s unique potential, become the best version of oneself, and find meaning, creativity, and personal growth.

A Single Path, can have Many Expressions: The apparent distinction between Mudo and the Way of the Warrior, Scholar, and Sage dissolves under closer examination. They are, in essence, two ways of describing the same holistic process of the cultivation of the body, the mind, and the spirit in pursuit of human excellence. Taoism refers to this simply as living in harmony with, the Way. Mudo is the vehicle; the Warrior, Scholar, and Sage are the milestones and manifestations along the journey.

This integrated vision has guided martial practitioners, philosophers, and sages across centuries and cultures. It remains as vital today as it was in the age of the samurai or the scholar-warrior bureaucrat. For in every era, the human being who embodies courage, wisdom, and virtue, with the warrior who can fight when necessary, the scholar who seeks truth, and the sage who acts from compassion, stand as a living expression of the Way itself.

It is usually not too difficult to see the warriors, scholars and sages all around us in our everyday lives and travels. For those seeking to cultivate self-mastery, they just need to look in the mirror to find them, in each and every one of us. Many of my later books from numbers 31-39 delve deeper into this theme of the warrior, scholar and Sage in everyday life.