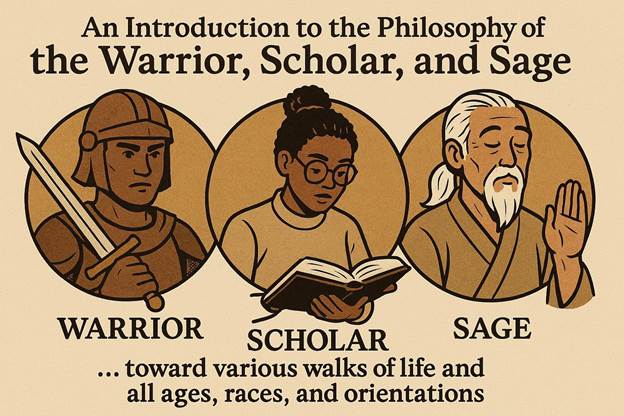

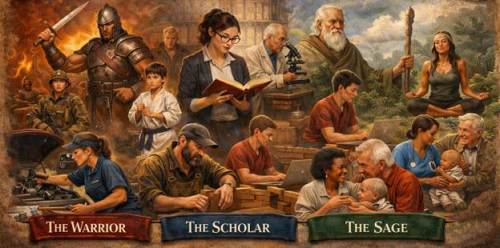

A Warrior–Scholar–Sage Perspective on Discernment, Discipline, and Rest

Modern culture equates productivity with virtue. We are conditioned to believe that constant motion is synonymous with progress and that rest is a form of weakness. Yet across classical Eastern philosophy, martial traditions, and contemplative lineages, wisdom has never been measured by how much one does, but by knowing when to act and when not to act. This discernment lies at the heart of the Warrior–Scholar–Sage archetype and is expressed through the timeless triad of True, Right, and Correct.

To live well is not merely to be busy, but to be aligned. The true path is not found through endless activity, but through refined awareness and the capacity to recognize what deserves our energy and what must be released.

The Warrior: Mastery of Discipline and Restraint

The Warrior represents Right action. Not impulsive action, not reactive behavior, but action rooted in clarity, purpose, and timing. In classical martial traditions, discipline is not merely physical conditioning but cultivated judgment. The greatest warrior is not one who fights constantly, but one who knows when not to fight.

Sun Tzu reminds us that victory is achieved not by brute force, but by superior strategy and restraint:

“He will win who knows when to fight and when not to fight.”

(The Art of War; Sun Tzu, trans. Griffith, 1971)

The Warrior’s training develops self-command, or the ability to resist distraction, ego-driven urgency, and emotional reactivity. This mastery is reflected in the modern principle of the “not-to-do list,” which removes time-wasters, unnecessary meetings, and low-impact obligations that drain vitality and clarity. Just as a martial artist conserves energy for decisive moments, the modern Warrior must learn to say “no” to what is trivial in order to say “yes” to what is meaningful.

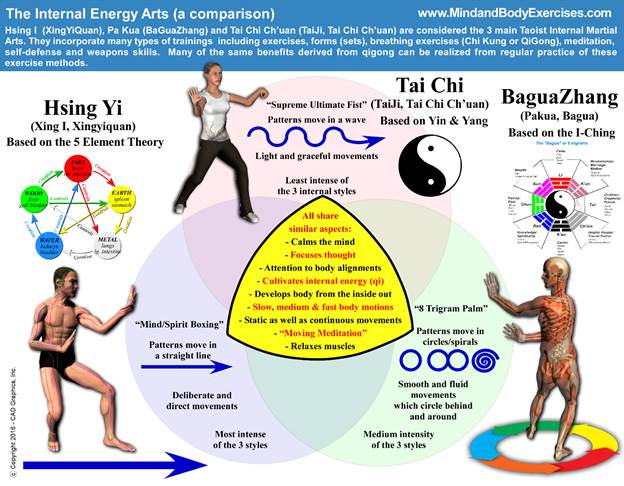

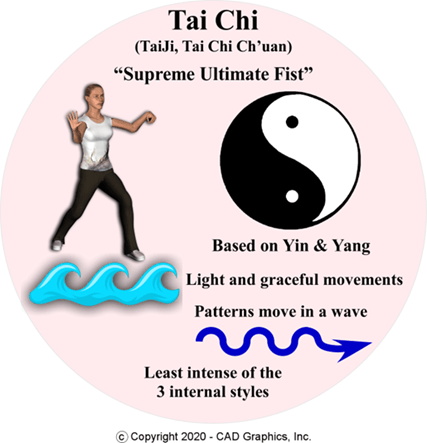

In Taoist philosophy, this principle is expressed as wu wei, or effortless action through alignment rather than force. Wu wei does not mean passivity; it means acting only when action is harmonious with circumstance (Lao Tzu, trans. Mitchell, 1988). The Warrior does not struggle against the current of life; he moves with it.

The Scholar: Clarity of Mind and Discernment of Truth

The Scholar represents True understanding. Before action, perception must come. Before movement, awareness must come. The Scholar refines cognition, attention, and reflection so that effort is guided by wisdom rather than compulsion.

In Eastern philosophy, clarity is cultivated through stillness. The Tao Te Ching teaches:

“To the mind that is still, the whole universe surrenders.”

(Lao Tzu, trans. Mitchell, 1988)

This stillness is not emptiness but receptivity. It is the mental discipline that allows one to distinguish signal from noise, value from distraction, essence from excess. The Scholar understands that perpetual stimulation fragments attention and erodes creativity. Neuroscience now confirms that insight, problem-solving, and emotional regulation depend upon cycles of focused engagement and deliberate rest (Raichle, 2015; Kaplan & Berman, 2010).

Modern productivity research echoes ancient wisdom: deep work requires boundaries. Without reflection, we confuse urgency with importance. Without rest, we confuse movement with meaning. The Scholar therefore cultivates the discipline of reflection, journaling, meditation, and contemplative study, practices that refine perception and illuminate what is true.

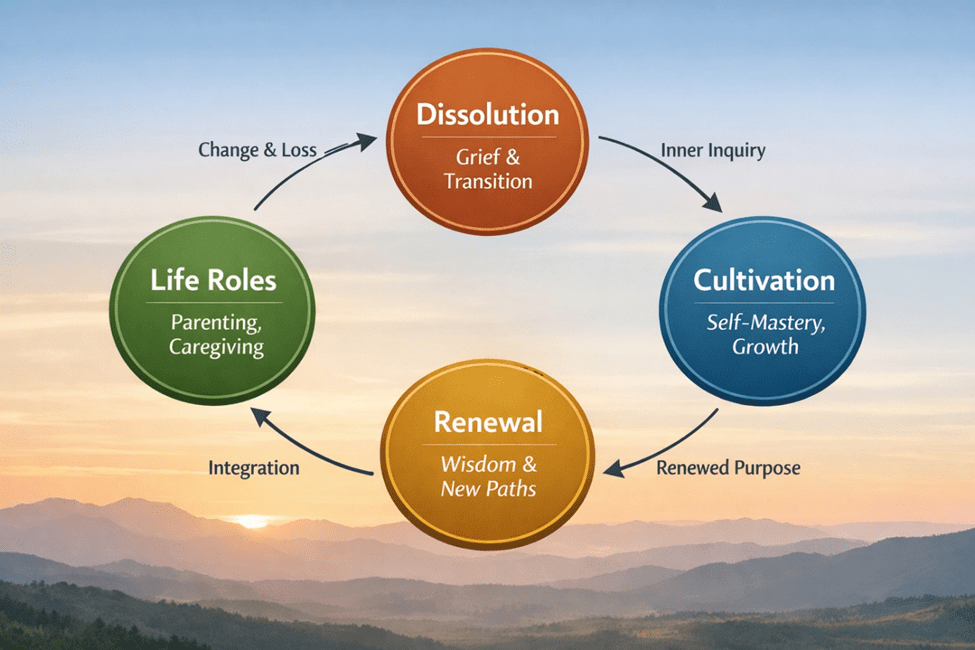

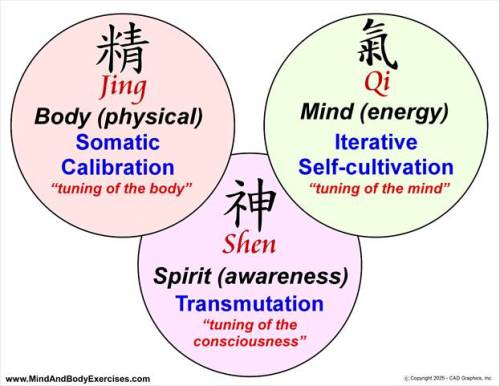

The Sage: Alignment with Natural Law

The Sage embodies what is Correct, not merely in a moral sense, but in accordance with natural rhythm and universal order. The Sage recognizes that life unfolds in cycles: effort and restoration, engagement and withdrawal, expansion and contraction.

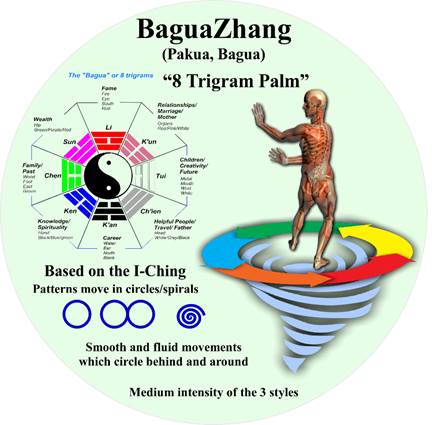

Traditional Chinese philosophy expresses this through the doctrine of yin and yang, complementary forces in perpetual transformation (Kaptchuk, 2000). Activity without rest becomes exhaustion. Rest without purpose becomes stagnation. Health, creativity, and wisdom arise from dynamic balance.

The Sage understands that overextension leads to collapse and that excessive control produces resistance. In Buddhism, this is reflected in the Middle Way, the path between indulgence and deprivation (Rahula, 1974). In Confucian ethics, it is expressed through li, proper conduct arising from situational appropriateness rather than rigid rules (Ames & Rosemont, 1998).

To the Sage, knowing when not to act is as powerful as knowing when to act. Stillness is not absence. Silence is not emptiness. Withdrawal is not retreating. These are strategic expressions of wisdom.

The Integrated Path: Living the True, Right, and Correct Life

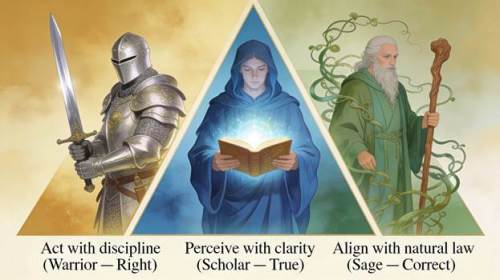

When the Warrior, Scholar, and Sage are integrated, life becomes a practice of intelligent engagement. The individual learns to:

- Act with discipline (Warrior — Right)

- Perceive with clarity (Scholar — True)

- Align with natural law (Sage — Correct)

This triadic harmony produces a life of purposeful effort rather than frantic striving. It teaches us to push forward when the moment calls for courage and endurance and to withdraw when reflection, restoration, or re-calibration is required.

The ancient sages understood what modern neuroscience now confirms: burnout is not a failure of character but a failure of rhythm. Creativity does not arise from constant stimulation but from alternating cycles of tension and release. Wisdom does not emerge from accumulation but from discernment.

To live well is not to do more. It is to do what matters and to release what does not.

The highest form of productivity is not busyness. It is alignment.

The highest form of discipline is not force. It is restraint.

And the highest form of wisdom is knowing, with clarity and courage, and when to do and when not to do.

References

Ames, R. T., & Rosemont, H. (1998). The analects of Confucius: A philosophical translation. Ballantine Books.

Griffith, S. B. (Trans.). (1971). Sun Tzu: The art of war. Oxford University Press.

Kaplan, S., & Berman, M. G. (2010). Directed attention as a common resource for executive functioning and self-regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691609356784

Kaptchuk, T. J. (2000). The web that has no weaver: Understanding Chinese medicine (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Lao Tzu. (1988). Tao Te Ching (S. Mitchell, Trans.). HarperCollins.

Rahula, W. (1974). What the Buddha taught (2nd ed.). Grove Press.

Raichle, M. E. (2015). The brain’s default mode network. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38, 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014030