The spiritual histories of Europe and Asia between the ninth and eighteenth centuries reveal both stark contrasts and surprising parallels. While the Holy Roman Empire represented a distinctly Christian civilization in Europe, Asia contained a vast spiritual mosaic shaped by Buddhism, Hinduism, Daoism, Confucianism, and emerging new traditions. Examining them side by side highlights not only their differences, but also their shared struggles with orthodoxy, reform, and the search for direct spiritual experience.

Early Medieval Period (800–1000 CE)

In Europe, the coronation of Charlemagne in 800 marked the symbolic beginning of the Holy Roman Empire, embedding Christianity as the unifying spiritual and political authority. Benedictine monasteries flourished, emphasizing discipline, prayer, and scholarship (McKitterick, 2008). Missionaries spread Christianity into Central and Northern Europe, solidifying the Church’s cultural dominance.

At the same time, Asia was undergoing significant transformations. In India, the philosopher Śaṅkara refined Advaita Vedānta, a non-dualistic vision of ultimate reality that would remain influential for centuries (Deutsch, 1988). Buddhism continued to flourish in China and Tibet, with Chan (Zen) Buddhism emphasizing meditation and direct awakening (Faure, 1993). In Japan, esoteric Buddhist schools such as Shingon and Tendai were introduced, while in Tibet royal patronage ensured Buddhism’s lasting establishment (Kapstein, 2006).

High Medieval Period (1000–1200 CE)

The Holy Roman Empire entered the high medieval period with expanding papal authority and the rise of scholastic theology. Thinkers such as Anselm of Canterbury laid the groundwork for reasoned approaches to faith (Southern, 1990). The First Crusade (1095) demonstrated the deeply spiritual yet militant expression of medieval Christianity, as the Church sought to extend its influence beyond Europe (Tyerman, 2005).

Across Asia, parallel movements of spiritual renewal were unfolding. In India, devotional currents of the Bhakti movement began to emerge, stressing heartfelt devotion over ritual and caste (Hawley, 2015). In China’s Song dynasty, Neo-Confucianism was synthesized by Zhu Xi, blending moral philosophy with metaphysics (De Bary, 1981). In Japan, Pure Land Buddhism spread among commoners, offering salvation through simple faith, while Zen Buddhism began its ascent (Suzuki, 1996). Korea’s Goryeo dynasty witnessed the maturation of Seon (Zen) Buddhism, and in Tibet, the Kagyu and Sakya schools gained structure and prestige (Samuel, 2012).

Later Medieval Period (1200–1400 CE)

By the thirteenth century, scholasticism reached its height in Europe with Thomas Aquinas, while Gothic cathedrals symbolized the union of beauty, architecture, and faith (Le Goff, 1988). Alongside official orthodoxy, Christian mystics such as Meister Eckhart and Hildegard of Bingen emphasized direct union with God, reflecting a deep hunger for personal spiritual experience (McGinn, 2006). At the same time, inquisitorial structures were established to guard orthodoxy and suppress deviation.

In Asia, spiritual life was equally dynamic. India witnessed the flowering of Bhakti poets such as Kabir, who challenged caste divisions and stressed unity with the divine (Hawley & Juergensmeyer, 1988). Chan Buddhism continued in China, alongside Daoist inner alchemy (neidan), which cultivated the transformation of essence, energy, and spirit (Robinet, 1993). In Japan’s Kamakura period, Zen influenced art, poetry, and even the martial discipline of the samurai (Addiss, 1989). Korea maintained its Buddhist culture, while Tibet received Mongol patronage that elevated the Sakya school to prominence (Kapstein, 2006).

Early Modern Period (1400–1600 CE)

Europe’s spiritual climate shifted dramatically between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Renaissance revived humanist inquiry, while the Protestant Reformation, beginning with Martin Luther’s theses in 1517, fractured Catholic unity across the Holy Roman Empire (MacCulloch, 2003). Wars of Religion ensued, and the Catholic Counter-Reformation sought to reclaim spiritual authority through renewed discipline, missionary zeal, and the Jesuit order (O’Malley, 1993).

In Asia, this same era was one of remarkable religious synthesis and renewal. In India, the Bhakti movement expanded further, and Sikhism was founded by Guru Nanak, offering a new synthesis of devotion and ethical practice (McLeod, 2009). In Ming China, Neo-Confucianism became the dominant ideology, though often blended with Buddhist and Daoist practices (Angle & Tiwald, 2017). Japan’s Zen traditions flourished in art, gardening, and tea ceremony, intermingling with Shinto rituals (Suzuki, 1996). Korea’s Joseon dynasty elevated Neo-Confucianism as state orthodoxy, though Buddhism persisted among common people (Deuchler, 1992). Tibet saw the rise of the Gelug school, and the institution of the Dalai Lama emerged as both spiritual and political authority (Samuel, 2012). Across Southeast Asia, Theravāda Buddhism spread and took firm root as the primary spiritual framework (Skilling, 2024).

Late Early Modern Period (1600–1800 CE)

In the Holy Roman Empire’s final centuries, the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) devastated Central Europe and redefined the balance between faith and politics. The Enlightenment further challenged ecclesiastical authority by placing reason and empirical science above dogma (Israel, 2001). By 1806, the Holy Roman Empire had dissolved, marking the end of a millennium of Christian-imperial identity.

Meanwhile, Asia entered an age of spiritual consolidation. In Mughal India, Emperor Akbar experimented with religious syncretism, while Sikhism solidified into a distinct faith (Eaton, 2019). In Qing China, Confucian orthodoxy reigned, but Jesuit missionaries introduced Christianity and Western science, leading to cultural exchanges and tensions (Brockey, 2007). Japan’s Edo period tightly regulated Buddhism but saw a revival of Shinto and Neo-Confucian ethics (Najita, 1987). Korea remained staunchly Confucian while underground Catholicism began to spread (Grayson, 2013). Tibet’s Gelug school solidified its control under successive Dalai Lamas, while Theravāda monasteries remained the heart of spiritual life in Southeast Asia (Skilling, 2024).

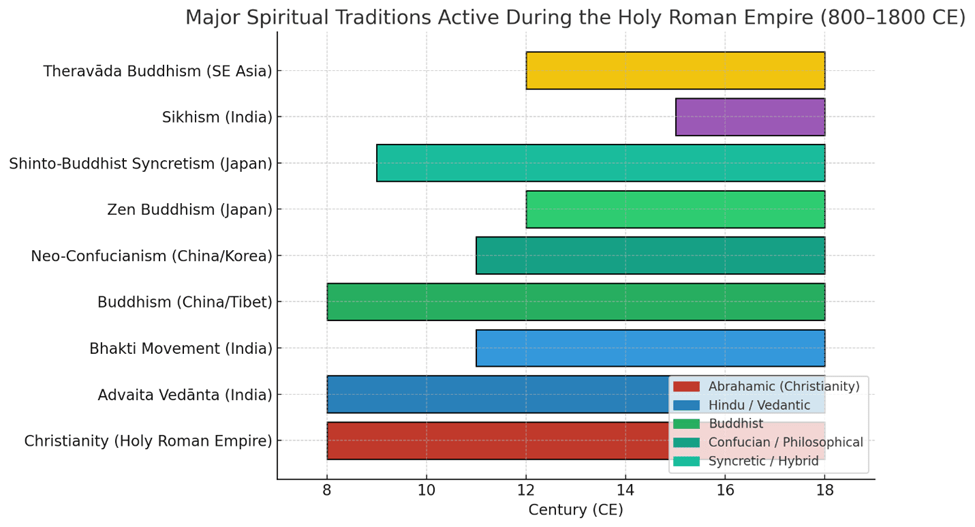

Each bar represents the approximate centuries during which each spiritual or philosophical system was prominent:

- Christianity throughout the entire Holy Roman Empire period.

- Advaita Vedānta, Buddhism, and Neo-Confucianism maintained long continuous influence.

- The Bhakti and Zen movements arose in the middle centuries.

- Sikhism appeared later in the 15th century.

- Theravāda Buddhism spread widely across Southeast Asia beginning around the 12th century.

Epilogue: Why This Historical Comparison Matters Today

Understanding the spiritual evolution of Europe and Asia between 800 and 1800 CE is not just an academic exercise; it is a mirror reflecting the origins of our modern worldviews, ethical systems, and inner struggles. The lessons drawn from these historical traditions are profoundly relevant to the 21st century in several ways.

1. Revealing the Roots of Modern Ethics and Culture

The Holy Roman Empire’s Christian moral codes and Asia’s pluralistic philosophies, Confucianism, Daoism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, remain embedded in global culture today. Western concepts of justice, duty, and conscience evolved from medieval Christian theology, while Asian societies continue to be guided by Confucian filial values and Buddhist compassion. These differing spiritual foundations still influence how nations prioritize community, governance, and moral responsibility (Wei-ming, 1996). By tracing these roots, we better understand the moral diversity that defines global civilization.

2. Recognizing Cycles of Reform and Awakening

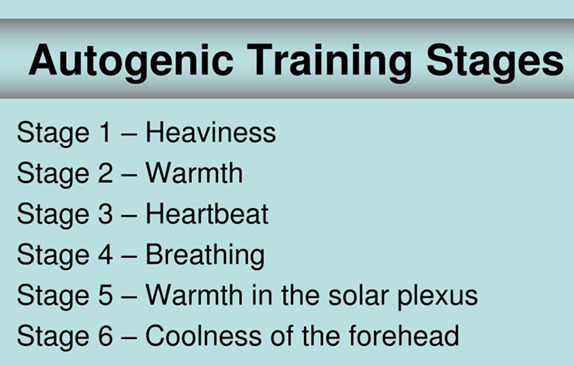

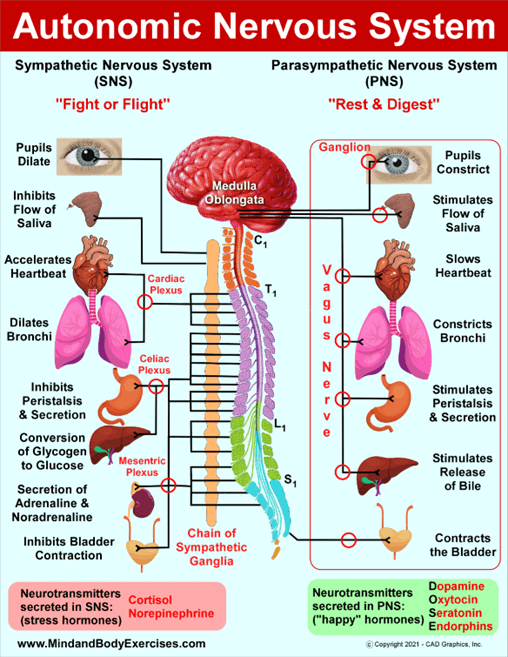

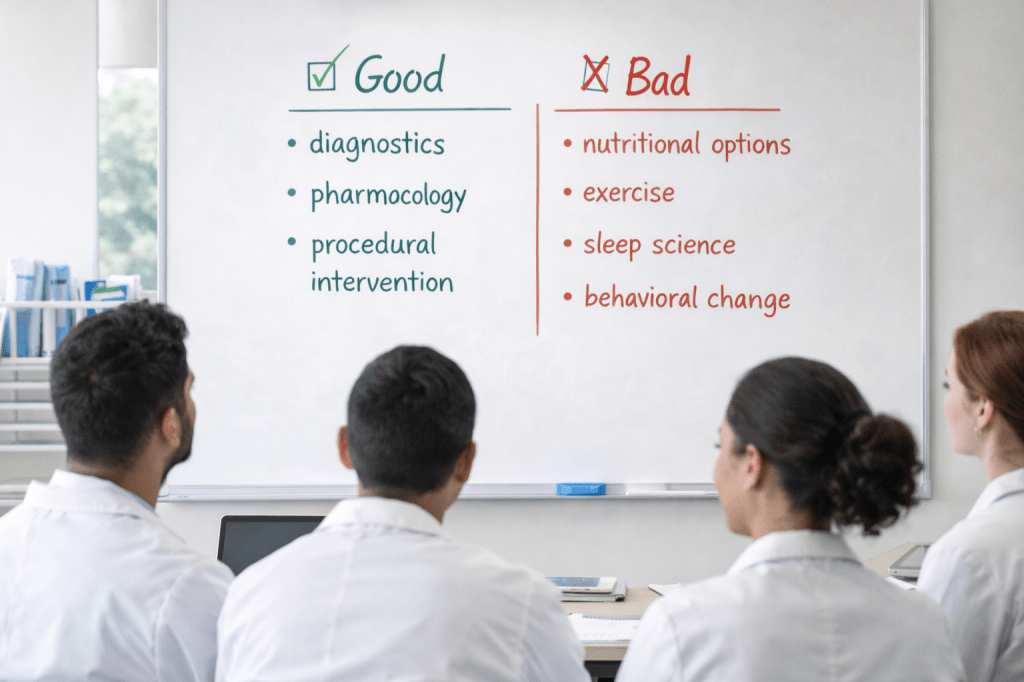

Every civilization has faced moments when inherited belief systems no longer sufficed. Europe’s Protestant Reformation and Enlightenment paralleled Asia’s Bhakti, Zen, and Neo-Confucian renewals, each reasserting inner experience over rigid dogma. In today’s world, the modern wellness movement, mindfulness training, and the integration of Eastern practices into Western medicine echo these cycles of rediscovery (Wallace, 2011). History shows that when spirituality grows stale, humanity instinctively turns inward for renewal.

3. Encouraging Cross-Cultural Understanding

Globalization has brought humanity into daily contact with belief systems that once evolved in isolation. Knowing how religions and philosophies once intersected through the Silk Road, the Jesuit missions, and early global trade, builds empathy and intercultural awareness (Said, 2001). In an era of cultural polarization, this understanding promotes tolerance and cooperation. Recognizing that different civilizations have wrestled with the same existential questions, of identity, morality, and transcendence, reminds us of our shared human story.

4. Balancing Science and Spirituality

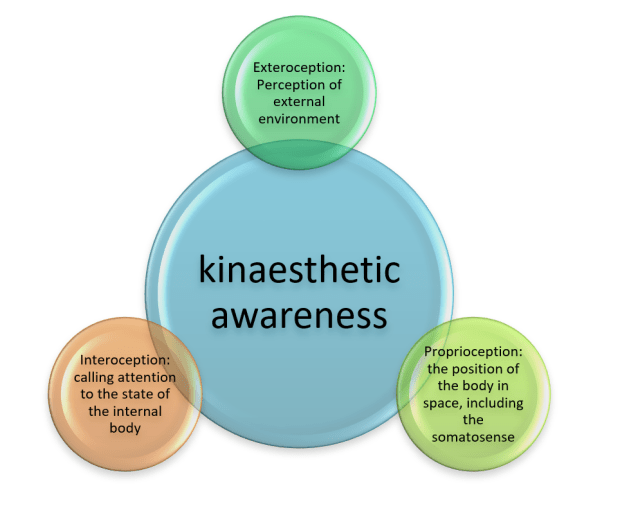

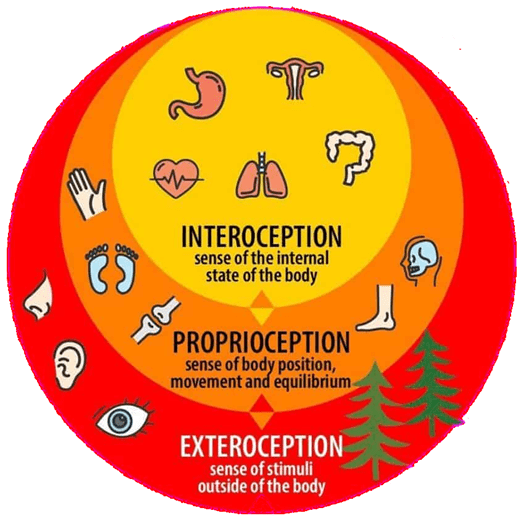

The Enlightenment’s elevation of reason and Asia’s cultivation of experiential wisdom represent complementary, not conflicting, pathways to truth. Modern neuroscience’s validation of meditation, quantum physics’ exploration of interconnectivity, and psychology’s adoption of mindfulness bridge these once-divided worlds. Revisiting their historical interplay invites a more integrated model of consciousness, one where empirical knowledge and inner experience are seen as allies in understanding human potential (Wallace, 2011).

5. Guiding Personal and Collective Transformation

From Christian mystics and Zen monks to Confucian scholars and yogic sages, these traditions emphasized transformation through discipline, awareness, and service. The same principles now inform stress reduction, leadership development, and modern psychotherapy (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). Their enduring message is that the path to mastery of body, mind, and soul, requires both inner stillness and outer effort. As in the past, growth today demands the integration of reflection with action, intellect with humility, and spirituality with practicality.

Conclusion

The parallel journeys of the Holy Roman Empire and the diverse spiritual traditions of Asia reveal the ongoing dance between order and enlightenment, faith and reason, structure and spontaneity. Both East and West pursued truth through different means, yet their destinies converged in one universal search: to refine the human being.

By studying these epochs, we rediscover not only where humanity has been but also where it might go next, a synthesis of ancient wisdom and modern understanding, offering hope for a more conscious, compassionate, and balanced future.

Europe (Holy Roman Empire) vs. Asia (800–1800 CE)

| Time Period | Europe (Holy Roman Empire) | Asia (India, China, Japan, Korea, Tibet, SE Asia) |

| 800–1000 CE | Charlemagne crowned (800); Christianity consolidated as imperial identity; Benedictine monasticism thrives; missionary expansion across Europe. | India: Advaita Vedānta refined by Śaṅkara; China: Chan (Zen) Buddhism develops; Japan: Shingon & Tendai introduced; Tibet: royal patronage of Buddhism. |

| 1000–1200 CE | Growth of papal authority; Gregorian reforms; rise of scholastic theology (Anselm); First Crusade (1095). | India: Bhakti movement emerging; China (Song): Neo-Confucianism (Zhu Xi); Japan: Pure Land & early Zen; Korea: Seon Buddhism develops; Tibet: Kagyu and Sakya schools form. |

| 1200–1400 CE | Scholasticism peaks (Aquinas); Gothic cathedrals as symbols of faith; Christian mystics (Hildegard, Eckhart); Inquisition enforces orthodoxy. | India: Bhakti poets (Kabir); China: Chan Buddhism and Daoist Neidan (alchemy); Japan (Kamakura): Zen shapes arts and samurai culture; Korea: Buddhist texts, Seon tradition strong; Tibet: Sakya dominance under Mongol patronage. |

| 1400–1600 CE | Renaissance humanism; Protestant Reformation (1517); Wars of Religion; Catholic Counter-Reformation (Jesuits, Council of Trent). | India: Bhakti expands; Sikhism founded (Guru Nanak); China (Ming): Neo-Confucian orthodoxy; Japan: Zen aesthetics (tea, gardens), Shinto-Buddhist syncretism; Korea (Joseon): Neo-Confucian state ideology; Tibet: Gelug school rises, Dalai Lama institution begins; SE Asia: Theravāda Buddhism dominant. |

| 1600–1800 CE | Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648); Enlightenment challenges Church authority; decline and dissolution of Holy Roman Empire (1806). | India: Mughal syncretism (Akbar); Sikhism consolidates; China (Qing): Confucian orthodoxy, Jesuit missions; Japan (Edo): Buddhism regulated, Neo-Confucian and Shinto revival; Korea: Confucian dominance, underground Catholicism; Tibet: Gelug Dalai Lama authority; SE Asia: Theravāda monastic centers central to society. |

References:

Addiss, S. (1989). The art of Zen: Paintings and calligraphy by Japanese monks 1600–1925. Abrams.

Angle, S., & Tiwald, J. (2017). Neo-Confucianism: A philosophical introduction. Polity Press.

Brockey, L. M. (2007). Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1pncnfv

De Bary, W. T. (1981). Neo-Confucian orthodoxy and the learning of the mind-and-heart. Columbia University Press.

Deutsch, E. (1988). Advaita Vedānta: A philosophical reconstruction. University of Hawaii Press.

Deuchler, M. (1992). The Confucian Transformation of Korea: A Study of Society and Ideology (1st ed., Vol. 36). Harvard University Asia Center. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1dnn8zj

Eaton, R. M. (2019). India in the Persianate age, 1000–1765. University of California Press.

Faure, B. (1993). Chan insights and oversights: An epistemological critique of the Chan tradition. Princeton University Press. https://archive.org/details/chaninsightsover0000faur/page/n5/mode/2up

Grayson, J. (2013). Korea – A Religious History (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1507541/korea-a-religious-history-pdf

Hawley, J. S. (2015). A storm of songs: India and the idea of the Bhakti movement. Harvard University Press.

Hawley, J. S., & Juergensmeyer, M. (1988). Songs of the saints of India. Oxford University Press. https://archive.org/details/songsofsaintsofi0000unse

Israel, J. I. (2001). Radical Enlightenment. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198206088.001.0001.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness (Rev. ed.). Bantam.

Kapstein, M. T. (2006). The Tibetans. Blackwell.

Le Goff, J. (1988). The medieval imagination. University of Chicago Press.

MacCulloch, D. (2003). The Reformation: A history. Viking.

McGinn, B. (2006). The essential writings of Christian mysticism. Modern Library.

McKitterick, R. (2008). Charlemagne: The formation of a European identity. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803314

McLeod, W. H. (2009). Sikhism. Penguin.

Najita, T. (1987). Visions of virtue in Tokugawa Japan: The Kaitokudō merchant academy of Osaka. University of Chicago Press. https://archive.org/details/visionsofvirtuei0000naji

O’malley, J. (1993) The First Jesuits. In: . Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press: 457. Loyola eCommons, Ignatian Pedagogy Books, https://ecommons.luc.edu/ignatianpedagogy_books/73

Robinet, I. (1993). Taoist meditation: The Mao-shan tradition of Great Purity. State University of New York Press.

Said, E. W. (2001). Reflections on exile and other essays. Harvard University Press. https://archive.org/details/reflectionsonexi00said

Samuel, G. (2012). Introducing Tibetan Buddhism. Routledge.

Skilling. (2024, September 25). Theravāda in history. The Open Buddhist University. https://buddhistuniversity.net/content/articles/theravada-in-history_skilling

Southern, R. W. (1990). St. Anselm: A portrait in a landscape. Cambridge University Press. https://archive.org/details/saintanselmportr0000sout

Suzuki, D. T. (1996). Zen Buddhism: Selected writings of D. T. Suzuki. Doubleday.

Wei-ming, T. (1996). Confucian Traditions in East Asian Modernity. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 50(2), 12–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3824246

Tyerman, C. (2005). God’s war: A new history of the Crusades. Harvard University Press. https://archive.org/details/godswarnewhistor00tyer

Wallace, B. A. (2011). Minding closely: The four applications of mindfulness. Snow Lion Publications. https://archive.org/details/mindingcloselyfo0000wall