From adolescence onward, many people witness the ways in which pain and suffering manifest in daily life. The young often see relatives struggle with chronic illnesses, neighbors burdened by poor health choices, and peers wrestling with emotional distress. Such early encounters plant seeds of awareness, where pain is unavoidable in the human journey, but suffering may be shaped, managed, and sometimes transformed.

The Path of Pain and Lifestyle Choices

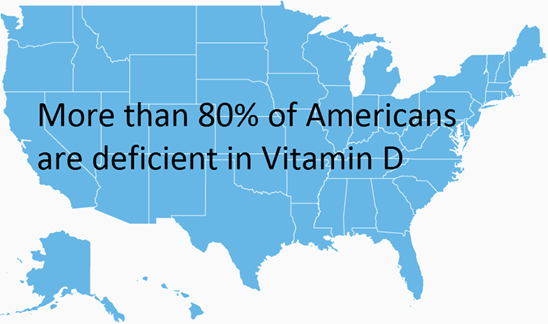

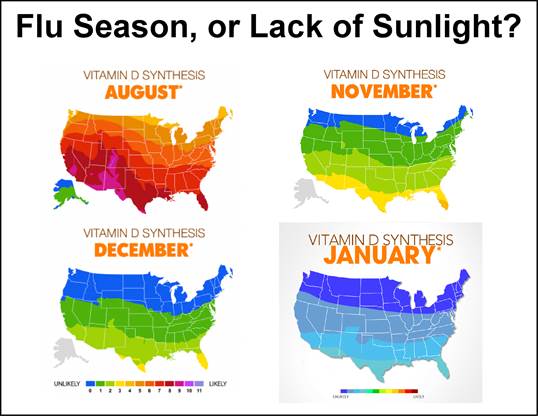

Physical pain is often the result of neglecting foundational aspects of health such as nutrition, exercise, rest, and stress management. The body, a remarkably resilient organism, also has limits. When repeatedly deprived of balanced nourishment or consistent movement, it expresses its distress in the form of aches, fatigue, or chronic illness (Gaskin & Richard, 2012).

Modern societies exacerbate this reality by promoting convenience foods, sedentary work, and overstimulation. The cumulative effects are clear in rising rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and musculoskeletal disorders. Such conditions create cycles of pain that can erode quality of life, often leading individuals to medical dependence rather than prevention. The lesson is that while pain may be unavoidable, much of it can be reduced or delayed through conscious lifestyle choices.

The Broader Dimension of Suffering

Yet suffering goes deeper than the body. Many people live with a sense of emptiness, disconnected from community and deprived of meaning. They may have food and shelter, yet suffer from emotional instability, loneliness, or lack of direction. This suffering often stems not from physical injury but from existential concerns of not knowing answers to questions of “Why am I here?” or “Does my life matter?” (Frankl, 2006).

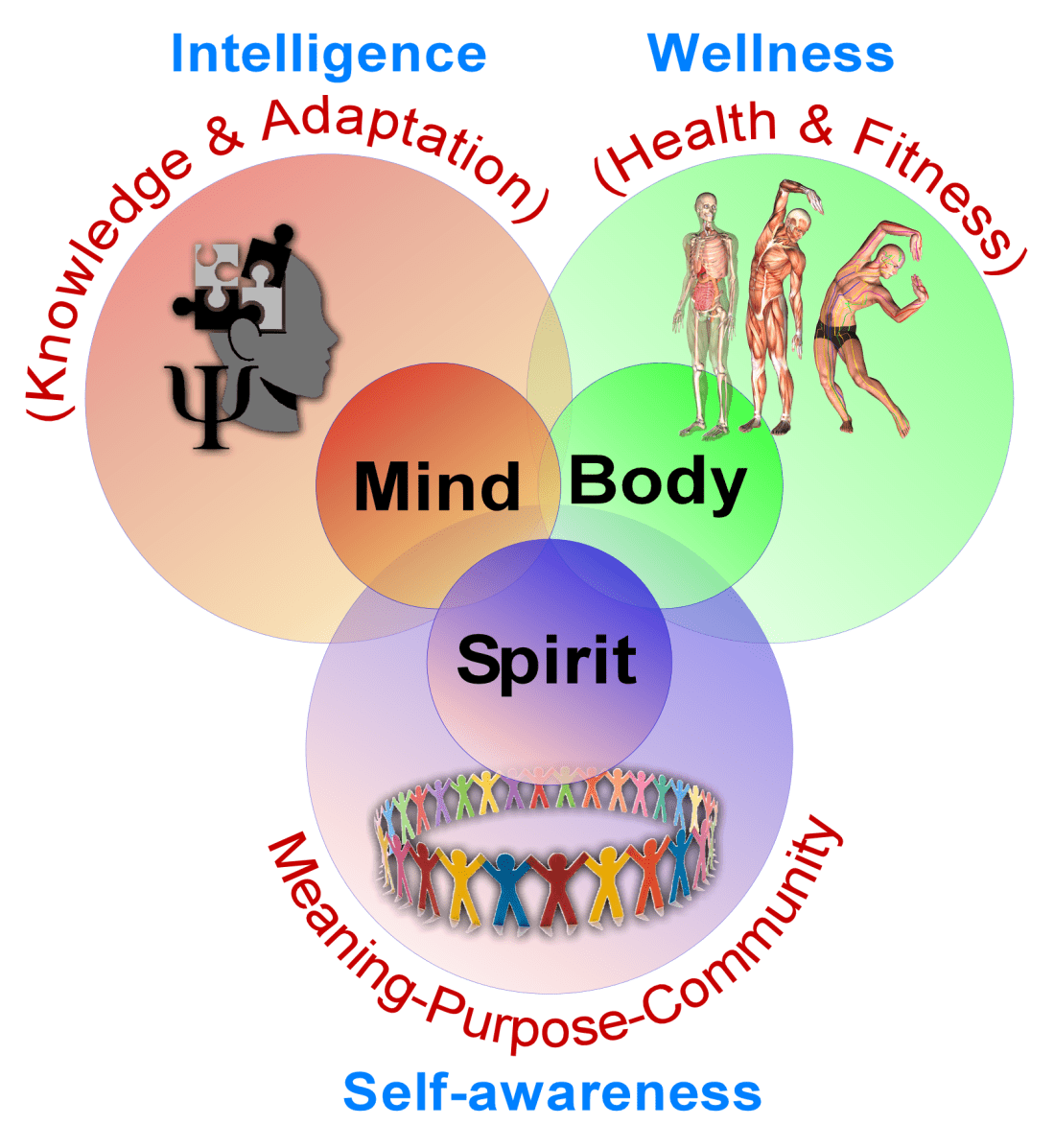

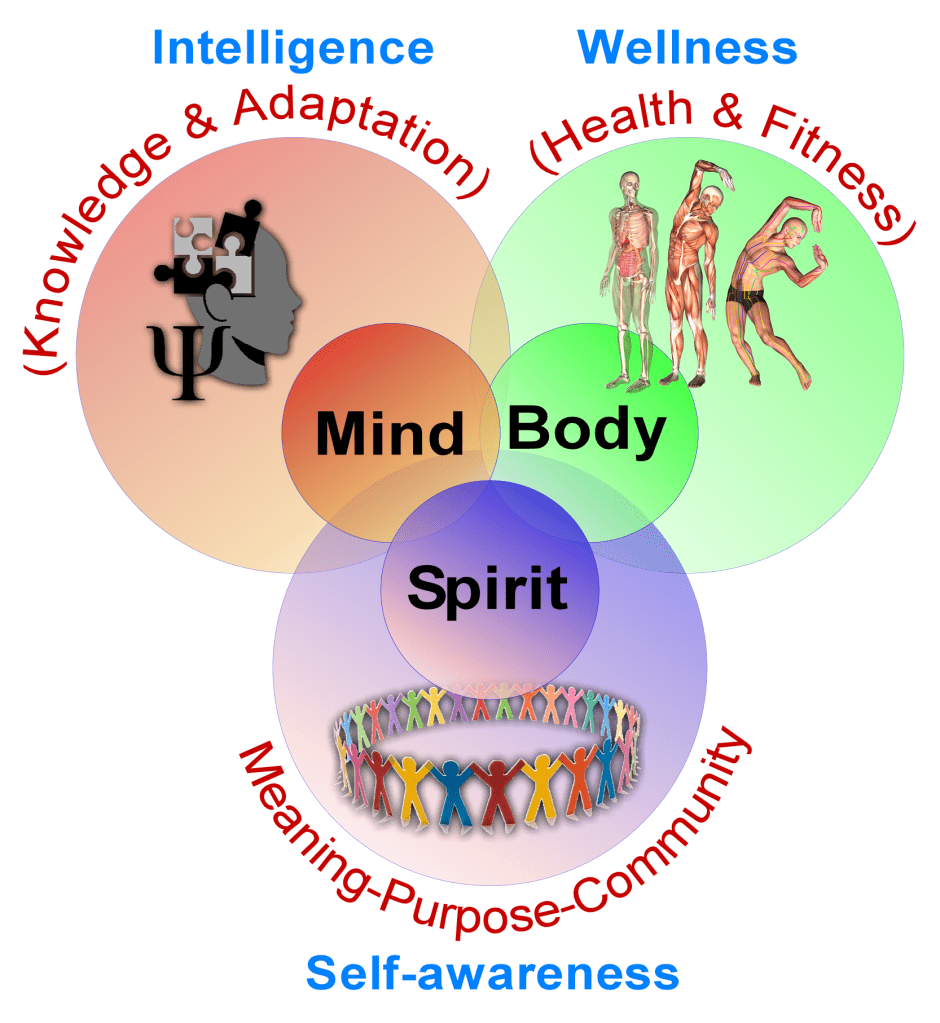

Unlike pain, which often demands medical attention, suffering requires reflection, relationships, and a search for purpose. Without these, people drift into despair, self-destructive behaviors, or emotional volatility. Such suffering demonstrates that health is not only about the body but also about the mind, relationships, and spirit.

Loneliness and the Weight of Suffering

One of the most powerful drivers of suffering is loneliness. Being socially isolated not only worsens emotional health but also amplifies physical pain by magnifying stress responses and weakening resilience (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008). Studies have shown that chronic loneliness can be as detrimental to health as smoking or obesity, leading to higher risks of depression, cardiovascular disease, and premature mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015).

Loneliness is particularly insidious because it often perpetuates itself. Those who feel isolated may withdraw further, avoiding opportunities to connect, which deepens their sense of separation. This cycle of isolation fuels suffering far beyond the body, affecting identity, hope, and self-worth.

Broken Hearts and Aging Connections

A striking example of how emotional suffering manifests in the body is “broken heart syndrome,” or stress-induced cardiomyopathy. This condition occurs when intense emotional distress, often from the loss of a spouse or loved one triggers severe, temporary heart dysfunction (Sato et al., 1990; Templin et al., 2015). The heart literally weakens under the weight of grief, illustrating the inseparable link between emotional suffering and physical health.

As people grow older, they often seek new or renewed connections to ease loneliness and sustain emotional well-being. Humans are inherently social creatures, and emotional relationships, whether with people or even pets, help fulfill this basic need. When a spouse or others that are close to us passes away or social networks shrink with age, individuals may experience profound loneliness, intensifying their suffering. In these cases, companionship becomes not a luxury but a lifeline.

Opportunities for older adults to engage in community activities, intergenerational groups, or pet companionship can reduce both emotional and physical suffering. These connections reinforce the truth that resilience and health are not maintained in isolation but in relationships.

The Shared Human Path

One universal truth is that everyone will encounter both pain and suffering. No one escapes illness, injury, or loss entirely. The recognition of this shared path can bring humility and compassion. Yet what differs among individuals is how they respond. Some choose avoidance, denial, or bitterness, while others confront pain and suffering with acceptance, resilience, and even gratitude.

The difference lies not in the inevitability of these experiences but in the interpretation of them. As Viktor Frankl (2006) observed, while suffering cannot always be avoided, it can be given meaning and through meaning, it can be endured. This insight has been confirmed in modern psychology, where resilience and purpose are linked to better coping with both pain and adversity (Ryff & Singer, 2008).

Lessons from Research and Tradition

Insights from long-term studies and cultural traditions further illuminate how pain and suffering can be softened through meaning, purpose, and connection.

The Harvard Grant Study

The Harvard Study of Adult Development, often referred to as the Grant Study, followed participants for more than 80 years initiated in 1938, making it one of the longest longitudinal studies on human well-being. Its most consistent finding was that close relationships are the strongest predictor of happiness and health, more important than wealth, social class, or even genetics (Vaillant, 2012; Waldinger & Schulz, 2010). Good relationships not only reduce emotional suffering but also protect against physical pain by lowering stress and inflammation over time.

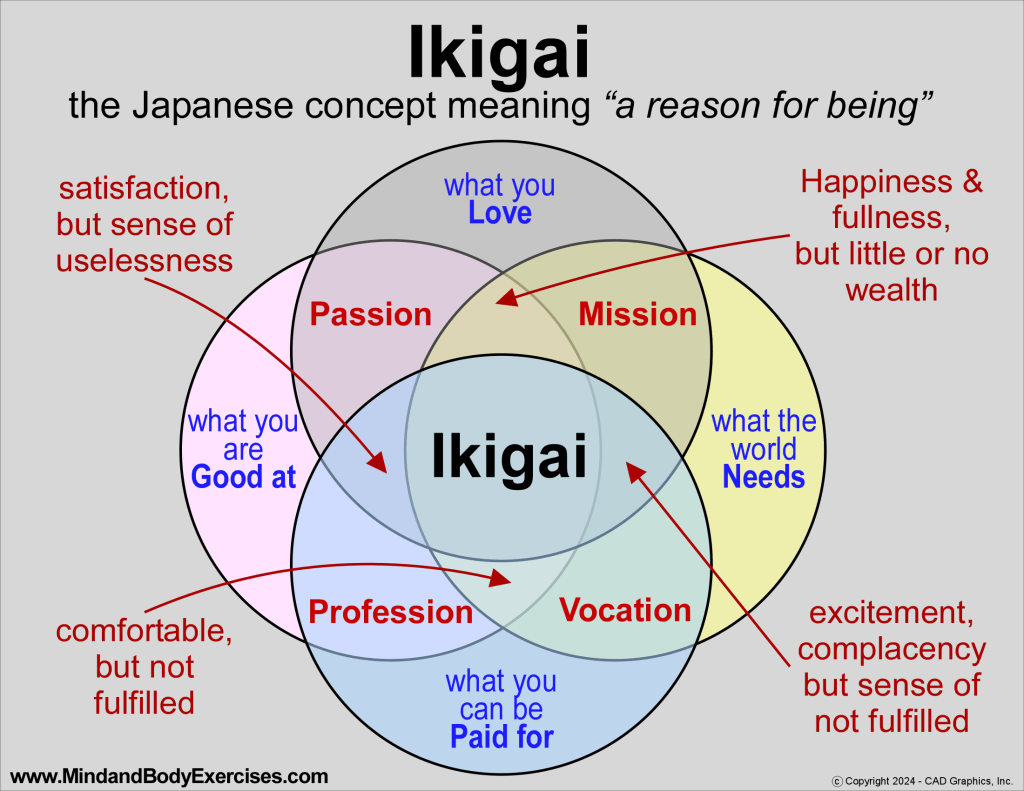

Ikigai: A Japanese Path to Meaning

In Japan, the concept of ikigai, literally translated as “a reason for being,” captures the balance of what one loves, what one is good at, what the world needs, and what one can contribute to. Ikigai provides a framework for resilience by encouraging individuals to align their daily lives with purpose and community (García & Miralles, 2017). Those who cultivate ikigai often report lower levels of existential suffering and higher life satisfaction, even in the face of aging and physical decline.

Blue Zones and Longevity

Research into the world’s “Blue Zones” or regions where people live significantly longer than average, reveals strikingly similar themes. Whether in Okinawa (Japan), Sardinia (Italy), or Nicoya (Costa Rica), communities with the greatest longevity consistently share features such as strong social ties, daily movement, plant-rich diets, and clear purpose in life (Buettner, 2012). These factors not only extend lifespan but also reduce suffering by integrating meaning, belonging, and resilience into everyday living.

Together, these insights affirm that pain and suffering are not best addressed in isolation. Instead, they are mitigated by community, purpose, and the daily practices of gratitude and connection that strengthen resilience over a lifetime.

Epilogue: Gratitude and Encounters That Shape Us

Life is short, and its brevity underscores the importance of gratitude. To practice gratitude is to recognize the gifts already present, in our love, our friends, our memories, our knowledge, and hopefully our wisdom. Gratitude does not deny pain or suffering, but rather it balances them by highlighting what is still good and enduring.

Along the way, we meet people who, whether for a moment, a year, or a lifetime, shape our paths. Sometimes these encounters steer us in new directions, open our hearts to deeper compassion, or recalibrate our perspectives. Influence is not measured by duration but by depth. Each interaction becomes part of the mosaic of our lives, enriching our journey with meaning.

In this sense, gratitude and human connection soften suffering. They remind us that while pain is unavoidable, we need not endure it in isolation or despair. By appreciating what we have and valuing the people who cross our paths, we transform life’s hardships into opportunities for growth and renewal. What might seem fleeting in time can, in fact, echo across a lifetime as a source of guidance and strength.

A Call to Action: Choosing Connection and Meaning

The challenge before us is clear. Pain will touch every life, and suffering will knock on every door. Yet within that reality lies our freedom to choose how we respond. Each of us has the capacity to soften suffering, both in ourselves and in others, by building healthier habits, nurturing relationships, and seeking meaning in everyday life.

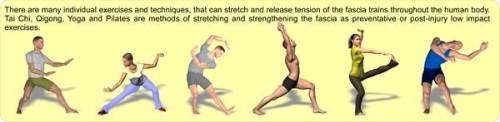

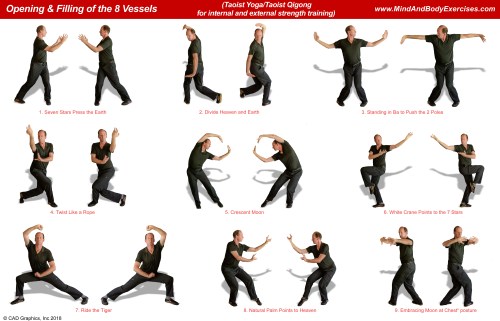

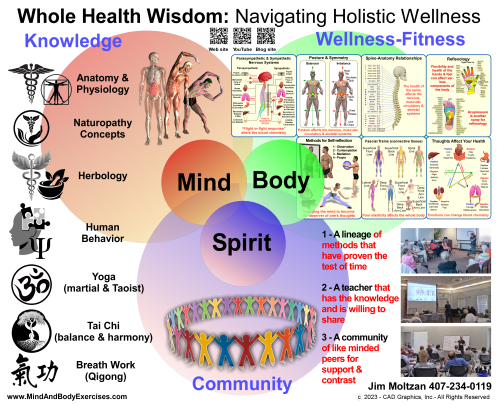

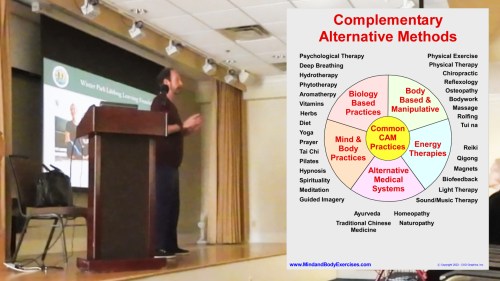

Take time to care for your body through movement, rest, and nourishment. Cultivate your mind through learning, reflection, and discipline. Strengthen your spirit by practicing gratitude and living with purpose. Most importantly, reach out to others, because connection is the antidote to isolation. Join a group, call a friend, volunteer, or simply open your heart to a neighbor.

If we each commit to these small but powerful choices, we not only transform our own experience of pain and suffering, but we also create ripples of compassion and resilience that extend into our families, communities, and beyond.

The gift of living is not just to endure but to grow, connect, and share. The time to begin is today.

References:

Buettner, D. (2012). The blue zones: 9 lessons for living longer from the people who’ve lived the longest. National Geographic Books.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. W. W. Norton & Company.

Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press. https://antilogicalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/mans-search-for-meaning.pdf

García, H., & Miralles, F. (2017). Ikigai: The Japanese secret to a long and happy life. Penguin Books.

Gaskin, D. J., & Richard, P. (2012). The economic costs of pain in the United States. Journal of Pain, 13(8), 715–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

Sato, H., Tateishi, H., Uchida, T., Dote, K., & Ishihara, M. (1990). Takotsubo-type cardiomyopathy due to multivessel spasm. Clinical Aspect of Myocardial Injury: From Ischemia to Heart Failure, 56, 56–64.

Templin, C., Ghadri, J. R., Diekmann, J., Napp, L. C., Bataiosu, D. R., Jaguszewski, M., … & Lüscher, T. F. (2015). Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (broken heart) syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(10), 929–938. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1406761

Vaillant, G. E. (2012). Triumphs of experience: The men of the Harvard Grant Study. Belknap Press.

Waldinger, R. J., & Schulz, M. S. (2010). What’s love got to do with it? Social functioning, perceived health, and daily happiness in married octogenarians. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 422–431. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019087