In a world of overflowing inboxes, closets packed with clothes, and hundreds of digital “friends,” we’re constantly inundated with choices and connections. Yet, nature may have already set a quiet boundary, or a cognitive threshold that defines just how much we can meaningfully manage. This idea is known as Dunbar’s Number.

Originally developed to explain the limit of human relationships, Dunbar’s Number now resonates far beyond sociology. It hints at a broader pattern of mental ecology, a natural balance point between meaningful engagement and cognitive overload.

What Is Dunbar’s Number?

British anthropologist Robin Dunbar proposed that humans can maintain stable, meaningful social relationships with about 150 people. This number is based on research into primate brain size and social group complexity, specifically linking the size of the neocortex to the number of relationships a species can manage (Dunbar, 1992).

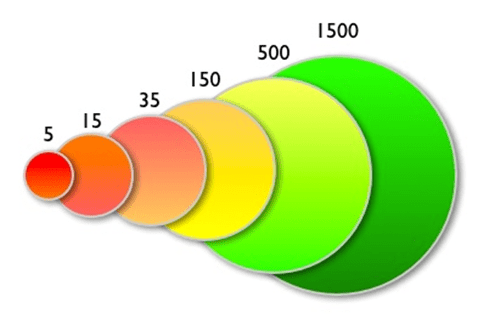

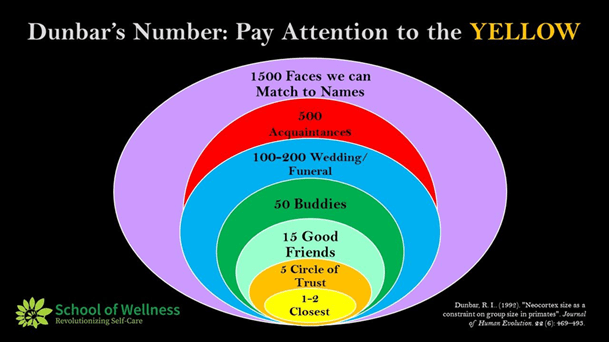

But the “150” isn’t a flat figure, but it represents the outer ring of a series of concentric social layers, each one decreasing in emotional intensity and time investment.

Dunbar’s Social Circles

- 5 Close Confidants (e.g., family, best friends)

- 15 Good Friends

- 50 Close Acquaintances

- 150 Meaningful Contacts

- 500 Acquaintances

- 1500 Recognizable Faces/Names

This layered model reflects the time and emotional energy required to maintain different levels of connection. And it turns out, it’s not just friendships that have limits.

The Broader Pattern: Where Else Does “150” Show Up?

Though Dunbar’s Number is specific to social cognition, the underlying idea that the brain can only handle so much complexity before performance drops, can be seen in many areas of life. Here are some real-world examples where a “Dunbar-like” limit seems to apply:

Short-Term Memory

Classic psychology research (Miller, 1956) suggests that we can hold 7±2 items in our short-term memory at once. While this number is much smaller than Dunbar’s 150, it reflects the same principle: our mental bandwidth is limited. Just as we can’t juggle endless thoughts, we also can’t nurture unlimited relationships.

Clothing and Possessions

Ever feel like you can’t find anything to wear, even with a full closet? That may be your cognitive load talking. While not exact science, many people report that having around 100–150 clothing items is the sweet spot where they still remember what they own, how to pair items, and what each piece is for.

Beyond that, possessions blur into mental background noise, ust like Facebook “friends” you haven’t spoken to in years.

Workplace Cohesion

Studies suggest that corporate teams function best when kept to 150 people or fewer. Beyond that, communication suffers, silos form, and social trust deteriorates. This principle has influenced everything from military units to organizational design (Hill & Dunbar, 2003).

Personal Library or Interests

You might own thousands of books or have tabs open on dozens of topics. But chances are, you can only actively track and revisit around 100–150 meaningful subjects, books, or areas of ongoing interest. This is where attention, memory, and emotional investment overlap.

Digital Files and Faces

Just like your closet, your desktop or phone storage may hold thousands of files. But in practice, people report that only a few hundred are accessed regularly, and even fewer are remembered without searching. Similarly, the number of recognizable faces we can recall is around, you guessed it is about 1500.

From Brain to Behavior: A Holistic View

So, what does all this mean for those of us pursuing a more mindful, intentional life?

Dunbar’s Number reminds us that less is often more. Whether it’s relationships, wardrobe items, digital clutter, or intellectual pursuits, our well-being depends not on volume, but on depth and manageability. We are not machines for connections. We are human beings wired for meaningful engagement.

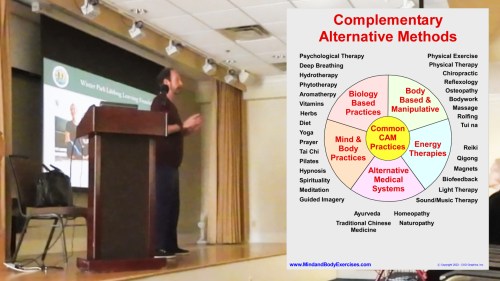

From a holistic health perspective, this understanding is vital. Emotional burnout, digital fatigue, and decision paralysis are symptoms of cognitive overload. By curating our social circles, reducing unnecessary possessions, and aligning our mental inputs with our natural limits, we create room for clarity, creativity, and calm.

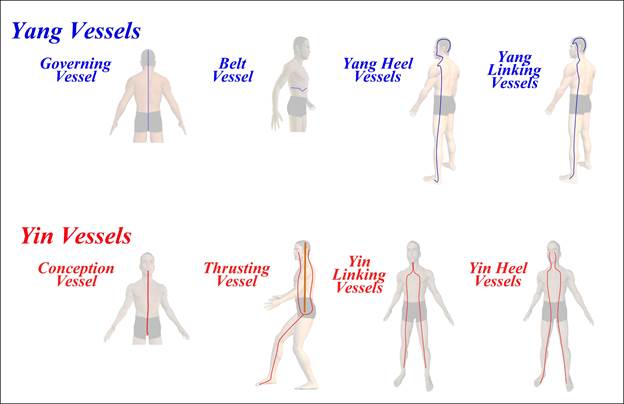

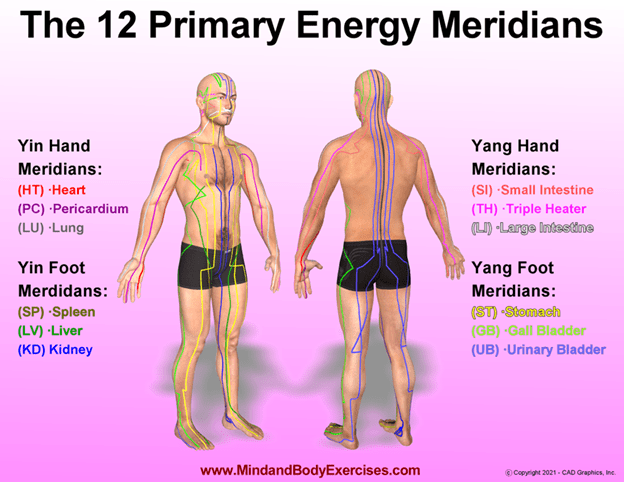

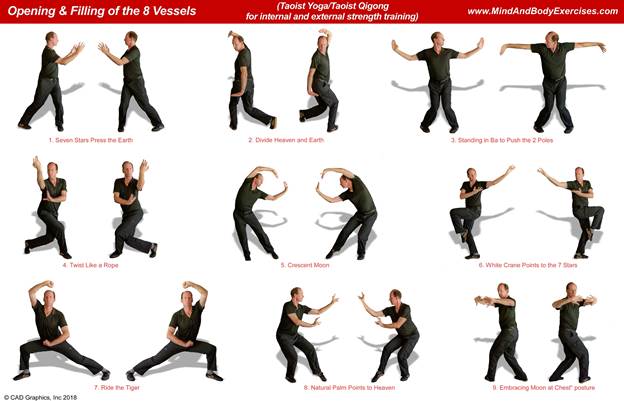

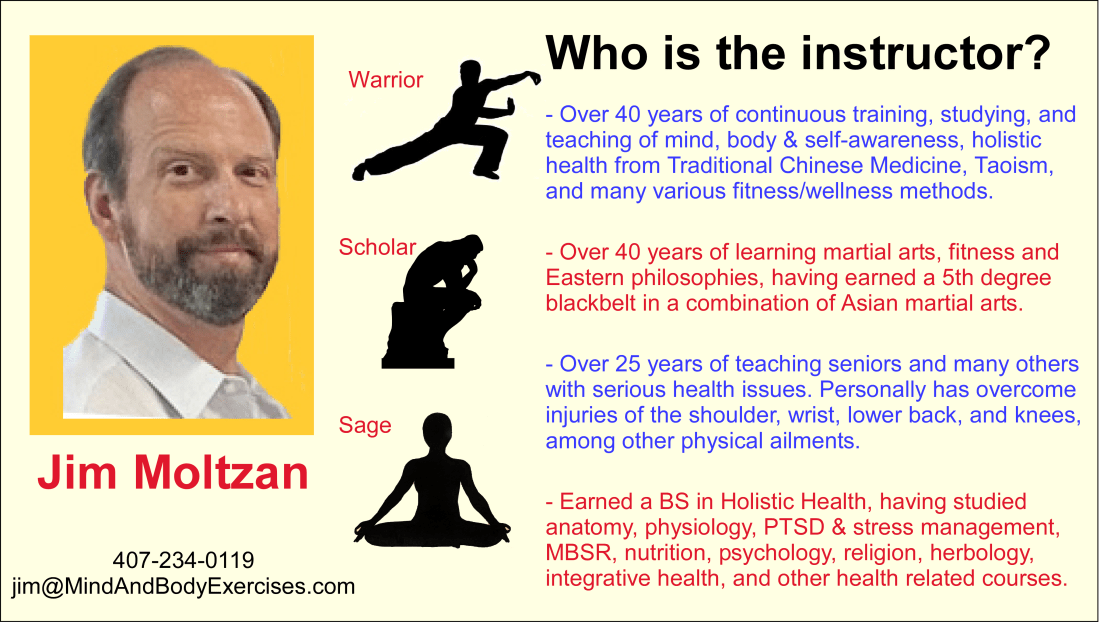

Just as Taoist teachings advise finding balance in the flow of yin and yang, Dunbar’s insights offer a secular mirror: balance in our connections, in our commitments, and in our consumption.

Final Reflection: Mental Ecology in a Noisy World

We live in a culture that celebrates more. More contacts, more options, more everything. But Dunbar’s Number challenges that notion, whispering a quieter wisdom:

“You are not meant to carry the weight of the world. Just the weight of what matters.”

Knowing your personal thresholds, whether it’s 5 close friends or 150 articles you truly care about, allows you to reclaim agency over your attention and emotional energy. In a way, this is not just science. It’s spiritual clarity.

References:

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(92)90081-J

Dunbar, R. I. M. (2018). The anatomy of friendship. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(1), 32–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.10.004

Hill, R. A., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2003). Social network size in humans. Human Nature, 14(1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-003-1016-y

Miller, G. A., Jr. & Harvard University. (1956). The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing Information. In Psychological Review (Vols. 63–97) [Journal-article]. https://labs.la.utexas.edu/gilden/files/2016/04/MagicNumberSeven-Miller1956.pdf

O’Grady, E. (2019, September 5). Who are the 5 People you Spend the Most Time With? Revolutionizing Self-Care. https://eileenogrady.com/who-are-the-5-people-you-spend-the-most-time-with/