Their Role in Holistic Health and Wellness

Holistic health emphasizes the integration of mind, body, and spirit. Within this framework, the ways in which we think about our thoughts and talk to ourselves internally play a central role in overall well-being. Two important but distinct psychological constructs, metacognition and the inner dialogue, form the foundation of self-awareness and self-regulation. While inner dialogue reflects the ongoing commentary of the mind, metacognition is the reflective process that evaluates and guides those thoughts. Understanding the distinction and interplay between the two provides powerful insight into mental, physical, and spiritual health.

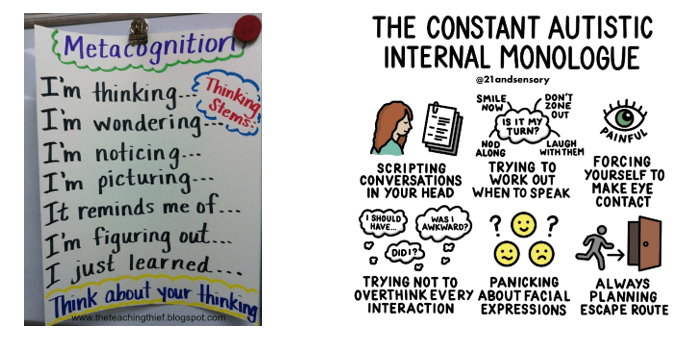

Defining Metacognition

Metacognition, often described as “thinking about thinking,” refers to the awareness and regulation of one’s cognitive processes (Flavell, 1979). It includes both:

- Metacognitive knowledge: recognizing one’s strengths, weaknesses, and strategies for thinking and learning.

- Metacognitive regulation: the ability to plan, monitor, and adapt thought patterns and behaviors to reach goals (Schraw & Dennison, 1994).

For example, when someone recognizes they are struggling to focus and decides to change their study method or environment, they are applying metacognition. It functions as a higher-order system of self-observation, enabling intentional choices rather than automatic reactions.

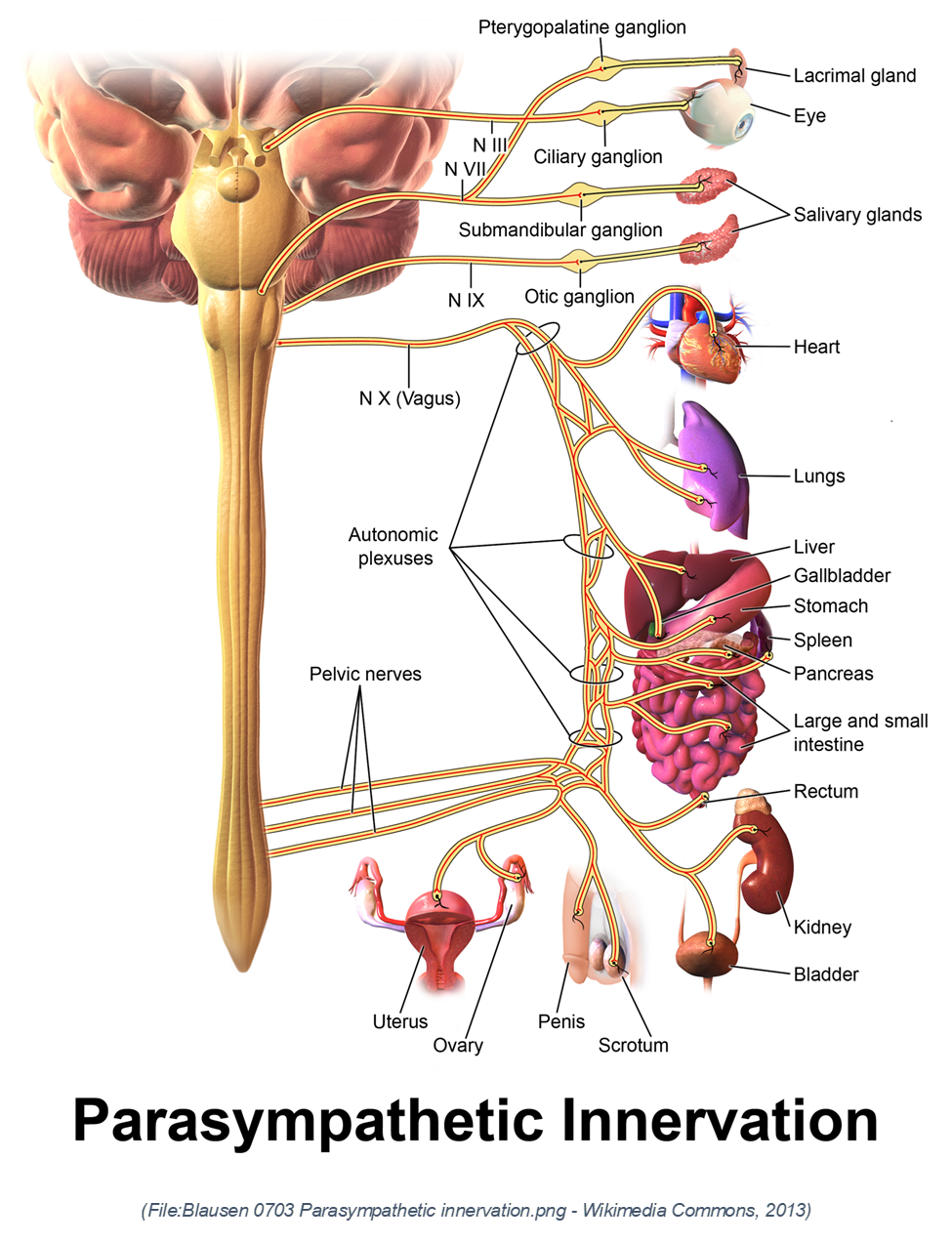

Understanding the Inner Dialogue

The inner dialogue, also known as self-talk or inner speech, represents the continuous stream of words and judgments we silently direct toward ourselves. This internal commentary can be supportive (“I am capable of handling this challenge”) or critical (“I’ll never succeed at this”) (Morin, 2009). Unlike metacognition, which is strategic and reflective, inner dialogue is often spontaneous, shaped by prior experiences, beliefs, and emotional states (Beck, 2011).

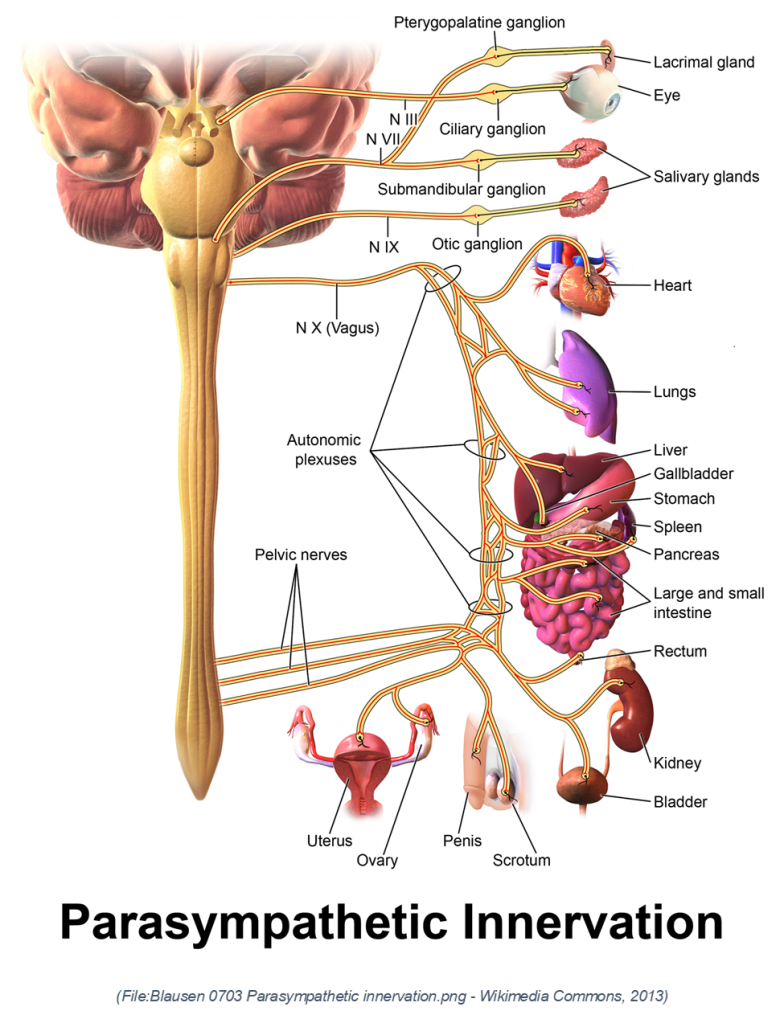

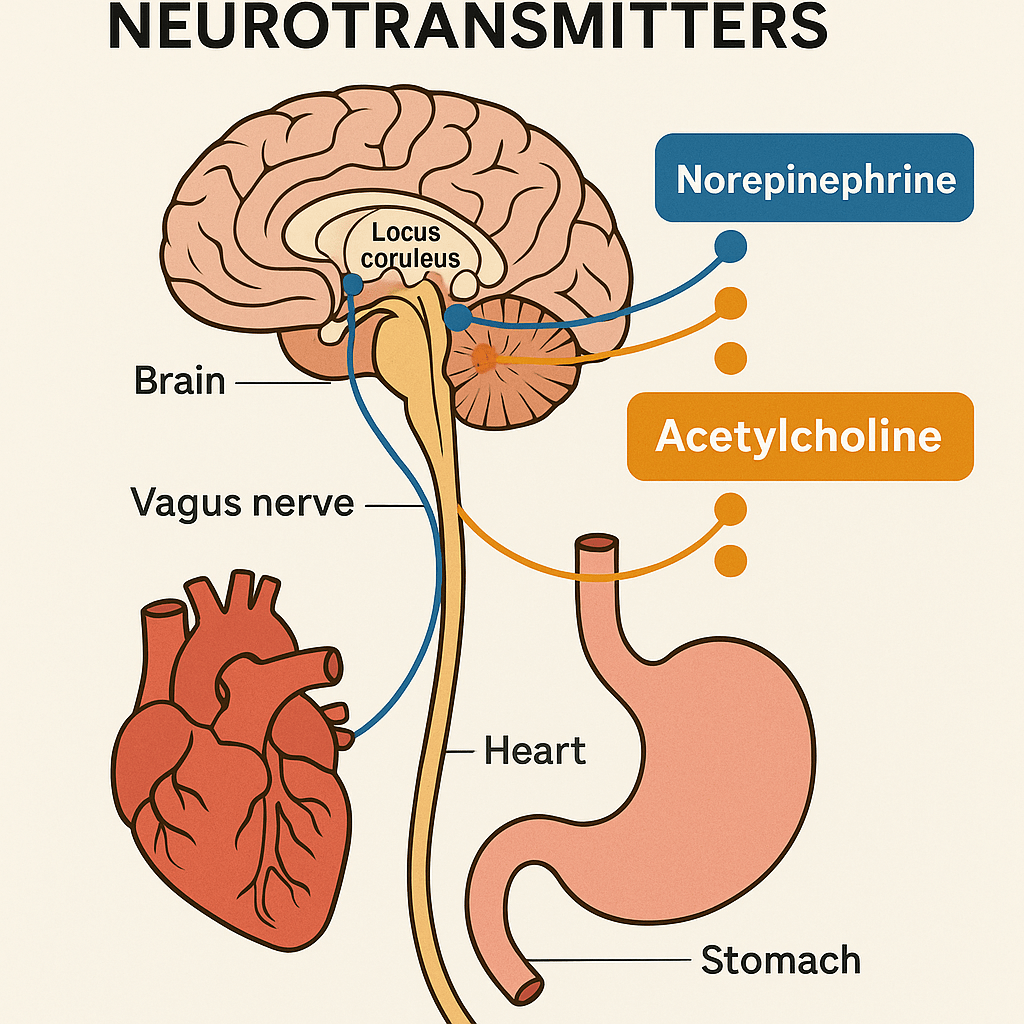

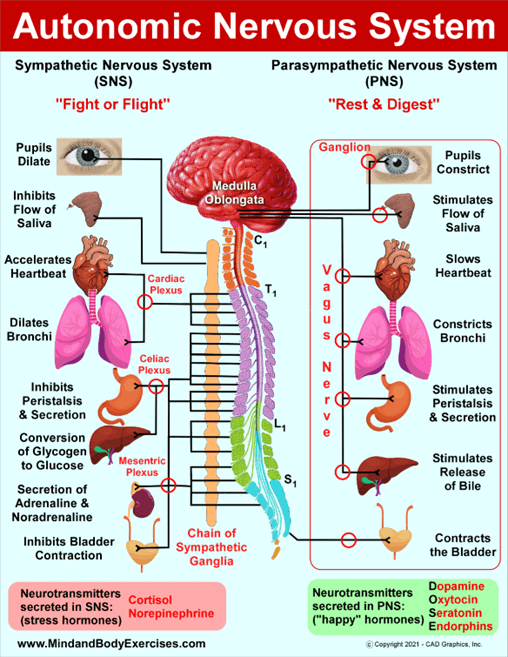

Because inner dialogue can strongly influence emotion and physiology, triggering stress responses or enhancing motivation. It plays a direct role in daily wellness.

The Relationship Between Metacognition and Inner Dialogue

Although related, these two processes serve distinct roles:

- Inner dialogue is the content of thought, with words, judgments, and narratives playing out in the mind.

- Metacognition is the process that monitors and evaluates that content, determining whether it is useful, accurate, or aligned with one’s values and goals.

For example, a negative inner dialogue may say, “I am too tired to exercise.” Metacognition, however, can step in to evaluate this thought: “Is this fatigue physical exhaustion or just lack of motivation? What choice best supports my health goals?” This oversight allows individuals to reshape self-talk into a more adaptive pattern, such as: “I will start with a light walk to see how I feel.”

In this way, metacognition acts as a regulator of the inner dialogue, creating a feedback loop in which self-awareness leads to more balanced decisions.

Implications for Holistic Health and Wellness

Mental Wellness

Unchecked inner dialogue can amplify stress, worry, or self-doubt. Metacognition provides the awareness needed to identify unhelpful thought patterns, reduce rumination, and foster cognitive reappraisal (Wells, 2002). Metacognitive therapy, for example, helps individuals gain distance from destructive inner dialogue, improving resilience and emotional balance (Normann & Morina, 2018).

Physical Health

Health behaviors such as exercise, nutrition, and sleep are influenced by the interplay between self-talk and metacognition. Inner dialogue may discourage healthy action (“I don’t have time to cook tonight”), but metacognition allows for reflection and redirection (“If I prepare something simple now, I will feel better tomorrow”). Research suggests that higher levels of metacognitive awareness correlate with proactive health behaviors (Frazier et al., 2021).

Spiritual Growth

In the spiritual dimension of wellness, metacognition and inner dialogue intersect through practices such as meditation and prayer. Inner dialogue may be quieted, observed, or transformed during these practices, while metacognition supports discernment of which thoughts are distractions, and which carry deeper meaning (Vago & Silbersweig, 2012). This reflective process nurtures clarity, purpose, and transcendence—core elements of holistic health.

Practical Applications

- Mindfulness and Meditation – Strengthen awareness of the inner dialogue and cultivate metacognitive observation without judgment.

- Reflective Journaling – Encourage conscious monitoring of thought patterns, helping distinguish helpful from harmful self-talk.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Practices – Use metacognition to challenge negative self-talk and reinforce positive, health-supporting narratives.

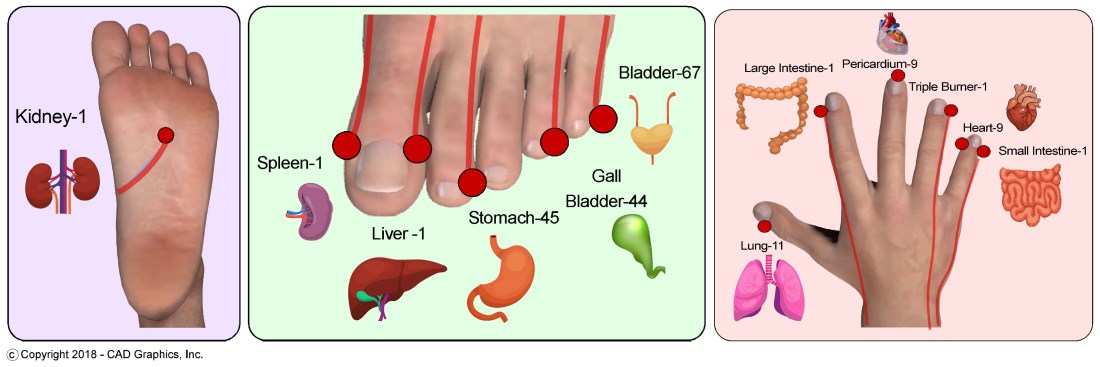

- Holistic Disciplines (e.g., Tai Chi, Qigong, Yoga) – Integrate body awareness with reflective thought, aligning physical sensations with mindful inner regulation.

Metacognition and inner dialogue are distinct yet complementary processes that shape human experience. Inner dialogue provides the immediate content of thought, while metacognition serves as the higher-order process that monitors and reshapes those thoughts. Together, they influence mental clarity, physical choices, and spiritual insight, making them central to holistic health and wellness. By cultivating both awareness of the inner dialogue and the reflective power of metacognition, individuals can foster resilience, self-regulation, and a deeper sense of integration across mind, body, and spirit.

References:

21andsensory, V. a. P. B. (2022, February 15). The constant autistic internal monologue. 21andsensory. https://21andsensory.wordpress.com/2022/02/15/the-constant-autistic-internal-monologue/

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-22098-000

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.34.10.906

Frazier, L. D., Schwartz, B. L., & Metcalfe, J. (2021). The MAPS model of self-regulation: Integrating metacognition, agency, and possible selves. Metacognition and Learning, 16(2), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-020-09255-3

Getting Started with Metacognition. (n.d.). https://theteachingthief.blogspot.com/2012/09/getting-started-with-metacognition.html

Morin, A. (2009). Self-awareness deficits following loss of inner speech: Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor’s case study. Consciousness and Cognition, 18(2), 524–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2008.09.008

Normann, N., & Morina, N. (2018). The efficacy of metacognitive therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02211

Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(4), 460–475. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1994.1033

Vago, D. R., & Silbersweig, D. A. (2012). Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): A framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 296. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00296

Wells, A. (2002). Emotional disorders and metacognition. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470713662