The concept of “born with nothing, die with nothing” is a profound philosophical idea found in many Eastern traditions, including Buddhism and Taoism. It reflects the principles of impermanence, detachment, and the cyclical nature of existence. We enter this world with no possessions, and when we leave, we take nothing with us. This underscores the transient nature of material wealth and highlights the deeper value of experiences, relationships, and inner growth.

Happiness is not about collecting material things or beautiful memories. It is about having a deep feeling of contentment and knowing that life is a blessing. – Jeigh Ilano

This idea extends beyond human life to all living beings, aligning with the concept of “no beginning, no end.” Like the yin-yang (☯) and infinity (∞) symbols, it represents the continuous flow of transformation, where emptiness gives rise to form, and form dissolves back into emptiness.

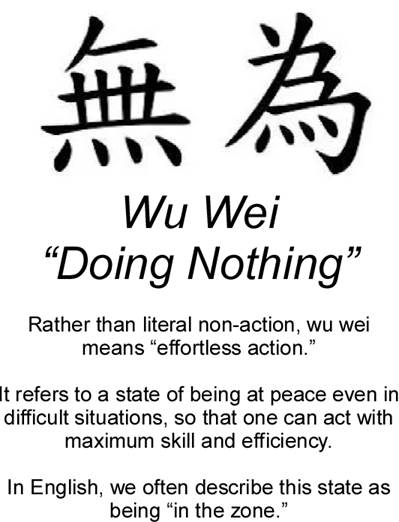

Human life can be seen as consciousness temporarily residing in form, experiencing the ever-shifting balance of existence before returning to the formless. In Taoism, this mirrors the Dao (道), the ever-flowing source from which all things arise and to which they ultimately return. Just as yin transforms into yang and vice versa, life and death are not endpoints but expressions of an eternal process. This perspective encourages non-attachment, balance, and harmony with the natural flow of life, recognizing that all physical possessions are ultimately borrowed, and everything returns to the Dao.

Related Concepts:

Biblical Perspective: A similar idea appears in the Book of Job, where Job states, “The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; may the name of the Lord be praised.” This is often interpreted as an acceptance of life’s impermanence, acknowledging that all we have is ultimately a gift and can be withdrawn at any time.

The Heart Sutra: A central text in Mahayana Buddhism, the Heart Sutra articulates the nature of emptiness, stating that all phenomena bear the mark of emptiness—their true nature is beyond birth and death, being and non-being.

Śūnyatā (Emptiness): In Mahayana Buddhism, śūnyatā refers to the understanding that all things are devoid of intrinsic existence. This insight is fundamental to recognizing the transient nature of life and the absence of a permanent self.

Samsara: This term describes the continuous cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, emphasizing the impermanence and suffering inherent in worldly existence.

Why This Concept Matters in Everyday Life

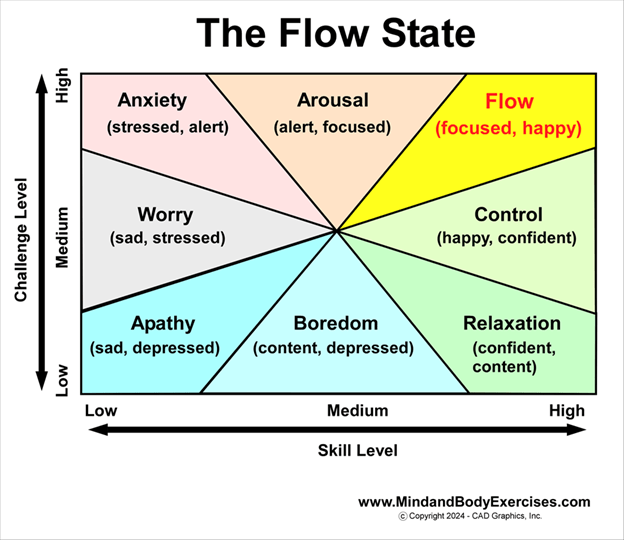

Understanding and embracing this concept can have a profound impact on how we approach daily life. It reminds us to focus on what truly matters. Our experiences, relationships, and inner development are most important, rather than being overly attached to material possessions or fleeting successes. By recognizing the impermanent nature of all things, we can cultivate greater resilience and gratitude in the face of challenges, reduce unnecessary stress, and live with greater appreciation and mindfulness.

This perspective encourages us to be present in each moment, to value the people around us, and to engage in life with a sense of peace and acceptance. It also promotes generosity and compassion, as we recognize that nothing truly belongs to us, and what we give to others is ultimately part of the greater flow of all existence.

By implementing this understanding into our lives, we can develop a deeper sense of harmony, balance, and contentment, freeing ourselves from the burdens of attachment and fear while embracing the natural rhythms of life.

I teach and offer lectures about holistic health, physical fitness, stress management, human behavior, meditation, phytotherapy (herbs), music for healing, self-massage (acupressure), Daoyin (yoga), qigong, tai chi, and baguazhang.

Please contact me if you, your business, organization, or group, might be interested in hosting me to speak on a wide spectrum of topics relative to better health, fitness, and well-being.

I look forward to further sharing more of my message by partnering with hospitals, wellness centers, VA centers, schools on all levels, businesses, and individuals who see the value in building a stronger nation through building a healthier population.

I also have hundreds of FREE education video classes, lectures, and seminars available on my YouTube channel at:

https://www.youtube.com/c/MindandBodyExercises

Many of my publications can be found on Amazon at:

http://www.Amazon.com/author/jimmoltzan

My holistic health blog is available at:

https://mindandbodyexercises.wordpress.com/

http://www.MindAndBodyExercises.com

Mind and Body Exercises on Google: https://posts.gle/aD47Qo

Jim Moltzan

407-234-0119