Stress has become known as one of the main factors contributing to the top causes of human death. Heart disease, cancer, unintentional accidents, respiratory ailments, cirrhosis of the liver and suicide are the most common causes that all share a strong connection to stress. Stress-related conditions account for more than 75 percent of all physician office visits. The autonomic nervous system (ANS), and more specifically the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is what controls the body’s physiological response to stress. Deliberate management of the SNS by regulating respiration rate and volume has been proven through medical research to lower stress.1 Qigong, tai chi, and yoga are safe, relatively inexpensive, and non-pharmaceutical options for managing stress through regulation of the SNS utilizing mindful breathing exercises.

Stress can be defined as an individual’s consciousness and body’s response to tension or pressure in regard to specific events or changes in one’s environment. Causes of stress vary widely depending upon the individual and their coping mechanisms. Much stress comes from the workplace as people struggle to manage workload, deadlines, competition, relationships, and sometimes physical changes also. These stresses can be seen or unseen by the person. Increased breathing rate is necessary when experiencing truly stressful situations, like being chased by an animal, running from a fire or similar life-threatening situations. However, continued breathing at this pace for an extended period of time puts accumulative stress on all of the body’s systems. It is also worth stating that not all stress is considered bad in that good things can arise from experiencing stress and coping with it.2

Emotional states directly influence respiration. Our emotions reveal themselves in various breathing patterns. Emotions of anger, fear, and anxiety result in quick, shallow breaths. Grief causes us to breathe spasmodically. Boredom leads to shallow breathing, while sadness and depression produces shallow and inconsistent breathing.

The average person breathes 12-18 breaths per minute (BPM) during regular activity of standing, sitting & walking, consequently engaging the sympathetic nervous system. Constant duration in the SNS dumps neurotransmitters of cortisol and norepinephrine into the blood stream putting the vital organs in a state of constant high alert and stress (see figure 1). Health and fitness experts suggest that 6 BPM is optimal for the lungs to properly oxygenate the whole body, balance the blood chemistry and also remove toxins. The lungs are responsible for removing 70% of the body’s waste by-products through exhalation. Deeper breathing is a key component to having a long and healthy life. Through focused and deliberate breathing methods, many positive mental and physical benefits can be achieved. This is more easily accomplished through mindful breathing patterns from exercises such as meditation, qigong, tai chi and yoga.3

The brain and body typically react to stress in the following steps (see figure 2):

- Receptors sense stress stimuli and send chemical signals to the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis (HPA), which releases adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) to the adrenal glands.

- The adrenal glands respond with the secretion of cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline to be released into the bloodstream.

- Immediate physiological changes are induced, including acceleration of heart and lung activity, elevated blood pressure, inhibition of digestive activity, tunnel vision, and sweating.

Long-term stress can lead to over-secretion of the adrenal steroids causing Cushing’s Disease.4

Qigong, yoga, tai chi and daoyin are quite different names for exercise methods that all share the same Eastern Indian origins (see figure 3). Tai chi is sometimes referred to as “Yoga in motion” or tai chi chuan. All of these types of exercise use mindful breathing with deliberate body positioning. The mind is focused inward on one’s thoughts, breathing and posture. All have elements for mind, body & spiritual (or higher consciousness) development. These practices have been practiced for thousands of years (origins between 5000-1500 BC), and Tai Chi originated in the 12th century. The following is a basic translation of these methods:

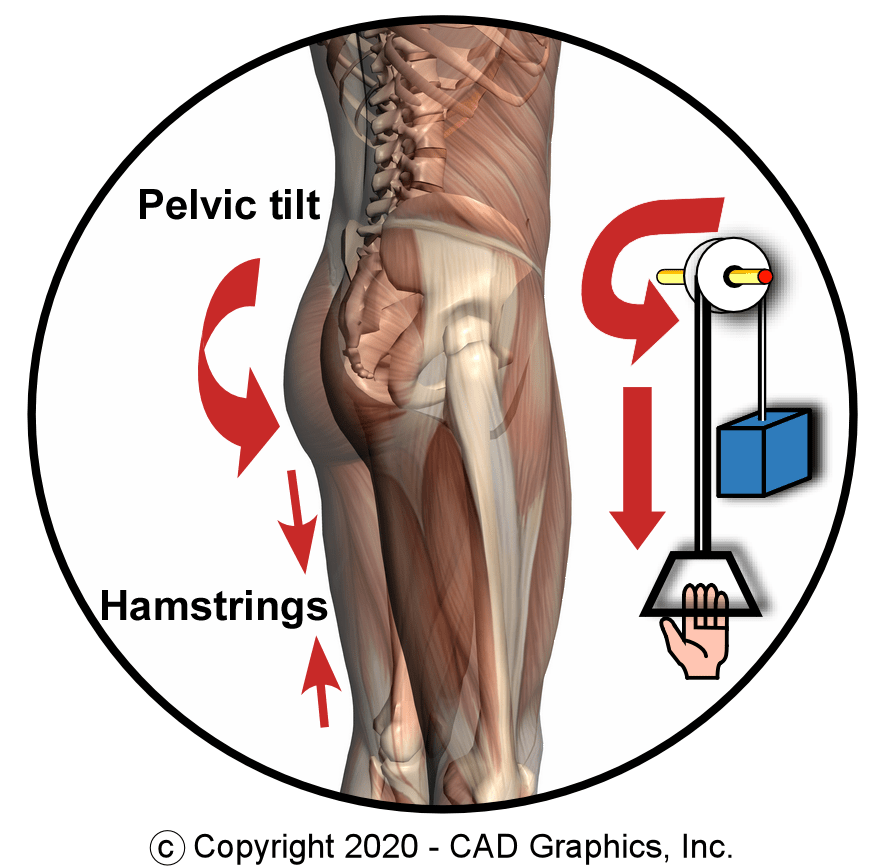

All of these methods have a strong focus on the correlation between the physiological health of the spinal column, all of its related components and the health of the central nervous system (CSN). The CSN also has a direct connection to the body’s immune system in fighting off disease and illness. The human body is made up of bones, muscles, and organs amongst other components. Veins, arteries, and capillaries carry blood and nutrients throughout to all of the systems and components. Additionally, 12 major energy meridians carry the body’s energy (see figure 4). “life force” also known as “qi”. One’s qi is stored in the lower Dan Tien. Daily emotional imbalances accumulate tension and stress gradually affecting all of the body’s systems. Stressors in the forms of discomfort, nuisances, irritations, or grudges can continue to tighten and squeeze the flow of the life force. This is where disease claims its foothold.5

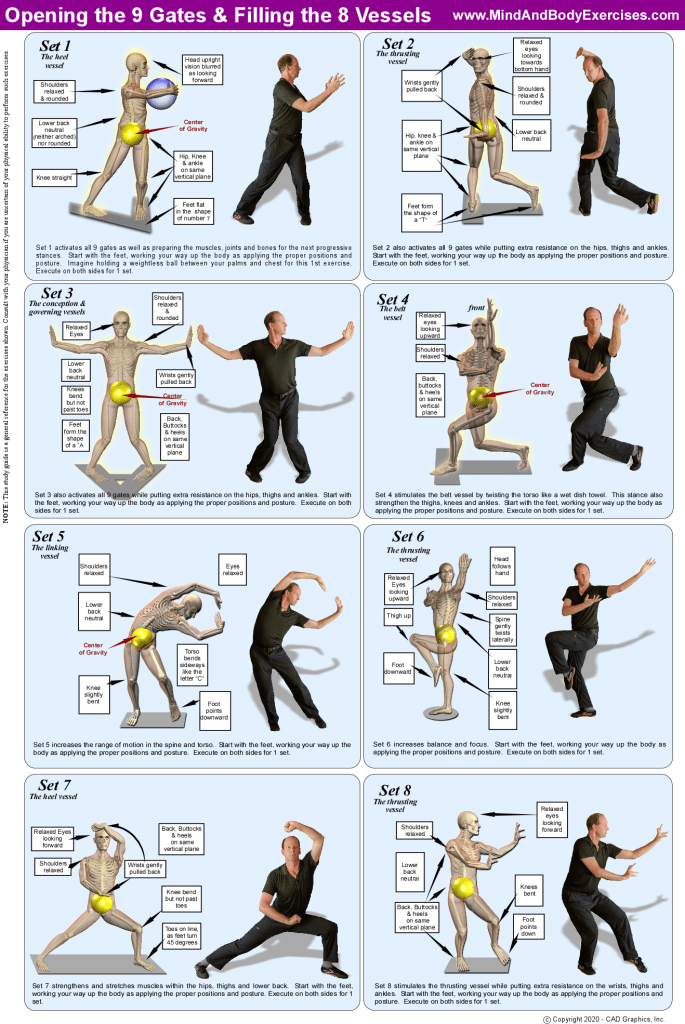

Qigong is sometimes referred to as standing-yoga, but basically qigong and yoga share the same root origin. Often people think of qigong as standing or sitting still for hours in meditation, and it can be for the advanced practitioner. People often think of yoga as sitting or lying on the ground for most of the exercises. Yoga and qigong are much the same but can differ based upon the teacher and the goals in practice. Qigong has moving exercises (tai chi and daoyin) and yoga has standing exercises (see figure 5). It all depends on who is teaching and what their background of knowledge includes.

Qigong breathing exercises can adjust the brainwaves to the theta state where the mind is relaxed and the body chemistry changes promoting natural healing. Relaxing of the deep skeletal muscles, working outward. Release of tension accumulated within the muscles, organs, and nerves. Whereas conventional physical exercise can deplete energy, Qigong helps to replenish your natural energy.6

A randomized controlled trial for qigong practices from their start date up until December 2018, included 9 studies involving depression as well as any neurophysiological and other psychological mechanisms results were included. The sample sizes varied between 24 and 116 participants, aged between 18 and 84. Within these studies, seven suggested that qigong was effective in decreasing depression, often a side-effect of stress. A noteworthy effect on lower diastolic blood pressure was also found. However, no obvious effects were reported for the levels of cortisol level nor lowering of systolic blood pressure. This trial was able to demonstrate that qigong is an effective method to reduce depression by activation of the parasympathetic nervous system.7

In a separate study, a combination of exercises from Eight Trigrams Palms (baguazhang), and will boxing (xing yi), qigong, and yoga referred to as Tai Chi synergy T1 exercise was used to determine effects on metabolism, physical fitness, and autonomic function. Participants practiced a total of 16 sessions each being for 63 minutes long. This study was conducted at the Hsinchu Armed Forces Hospital in Taiwan. 26 volunteers with history of medical illness or surgery were asked to participate. This study was able to determine that Tai Chi Synergy T1 exercises were able to significantly affect the delicate balance of autonomic control by way of increasing parasympathetic regulation while decreasing sympathetic nerve activity. Also reported were decreased were levels in serum glucose, cholesterol, body mass index and systolic blood pressure. Lastly, innate and adaptive immunity improved, as well as increased in physical fitness and physical strength for those who participated for the 10 weeks study.8

Stress is well known today to have major effects on our mental and physical health. The constant trials and tribulation that life offers can be perceived as good or bad stresses depending upon the individual. With some self-awareness, these stressors can often be minimized or channeled into positive and constructive directions. However, if left unchecked and unregulated stress can manifest into a downward spiral of disease and illness.9 It was reported that over 200 million people in China practiced qigong during the period of 1976-1990.6 In recent years the US has approximately 7.38 million adults practicing Tai chi or qigong on a regular daily basis.7. These numbers could be interpreted to support that tai chi and qigong practices have been gaining much popularity outside of Asia.

References:

1HARTZ-SEELEY, D. (2014, March 21). Chronic stress is linked to the six leading causes of death. Miami Herald. https://www.miamiherald.com/living/article1961770.html

2 Tripathy, M. (2018). Recognizing & Handling the Underlying Causes of Stress at Workplace: An Approach through Soft Skills. International Journal of Management, Accounting & Economics, 5(7), 619–632. https://search-ebscohost-com.northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=buh&AN=131442513&site=eds-live

3 Russo, M. A., Santarelli, D. M., & O’Rourke, D. (2017). The physiological effects of slow breathing in the healthy human. Breathe (Sheffield, England), 13(4), 298–309. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.009817

4 Martini. (2018). Fundamentals of Anatomy & Physiology (11th Edition). Pearson Education. https://etext-ise.pearson.com/courses/billings-berg24639/products/GG5B16RZ5RZ/pages/a2abdb984e64b10869b4a3b46925d026a2b088597?locale=&key=1331522889929302931102021&iesCode=H66h4TVVOS

5 Chen, X., Cui, J., Li, R., Norton, R., Park, J., Kong, J., & Yeung, A. (2019). Dao Yin (a.k.a. Qigong): Origin, Development, Potential Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Evidence – Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A612030915/HWRC?u=vol_l99n&sid=HWRC&xid=996081b2

6 Yeung, A., Chan, J. S. M., Cheung, J. C., & Zou, L. (2018). Qigong and Tai-Chi for Mood Regulation. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing), 16(1), 40–47. https://doi-org.northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20170042

7 So, W. W. Y., Cai, S., Yau, S. Y., & Tsang, H. W. H. (2019). The Neurophysiological and Psychological Mechanisms of Qigong as a Treatment for Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 1–13.https://search-ebscohost-com.northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edb&AN=139868729&site=eds-live.

8Tai, H.-C., Chou, Y.-S., Tzeng, I.-S., Wei, C.-Y., Su, C.-H., Liu, W.-C., & Kung, W.-M. (2018). Effect of Tai Chi Synergy T1 Exercise on Autonomic Function, Metabolism, and Physical Fitness of Healthy Individuals. Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine (ECAM), 2018, 1–7. https://doi-org.northernvermont.idm.oclc.org/10.1155/2018/6351938

9 Chun-Yi, L. (2018, April 2). Acute Physiological and Psychological Effects of Qigong Exercise in Older Practitioners. US National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902057/#:~:text=In%20conclusion%2C%20one%20session%20of,qigong%20exercise%20in%20older%20practitioners

Additional References (graphics)

Moltzan, J. (2021a). Figure 1. Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Nervous System [Graphic]. In Self-published.

Moltzan, J. (2020b). Figure 2. Stress Response [Graphic]. In Self-published.

Moltzan, J. (2021c). Figure 3. Methods That Activate the Parasympathetic Nervous System [Graphic]. In Self-published.

Moltzan, J. (2021d). Figure 4. The 12 Primary Energy Meridians [Graphic]. In Self-published.

Moltzan, J. (2021e). Figure 5. Various Stress Relief Methods [Graphic]. In Self-published.