The Boiling Frog of Belonging: How High-Control Groups Capture Us (A Journey Through Martial Arts, Immersion, and Awakening)

Many people enter martial arts schools, spiritual communities, or exclusive organizations seeking fitness, discipline, purpose, or belonging. Yet what begins with training can, in some cases, evolve into an insular, high-control closed environment that slowly demands total conformity. This article integrates firsthand experiences with sociocultural analysis, exploring how these dynamics unfold, how they draw in even intelligent and educated individuals, and how they can be recognized and overcome.

Humans often have short memories for uncomfortable truths we’d rather not acknowledge. When we fail to remember or record history, we invite it to repeat. Revisiting these experiences today helps us confront patterns that could otherwise recur unchallenged. While most people grow older, they do not necessarily grow wiser. Physical age and mental growth or wisdom do not always increase together. I want to believe that people and their behaviors can change and evolve for the better. A caterpillar eventually transforms into a butterfly. Yet we must also recognize that, as the saying goes, “a tiger cannot change its stripes.”

I am not sharing this to assign blame, demand accountability, or even to provide perfect clarity. Everyone who was involved knows, to some degree, what transpired. I do not see myself as a victim; I, too, was a willing participant for two decades, rationalizing along the way that the “ends would justify the means,” until I chose to stop being compliant. Today, it matters less to me whether others have changed or evolved, as that is their path, their journey, and their challenge to resolve within themselves. What matters most is what I have learned and earned. Inner transformation and self-mastery, ironically, can emerge in spite of, or perhaps because of, the very circumstances we experience firsthand.

What makes me qualified to speak on this topic?

I was deeply involved in a high-control closed martial arts group for 20 years, serving in positions of authority as a senior-level instructor, mid-to-upper management, and as an owner of multiple locations. Years later, after decades of research, conducting numerous interviews with individuals from diverse backgrounds both within and beyond the martial arts world, and pursuing higher education, I believe I am a credible resource to speak on this topic.

Part I: How High-Control Martial Arts & Other Groups Draw You In

The Bait: Personal Desires and the Illusion of Fulfillment

High-control groups thrive by mirroring what potential members most deeply want: mastery, inner peace, community, etc. They craft an environment that reflects those desires, creating a powerful sense of destiny and belonging. As described in one firsthand account:

“I was a discontent 19-year-old, searching for meaning in a world that felt broken. The school I found promised not just martial arts but enlightenment, peace, and brotherhood. They offered exactly what I was longing for, and I was hooked.”

Different Experiences, Different Interpretations

It’s essential to recognize that not everyone in a high-control environment shares the same experience, even when standing in the same room. Individual memories and interpretations are shaped by personal histories, perceptions, and expectations, like siblings recalling the same childhood differently as adults. Many members gained meaningful benefits from training in this system, including friendships, exposure to Asian culture, and valuable traits such as cultivating a “can-do attitude.” Others, however, experienced harm and disillusionment. Ironically, one of my own most significant lessons was learning how not to treat or interact with other people, especially recognizing the importance of never taking advantage of others for personal gain. Both positive and negative perspectives are real, valid, and necessary to understand the full picture.

The Con: How Desire Enables Entrapment

The foundation of any effective con is mutual participation: it cannot succeed unless the “mark” wants what’s being offered. In high-control martial arts environments, the leadership uses students’ own goals to pull them deeper. It’s not that people don’t see the red flags; it’s that they rationalize them away because the group appears to offer what they crave most. This is why even highly educated professionals, trained to think critically, can fall prey. They are often convinced they’re fulfilling a noble or enlightened purpose.

High Achievers Are Not Immune

Doctors, lawyers, college professors, firefighters, law enforcement, and other accomplished and educated professionals are just as susceptible to immersion in high-control environments as anyone else. This group strived to bring these types of people into the fold, not only for their income but also their access to power, influence, and other resources. It is a mistake to assume that education or social status alone shields a person from manipulation. In fact, those with strong ambitions, high standards, or deep desires for excellence can be especially vulnerable when a group appears to promise fulfillment of those ideals.

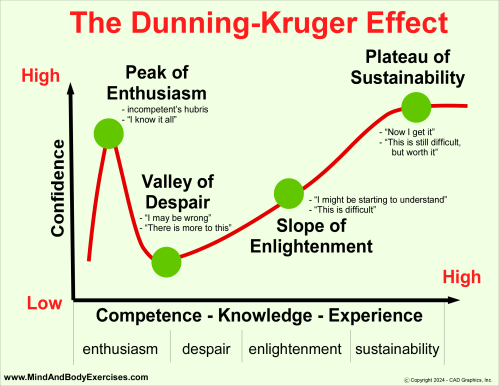

Overconfidence and the Dunning-Kruger Effect

Another factor that can blind even intelligent, capable individuals to a high-control group’s manipulation is the Dunning-Kruger Effect, a cognitive bias in which people with limited knowledge or experience overestimate their competence (Dunning & Kruger, 1999). This misplaced confidence can lead new members, or even seasoned instructors who’ve gained some amount of knowledge, to believe they fully understand martial arts, philosophy, or personal development more deeply than they actually do, leaving them vulnerable to manipulation.

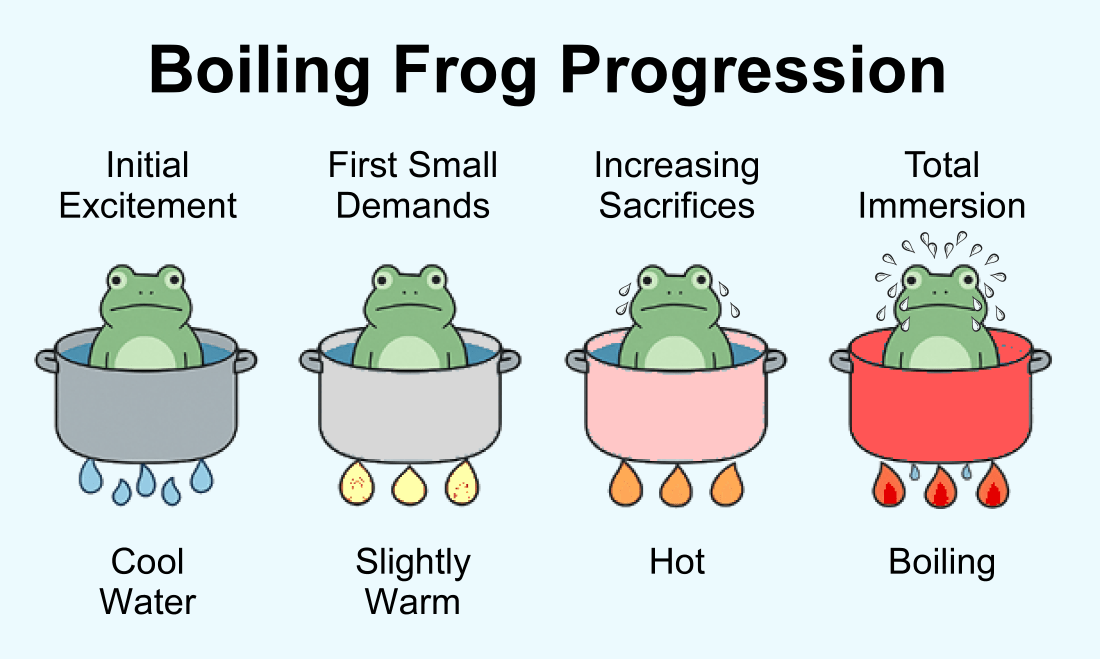

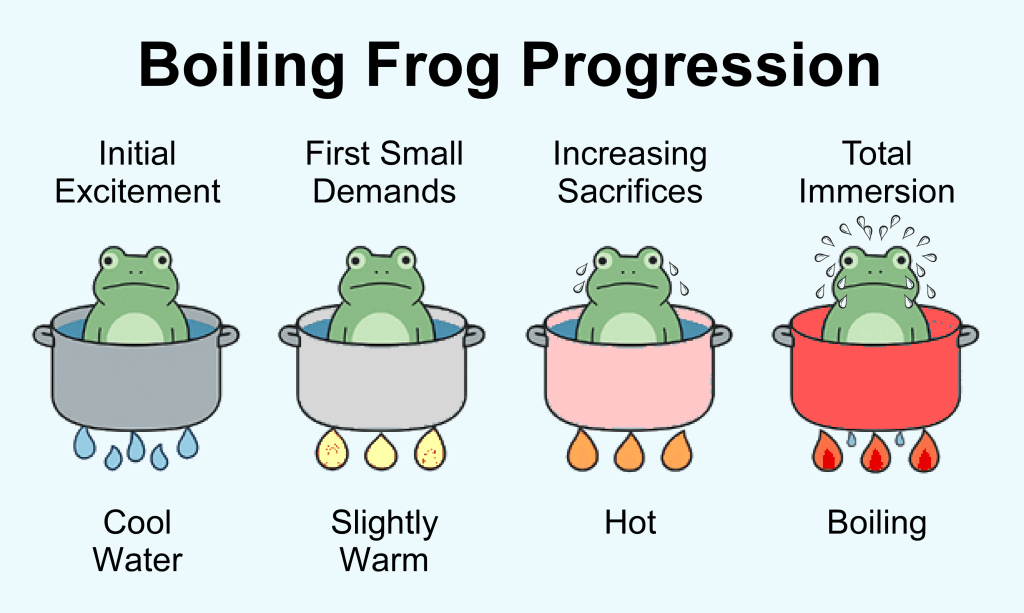

The Immersion by Degrees: Small Steps Toward Total Commitment

High-control groups rarely show their true face at first. They escalate demands gradually. Small favors become hours of service; a few classes become total life dedication. This mirrors the boiling frog metaphor: a frog placed in cool water that is slowly heated will fail to notice the danger until it is too late (Hoffer, 1951). In high-control groups, each incremental step normalizes the next, shifting members’ sense of what is acceptable and desirable. One signs up to become stronger, better, more confident. But in time, they find themselves painting houses, fixing cars, cutting lawns, and picking apples from trees. Others, even those considered high-level 7th- and 8th-degree martial arts practitioners, found themselves at the grandmaster’s beck and call, running errands, picking up his children from school, or maintaining homes late into the night for other members of the grandmaster’s family. And even others would come to find out that their wives were being violated by the grandmaster (as alleged by multiple high-level former members) while they were away handling other school business. But they all originally signed up because they just wanted to be better.

The Demand: Conformity and Life Domination

A high-control environment crosses a critical line when it demands:

- Adoption of the group’s beliefs as absolute truth.

- Isolation from family, friends, and outside perspectives.

- Complete control over finances, living arrangements, and time.

As one former member described:

“My days extended to 16, even 22 hours of training, chores, and teaching. I stopped seeing friends. My world shrank to the group and its leadership. Doubt became synonymous with betrayal”

Part II: The Mechanics of Control – Testing, Indoctrination, and Financial Exploitation

The Tests: Can You Be Controlled?

Early tests appear benign: running errands, buying lunch/dinner, staying late, or accepting unusual requests. Compliance opens the door to greater demands such as:

- “Do you know someone?”

- “Can you access some information?”

- “How hard would it be to….?

Each act reinforces members’ willingness to surrender autonomy.

Indoctrination Through Exhaustion

After grueling physical sessions, mental and emotional defenses are lowered. Doctrinal messages “Only we know the truth,” “Others won’t understand,” are then delivered. This alternating pattern of exhaustion and indoctrination is a hallmark of high-control environments (Lifton, 1961). Intense physical exhaustion impairs critical thinking by depleting cognitive resources (Hockey, 2013), while acetylcholine enhances selective attention to salient stimuli, such as a leader’s directives (Sarter et al., 2006). Under fatigue, chaotic neural dynamics further disrupt prefrontal cortex function (Freeman, 1994), reducing skepticism and increasing reliance on group authority. This neurobiological triad (exhaustion + hyperfocus + disrupted judgment) creates fertile ground for compliance.

Financial Exploitation

High-control martial arts and self-help groups often sell an endless series of advanced courses, each promising unique secrets and requiring ever-larger payments. Promotions and rank tests become both a symbol of loyalty and a financial trap. Students believe they are climbing a ladder to mastery when in reality they are climbing deeper into dependence.

Part III: Recognizing the Trap – Signs of an Insular, High-Control Dynamic

Shifts from Enthusiasm to Dependency

- When training becomes the center of identity, eclipsing other relationships and interests.

- When intuitive feelings of unease are rationalized away: “I’ve come too far to turn back now.”

Isolation from Outside Perspectives

- Members are discouraged or forbidden from studying with other teachers or seeking alternative viewpoints.

- Outsiders are framed as confused, ignorant, misguided, or even enemies.

- This dynamic reflects classic groupthink theory, where pressure for conformity and insulation from dissenting voices fosters poor decision-making and blind loyalty (Janis, 1972).

Hierarchy and Absolute Authority

- A central leader portrayed as infallible.

- This reflects what sociologist Max Weber described as “charismatic authority,” where devotion to an individual perceived as extraordinary cements hierarchical control (Weber, 1947).

- Senior members policing behavior and loyalty.

Total Lifestyle Control

- Living with fellow members to ensure surveillance and group reinforcement.

- Careers guided or manipulated to keep members financially tied to the group.

When the Most Loyal Turned Away

Fourteen upper-management instructors, including the master at the top of this organization, were incarcerated for federal crimes. Most served approximately 4.5 years in federal prison. Upon their release, only four members returned to the master’s tutelage. The other eight former managers broke with the organization entirely, with some going on to mentor others about the abuses they once participated in or witnessed. Some of those have seemingly fallen off the face of the earth and want no contact with anyone ever connected to this group.

This is significant because these individuals were among the most loyal to the founder and considered the most qualified high-level practitioners. Many who once enforced the system’s harshest controls were later speaking out against it or at least demonstrating their rejection by refusing to return to the “old school ways.”

I personally knew and learned from most of the top instructors who were later incarcerated. For some, I trained with them only occasionally, but with others, I studied under them extensively for many years. I benefited greatly from these individuals, as I genuinely liked them and deeply respected their martial arts abilities and knowledge. However, as I grew wiser and recognized that many of them lacked a moral compass or treated serious ethical matters flippantly, it became increasingly difficult to accept their guidance on life, direction, or any discussions of morality and ethics.

Over time, I came to respect those who left the group at this level, realizing they had developed a better ability to distinguish between what was true, right, and correct.

Addressing “That Was Then, This Is Now”

Some current leaders of this organization may claim, “That was then; this is now,” suggesting that the abuses of the past are no longer relevant because the individuals responsible are gone. Yet a closer look reveals a different reality: today’s upper management includes original managers who were themselves incarcerated for their roles in the organization’s wrongdoing, or others who, while not imprisoned, were fully aware of or complicit in the questionable practices that occurred.

There was an overwhelming degree of coercion, deception, and manipulation originating from the top members of this organization. Whether the grandmaster directly orchestrated this behavior, actively encouraged it, was complicit by turning a blind eye, or though least likely, was entirely oblivious to these actions, the result is deeply troubling. Regardless of the explanation, such widespread misconduct stands in stark contrast to the image of someone claiming to embody high moral character or serve as a spiritual leader.

This continuity of leadership raises important questions about whether the group has truly changed, or whether the same patterns of control, secrecy, and abuse remain embedded in its structure. If behaviors have truly changed, how sad that self-reflection only came about due to so many sincere, good-hearted and well-meaning people having left this organization.

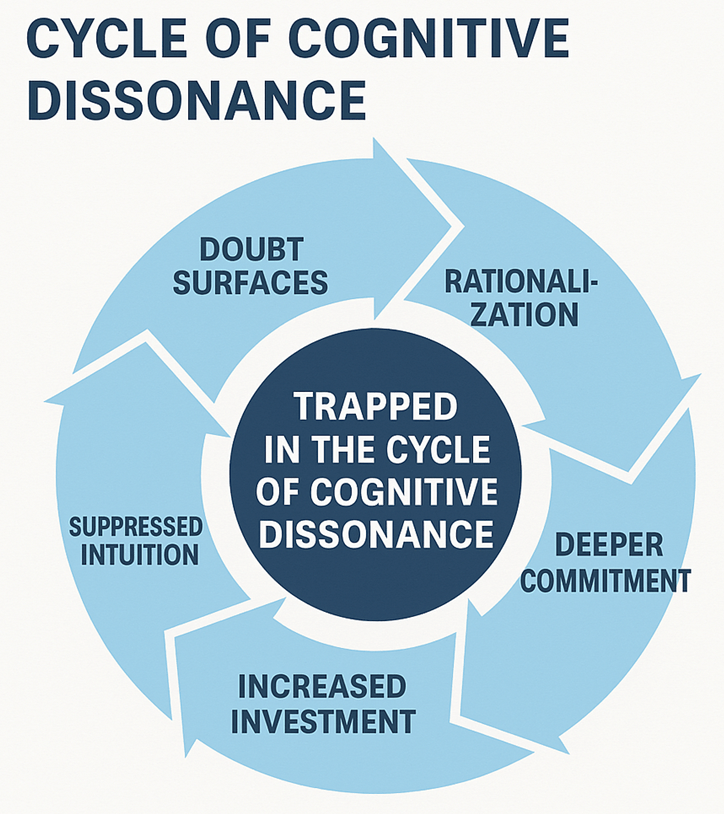

Part IV: The Battle Between Intuition and Rationalization

A key insight from my experiences is the conflict between gut instinct and self-justification. Early in immersion, most members sense subtle discomfort. Something feels “off.” But instead of heeding this intuition, they explain it away:

- “This level of discipline is just what I need.”

- “Everyone else seems fine; I must be the one with doubts.”

This process of cognitive dissonance causes people to ignore warning signs and deepen their commitment (Festinger et al., 1956). The greater the investment, the harder it becomes to acknowledge the truth.

Part V: The Boiling Frog – Immersion by Degrees

The vivid use of the boiling frog metaphor deserves emphasis:

“Each step was only slightly more extreme than the last. By the time we faced bizarre or abusive practices, they felt normal compared to yesterday”

This gradualism makes high-control groups especially dangerous: they do not demand total loyalty overnight, but cultivate it through subtle, cumulative steps. This pattern of gradual escalation aligns with the “foot-in-the-door” technique described in social psychology, where compliance with small requests increases the likelihood of agreeing to larger ones over time (Freedman & Fraser, 1966).

It’s important to recognize the significant difference between incremental indoctrination or grooming, where gradual exposure is used to normalize harmful or abusive dynamics and incremental training of the mind, body, and spirit, which is a deliberate progression designed to foster genuine improvement and self-mastery. True martial arts and self-mastery types of instruction should guide students through gradual challenges to build skills, confidence, and character, not to manipulate or erode their autonomy.

Part VI: Parallels Across Culture – Sports, Religion, and Beyond

“One person’s culture is another person’s cult.”

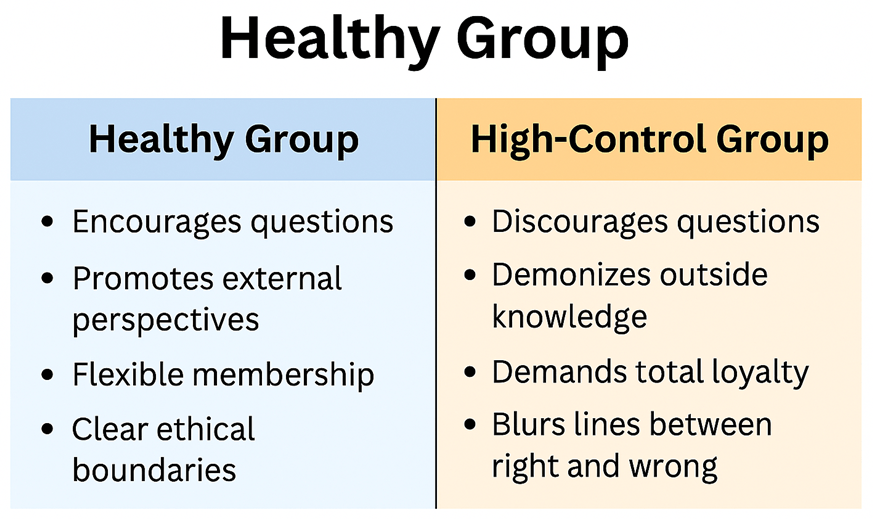

This saying captures how rituals, loyalty, and hierarchical structures can feel like supportive traditions to some, yet oppressive or manipulative to others. Recognizing these parallels helps us understand that intense commitment or exclusive practices are not inherently abusive, but can become dangerous when questioning is discouraged, outsiders are demonized, and absolute loyalty is demanded.

Reflections on sports and religion show similarly how rituals, specialized jargon, uniforms, and passionate loyalty exist in many groups that are not inherently harmful. Sports fans, military units, and religious communities often foster unity through shared traditions. Yet, as we can observe, these elements can be twisted when groups:

- Discourage outside perspectives.

- Frame dissenters as unworthy.

- Require absolute loyalty.

This parallels research showing that when group dynamics become rigid, they can turn into echo chambers where questioning is stifled (Kottak, 2019; Peretz & Fox, 2021).

Part VII: Breaking Free – The Psychological Struggle

Seeing the Truth

Admitting a group’s true nature can be harder than enduring it. Even overwhelming external evidence (e.g., investigative exposés) may initially be rejected. As one former member recounted:

“I saw a week-long investigative series revealing our group’s abuses. My first reaction was outrage — at the reporters. It took time for reality to break through the indoctrination”

Reassessing the Dream

Leaving often requires reassessing the fantasy that drew one in. This is difficult, as these dreams shape identity. Letting go feels like losing oneself, but it is a necessary step toward recovery.

Rebuilding Identity

Breaking free means redefining oneself outside the group’s narratives:

- Recognizing what skills and lessons can be retained without toxic elements.

- Building new relationships.

- Pursuing goals based on personal values, not imposed ideology.

VIII: Lessons Learned – Value and Resilience

Experiences in high-control groups can leave scars but also forge strength. Discipline, perseverance, and mental resilience gained through hardship can serve individuals well after they leave. As one survivor noted:

“What most see as problems today are nothing compared to what I survived. It taught me I could face anything”

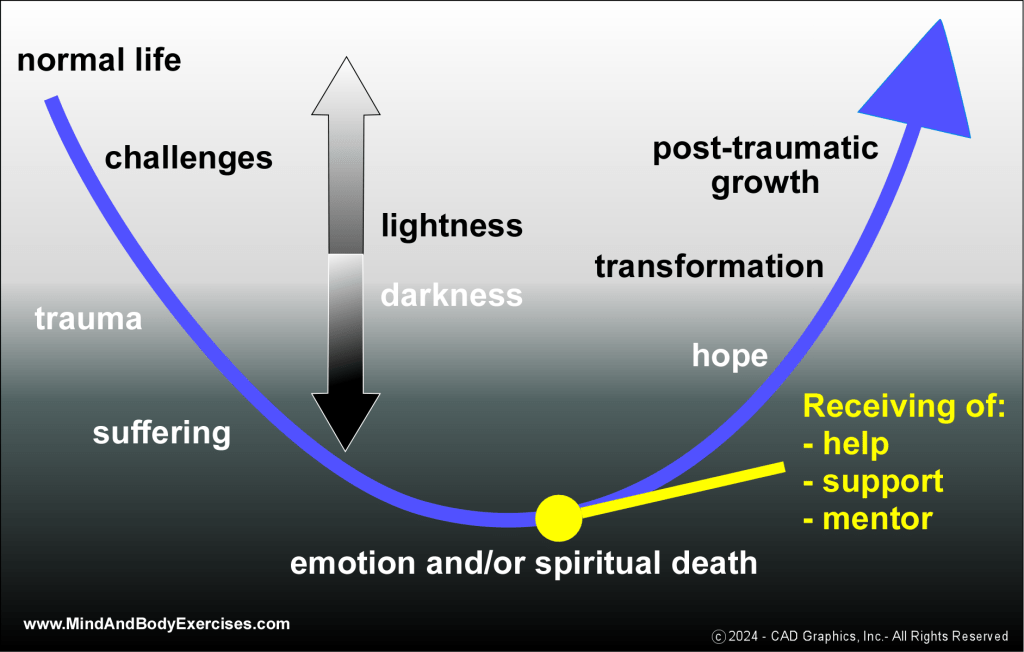

Post-Traumatic Growth: Transforming Adversity into Strength

While surviving a high-control environment can leave lasting scars, it can also create an opportunity for post-traumatic growth (PTG). PTG refers to positive psychological change experienced as a result of struggling with challenging circumstances (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). For some, leaving an abusive or manipulative group can spur a newfound personal strength, deeper relationships, openness to new possibilities, and a greater appreciation for life. Recognizing these possibilities can empower survivors to move beyond their past, knowing their experiences do not define who they are, but can shape them into wiser, more resilient individuals.

Part IX: Beyond Martial Arts – Creating Ethical Communities

Not every passionate or exclusive group is dangerous. Closed groups can preserve traditions and foster focused learning, but also exist within ethical communities:

✅ Encourage critical thinking and questions.

✅ Allow members to seek outside perspectives.

✅ Balance loyalty with autonomy.

✅ Maintain transparency about teachings and leadership.

Conclusion

Those that need to hear of this information will have read this far. Those unwilling to consider these facts may remain in denial, but this work is here for those ready to see. High-control dynamics can emerge in any setting, from martial arts schools to religious organizations or corporate cultures. Recognizing signs of manipulation, immersion by degrees, discouraging outside viewpoints, financial exploitation, etc. Authentic communities foster growth through openness, humility, and respect, not fear or blind loyalty. They seek to empower individuals to protect themselves and others.

If this article resonates with you, considering reading my book that elaborates on these topics but with more depth for personal growth and self-transformation. Find it at: https://a.co/d/hxPahVX

References

Dunning, D., & Kruger, J. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When Prophecy Fails. Harper-Torchbooks.

Freeman W. J. (1994). Role of chaotic dynamics in neural plasticity. Progress in brain research, 102, 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60549-X

Freedman, J. L., & Fraser, S. C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(2), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023552

Hockey, R. (2013). The psychology of fatigue. Cambridge University Press.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781139015394

Hoffer, E. (1951). The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements. Harper.

Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink: A psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes. Houghton Mifflin.

Kottak, C. P. (2019). Mirror for Humanity: A Concise Introduction to Cultural Anthropology. McGraw-Hill.

Peretz, E., & Fox, J. A. (2021). Religious discrimination against groups perceived as cults in Europe and the West. Politics, Religion & Ideology, 22(3-4), 415–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2021.1969921

Sarter, M., Gehring, W. J., & Kozak, R. (2006). More attention must be paid: the neurobiology of attentional effort. Brain research reviews, 51(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.002

Statista. (2023, May 4). Sports fans share in the U.S. 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/300148/interest-nfl-football-age-canada/

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

YPulse. (2023, June 15). NA vs WE: Who Are the Bigger Sports Fans? https://www.ypulse.com/article/2022/05/19/we-na-vs-we-who-are-the-bigger-sports-fans/