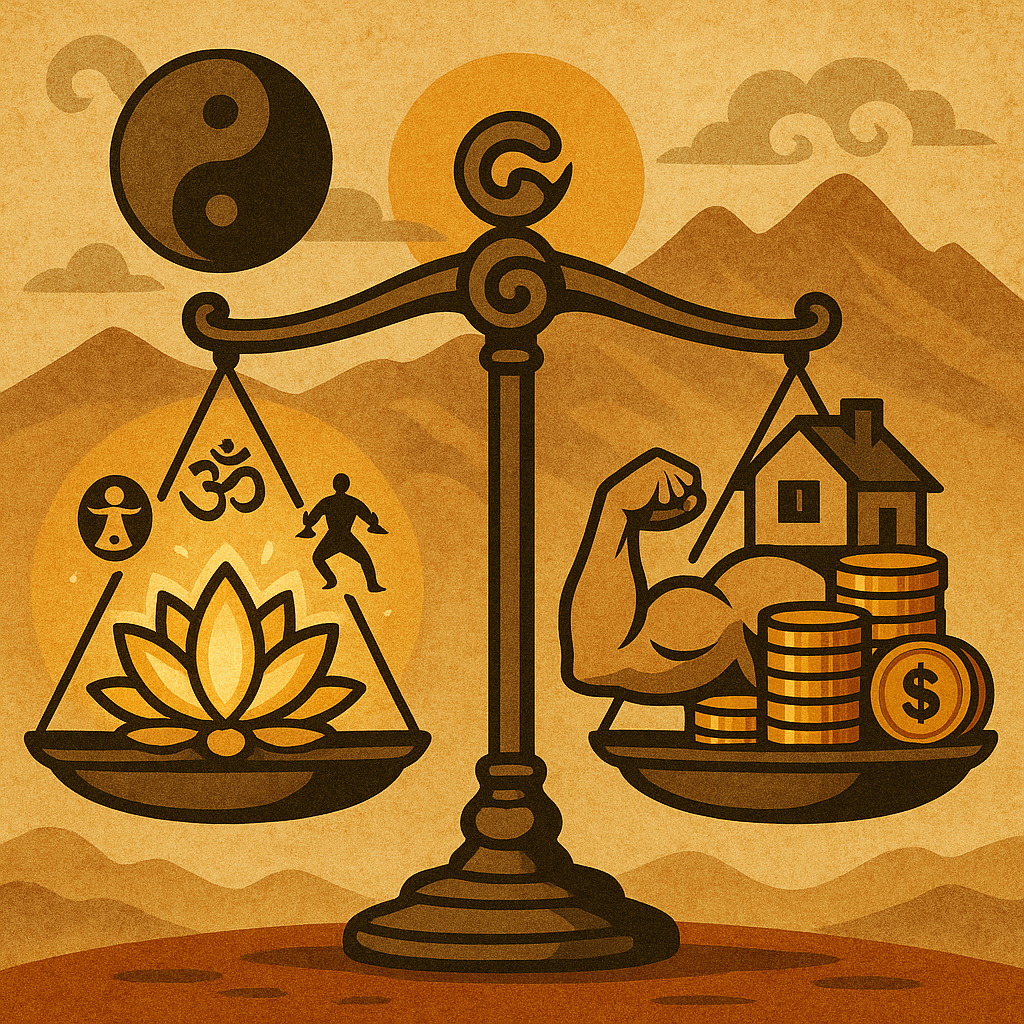

In the pursuit of personal evolution, many traditions emphasize the renunciation of material wealth as a path to spiritual enlightenment. Yet this view may overlook an essential truth: the mastery of life requires full engagement with both the spiritual and material realms. Rather than rejecting worldly success, a more holistic path invites individuals to develop discipline, embrace responsibility, and integrate spiritual realization with material abundance.

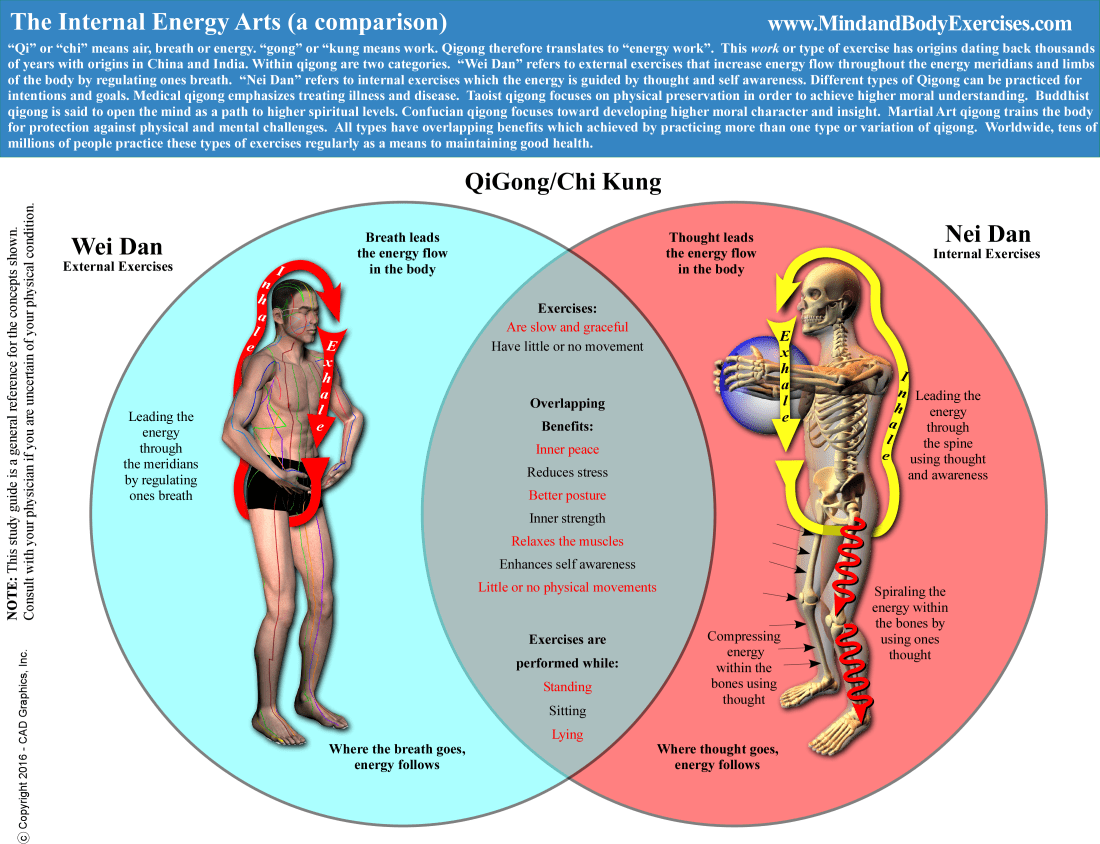

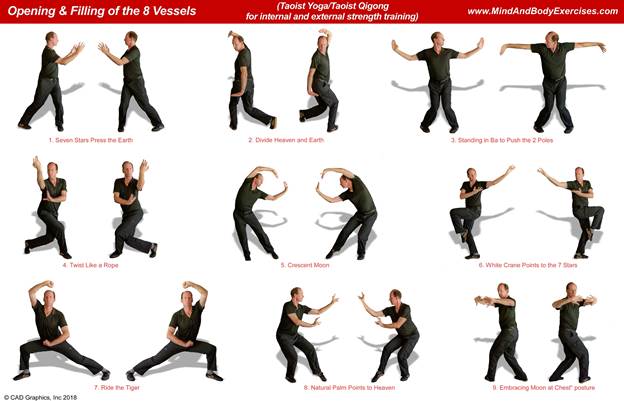

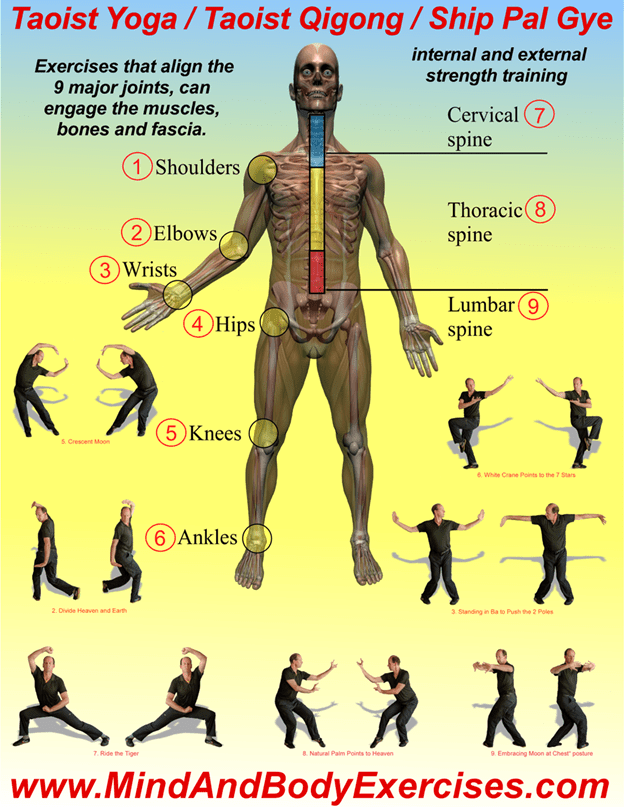

A balanced life requires strength across physical, emotional, and spiritual dimensions. True power, especially in men, is not measured by dominance or accumulation alone, but by maturity and restraint. Without discipline, power can become dangerous, giving rise to instability and harm. Therefore, self-mastery begins with a commitment to personal responsibility, training the body, focusing the mind, and cultivating inner peace.

One foundational concept in this approach is the idea that wealth and health are not opposites of spiritual life but necessary stages in the ladder of awakening. Through conscious acquisition and enjoyment of material pleasures—followed by the ability to release attachment—one gains not only experience but freedom from the cycles of craving and aversion. This path requires mastering the “world of form,” learning to participate in it fully without being controlled by it. Those who avoid or bypass this stage may find themselves spiritually incomplete. If one believes in reincarnation, this situation may lead to further experiences in future lifetimes to fully integrate these unlearned lessons.

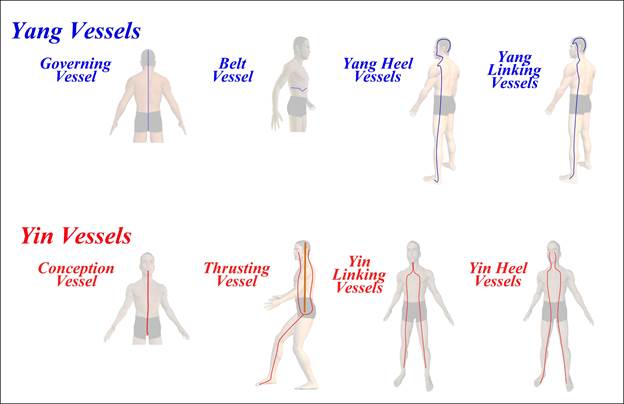

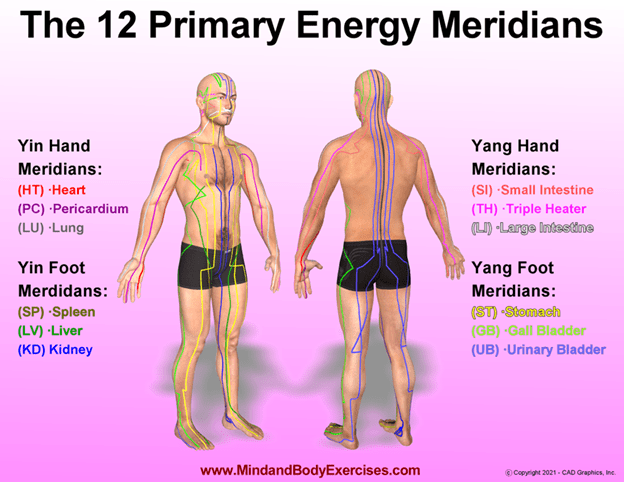

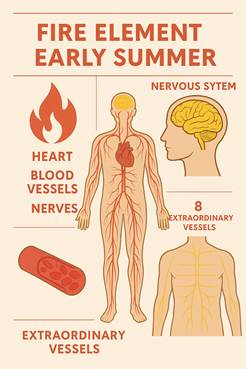

Conscious development can be mapped through the lens of energy centers or chakras, where each stage corresponds to an essential life lesson: from physical grounding and pleasure to peace, joy, love, compassion, and ultimately ecstatic or blissful states of awareness. These are not mere metaphors but practical tools for tracking one’s evolution. A person who cannot access joy or inner peace may need to revisit the foundations of health, safety, and stability before advancing into higher spiritual states.

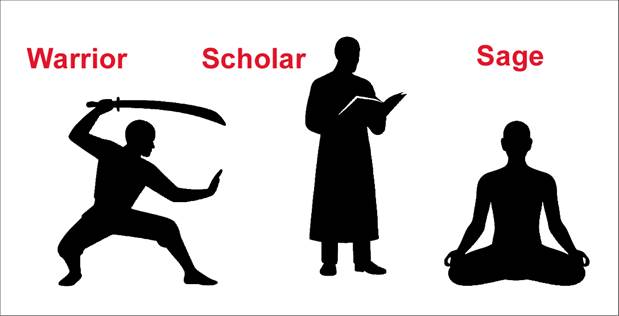

Central to this journey is the rejection of victimhood. Blaming society, circumstances, or others for one’s failures hinders growth. Only by accepting full responsibility for one’s health, finances, relationships, and spiritual development can one initiate true transformation. This principle applies across life stages, which can be seen as cycles: childhood (0–8), adolescence and young adulthood (8–33), fruition (33–58), correction (58–83), and ultimately the sage or spirit phase (83–108). Each phase carries its own lessons and demands appropriate effort and reflection.

In later life, aging should not be viewed as decay, but as a biological and spiritual opportunity. With proper practice through breathwork, meditation, physical cultivation, and mental clarity, many signs of aging can be reversed or mitigated. The aim is to remain vibrant, focused, and spiritually prepared for death, which, when acknowledged consciously, becomes a motivator for authentic living.

The role of family, lineage, and tradition is also pivotal. Respect for one’s parents and ancestors does not require blind obedience or emotional entanglement but calls for honoring their place in one’s development. This maturity fosters generational healing and sets an example for those who follow.

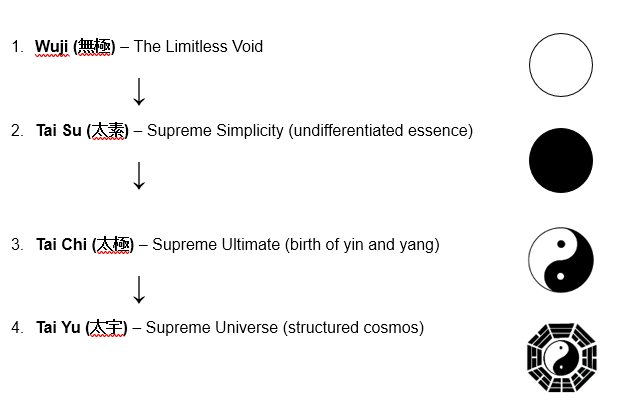

Integration of spiritual wisdom with material responsibility is not unique to any one culture. Whether through Christian parables, Taoist discipline, or Buddhist insight, timeless truths emerge: the value of discipline, the importance of presence, the need for compassion, and the certainty of death. When viewed through this inclusive lens, spirituality becomes less about belief and more about the embodiment of universal principles.

The ideal individual, a strong, wise, and compassionate being, embodies the archetype of the strategist and warrior. Not through brute strength or spiritual aloofness, but through the unification of effort, enjoyment, reflection, and humility. Mastery is not found in a cave or an office alone, but in the weaving of both. When one lives fully, without excuses or illusions, the path reveals itself not above the world, but through it.