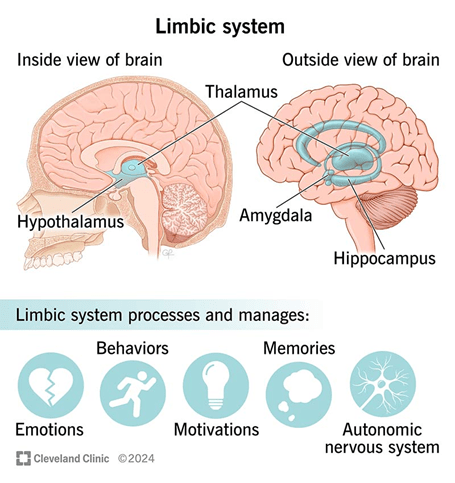

Pain is not solely a sensory experience. It is also deeply emotional, influenced by context, memory, expectation, and mood. While the somatosensory cortex processes the discriminative (sensory) aspects of pain, such as location, intensity, and duration, the limbic system, particularly the amygdala and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), mediates its affective (emotional) and motivational components (Apkarian et al., 2005; Leknes & Tracey, 2008).

1. The Amygdala: Fear, Salience, and Emotional Memory

The amygdala is a central structure in emotional processing, especially in the encoding and recall of fear and threat-related memories. It plays a critical role in the emotional coloring of pain and how we anticipate and respond to it.

- The amygdala receives nociceptive input via the spino-parabrachial pathway and from higher-order cortical areas, allowing it to influence both immediate emotional reactions to pain and pain-related memory (Neugebauer et al., 2004).

- It activates autonomic and behavioral responses to pain (e.g., anxiety, avoidance), especially when pain is perceived as threatening or unpredictable.

- Amygdala hyperactivity has been linked with chronic pain conditions, where emotional reactivity and threat perception become amplified (Simons et al., 2014).

In other words, the amygdala adds emotional salience to nociceptive stimuli, transforming a mere sensory signal into a subjectively distressing experience.

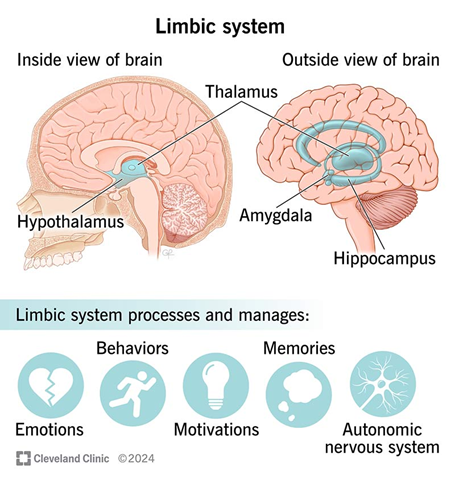

2. The Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC): The Distress and Motivation Circuit

The ACC, particularly its rostral and dorsal regions, plays a central role in pain unpleasantness, emotional suffering, and motivational drive to escape or alleviate pain.

- Studies show that ACC activation correlates with subjective pain unpleasantness, even when the physical intensity of pain is constant (Rainville et al., 1997).

- The ACC is richly interconnected with limbic (amygdala, hippocampus), cognitive (prefrontal cortex), and motor systems, enabling it to integrate affective, attentional, and behavioral responses to pain (Shackman et al., 2011).

- The ACC is involved in pain anticipation, which can amplify emotional distress even before the pain occurs (Koyama et al., 2005).

- Chronic pain patients often show structural and functional changes in the ACC, suggesting a maladaptive feedback loop that reinforces pain-related suffering (Baliki et al., 2006).

Thus, the ACC is not responsible for detecting pain, but for how unpleasant and distressing it feels, and for driving the motivational state to take action.

3. Limbic Modulation and Homeostasis

Leknes & Tracey (2008) propose a framework for understanding how pain and pleasure share overlapping neurobiological systems, particularly in limbic circuits. They note that context, expectation, and emotional state can either amplify or dampen pain via top-down modulation of limbic and brainstem structures.

- The ACC and amygdala are sensitive to emotional reappraisal, social support, and placebo analgesia, demonstrating that the emotional meaning of pain can drastically change the experience (Wager et al., 2004).

- Pain that is interpreted as meaningful or self-chosen (e.g., in rituals or athletic endurance) can be experienced as less unpleasant, implicating limbic regulation of pain perception (Leknes & Tracey, 2008).

This suggests that the limbic system is central in determining whether pain is perceived as threatening and intolerable or manageable and meaningful.

4. Summary of Functional Roles

| Region | Role in Pain Processing |

| Amygdala | Assigns emotional salience; fear, anxiety, memory of pain; enhances pain when perceived as threatening. |

| ACC | Encodes pain unpleasantness; mediates suffering, motivation to escape pain; modulated by expectation, attention, and emotional context. |

Clinical Relevance

- Chronic pain syndromes (e.g., fibromyalgia, neuropathic pain) often involve heightened activity in the amygdala and ACC, contributing to emotional suffering, catastrophizing, and avoidance behavior (Hashmi et al., 2013).

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness, and biofeedback target these limbic circuits to reframe pain perception, reduce suffering, and restore functional coping.

- The limbic-emotional dimension of pain underscores the importance of holistic and biopsychosocial models in treatment.

References:

Apkarian, A. V., Bushnell, M. C., Treede, R. D., & Zubieta, J. K. (2005). Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. European Journal of Pain, 9(4), 463–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001

Baliki, M. N., Geha, P. Y., Apkarian, A. V., & Chialvo, D. R. (2006). Beyond feeling: chronic pain hurts the brain, disrupting the default-mode network dynamics. Journal of Neuroscience, 28(6), 1398–1403. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4123-07.2008

Cleveland Clinic. (2024). Limbic system: What it is, function, parts & location [Illustration]. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/limbic-system

Hashmi, J. A., Baliki, M. N., Huang, L., Baria, A. T., Torbey, S., Hermann, K. M., … & Apkarian, A. V. (2013). Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain, 136(9), 2751–2768. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt211

Koyama, T., McHaffie, J. G., Laurienti, P. J., & Coghill, R. C. (2005). The subjective experience of pain: Where expectations become reality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(36), 12950–12955. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0408576102

Leknes, S., & Tracey, I. (2008). A common neurobiology for pain and pleasure. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(4), 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2333

Neugebauer, V., Galhardo, V., Maione, S., & Mackey, S. C. (2009). Forebrain pain mechanisms. Brain Research Reviews, 60(1), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.014

Rainville, P., Duncan, G. H., Price, D. D., Carrier, B., & Bushnell, M. C. (1997). Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science, 277(5328), 968–971. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5328.968

Shackman, A. J., Salomons, T. V., Slagter, H. A., Fox, A. S., Winter, J. J., & Davidson, R. J. (2011). The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(3), 154–167. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2994

Simons, L. E., Elman, I., & Borsook, D. (2014). Psychological processing in chronic pain: a neural systems approach. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 39, 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.12.006

Wager, T. D., Rilling, J. K., Smith, E. E., Sokolik, A., Casey, K. L., Davidson, R. J., … & Cohen, J. D. (2004). Placebo-induced changes in FMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science, 303(5661), 1162–1167. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1093065