A Journey Through Many Paths

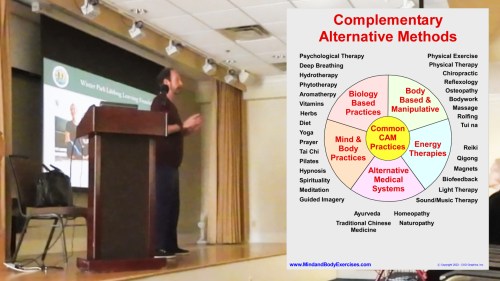

In my book, Spiritual Enlightenment Across Traditions: Teachings from the Lineage of the Warrior, Scholar and Sage, I share the insights I’ve gathered over more than four decades of walking a path that weaves together holistic health, martial arts, and spiritual philosophy. This work is both deeply personal and broadly comparative, a look at how different cultures and traditions have understood and lived the experience we call “enlightenment.”

Why I Wrote This Book

I’ve met many seekers, teachers, and wanderers on this road. I’ve seen genuine awakening and I’ve also seen premature or false claims of it. I wanted to write something that cuts through the noise, honoring the diversity of spiritual traditions while pointing to the shared essence they all reflect: a transformation beyond ego, a liberation from suffering, and a deepening of compassion.

What Enlightenment Means to Me

For me, enlightenment is not an abstract ideal. It is an intimate shift in how we see and engage with life. A moment when the boundaries of the self dissolve, and we know, not as an idea but as a direct experience, that we are inseparable from the whole. Buddhists call it emptiness; Christians call it union with God; Sufis call it the annihilation of self in the Divine; Hindus call it self-realization. These words may differ, but the lived reality they point to is strikingly similar.

Traveling Through Many Traditions

In this book, I explore enlightenment as it’s understood in:

- Buddhism — from the discipline of Theravāda to the spontaneous recognition of Dzogchen to achieve nirvana.

- Hinduism — devotion, self-inquiry, and the pursuit of liberation (moksha).

- Christianity — theosis, spiritual marriage, and the mystics’ union with God.

- Sufism — the journey through fanā’ into baqā’, dying to the ego and living in the Divine.

- Judaism and other mystical traditions — where awakening is as much about ethical living as it is about inner vision.

I also reflect on contemporary teachers, such as Ramana Maharshi, Jiddu Krishnamurti, Eckhart Tolle, who frame enlightenment in ways that make sense in today’s secular, globalized world.

The Question of Authenticity

Over the years, I’ve learned that authentic awakening requires more than self-claim. In many traditions, enlightenment is confirmed through lineage, acknowledged by respected teachers, and recognized by a community, not only for mystical insight but for how a person lives. Humility, compassion, and ethical conduct are the truest signs. Without them, even the most dazzling “spiritual experiences” can be little more than ego in disguise.

Enlightenment in Daily Life

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned is that enlightenment isn’t about escaping the world. It’s about engaging with it more fully. Zen calls it “returning to the marketplace.” Hinduism calls it lokasangraha or working for the welfare of the world. In my own life, this has meant teaching, serving, and trying to embody what I have learned, not just in meditation halls, but in everyday interactions.

A Unique Practice: Chamsa Meditation

In my exploration, I also share Chamsa meditation, a Korean-Taoist practice that blends Taoist inner alchemy, Seon Buddhism, and Korean shamanic elements. It’s a stage-based method of self-inquiry that dissolves identity and returns awareness to its original, formless nature. To me, it’s a living example of how traditions can blend to create powerful paths to awakening.

Awakening as a Lifelong Journey

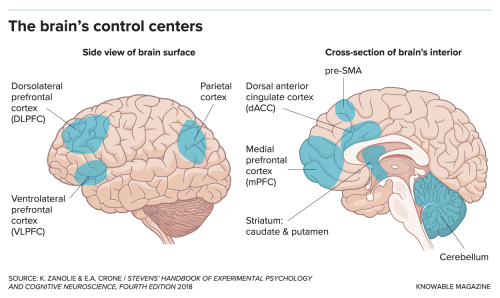

Some people think enlightenment is a single, dramatic moment. My experience and the testimony of many traditions says otherwise. Awakening deepens over time. Insight grows. Compassion expands. And presence becomes more natural. Even science is beginning to confirm this: neuroscience now observes brain changes in long-term meditators, hinting at a bridge between spiritual experience and measurable transformation.

An Invitation to Seekers

I wrote this book to serve as both a map and a mirror. It offers a map of the many authentic paths, and a mirror to help you see where you are on your own.

My advice is simple:

- Commit to your practice.

- Seek authentic teachers and communities.

- Be patient, as real transformation takes time.

- Live your insights in the world, not just in private.

In the end, enlightenment is not about becoming something extraordinary.

It’s about becoming fully human, being present, compassionate, and free in this very life, wherever you are. I believe it’s possible for anyone who walks the path with sincerity, discipline, and an open heart.