In today’s fast-paced world, stress-related conditions are on the rise. Autogenic therapy, also known as autogenic training, offers a powerful way to counterbalance modern stress through a simple, structured set of mental exercises. Developed by German psychiatrist Johannes Heinrich Schultz and coined the term in 1928, this self-regulation technique continues to help people worldwide regain calm, reduce anxiety, and improve overall well-being.

What Is Autogenic Therapy?

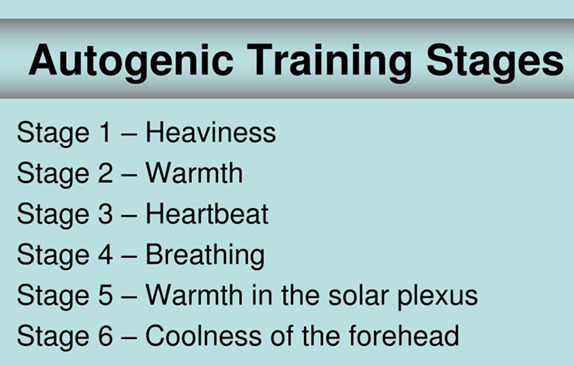

Autogenic therapy is a relaxation technique that uses self-suggestions to bring about physical and emotional calmness. The practice involves six standardized exercises focusing on sensations like:

- Heaviness and lightness in the limbs

- Warmth

- Heartbeat regulation

- Breathing awareness

- Abdominal warmth

- Forehead cooling (Luthe & Schultz, 1969)

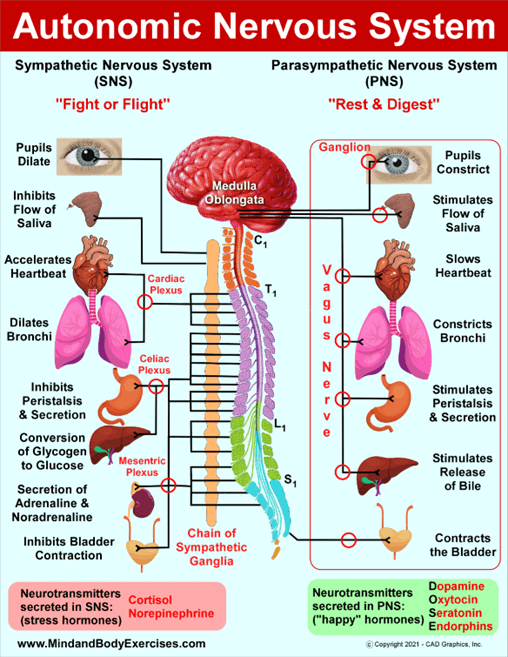

These exercises promote a shift in the autonomic nervous system toward the parasympathetic or “rest and digest” mode, reducing the physiological effects of stress.

Although not usually classified as meditation, autogenic therapy shares similar traits with meditative and mindfulness-based practices:

- Present-moment awareness

- Regulation of breath and heart rate

- Promotion of internal balance and nervous system calm (Melnikov, 2021)

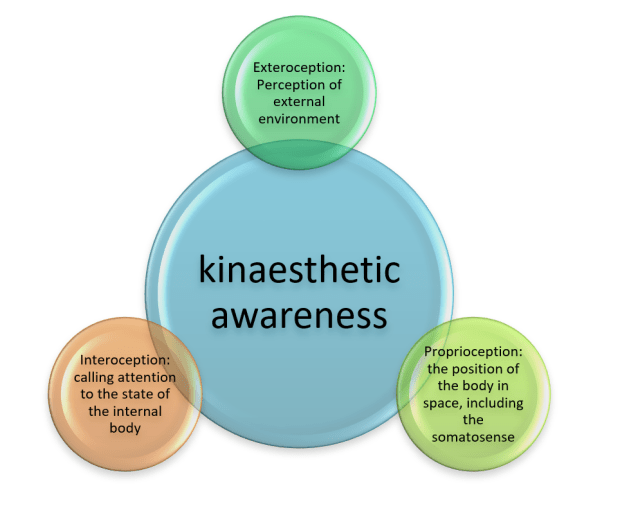

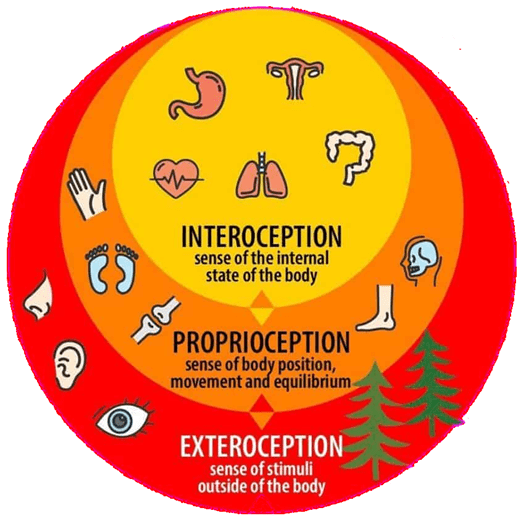

A Shared Language: Body Awareness in Mind–Body Disciplines

What’s especially fascinating is that autogenic therapy aligns with ancient mind–body traditions found in:

- Tai Chi

- Qigong

- Yoga

- Martial Arts

These disciplines often guide practitioners to cultivate bodily sensations that echo those used in autogenic training:

- Feelings of lightness or heaviness in the limbs

- Generating internal warmth (often associated with breath or energy flow)

- Focusing on the heartbeat or breath rhythm

- Stimulating abdominal heat (known in some traditions as dantian activation)

- Creating a sense of coolness or spaciousness in the head or forehead

These parallels suggest that human self-regulation, through structured inner awareness, is a timeless and cross-cultural approach to stress relief, energy balance, and health.

Benefits of Autogenic Training

When practiced consistently, autogenic therapy has been shown to:

- Reduce anxiety and stress

- Improve sleep quality

- Lower blood pressure

- Enhance emotional and nervous system resilience

- Relieve headaches, muscle tension, and chronic fatigue (Stetter & Kupper, 2002)

Its simplicity and accessibility make it a popular choice for those looking for holistic, non-invasive ways to manage daily pressures and improve health.

How It Works

Each autogenic session involves repeating mental phrases such as, “my arms are heavy and warm,” while reclining or sitting in a quiet space. The mind’s focus on these specific body cues leads to a measurable shift in physiology, lowering stress hormones, heart rate, and muscle tension (Luthe & Schultz, 1969; Stetter & Kupper, 2002).

Many people practice autogenic training independently, with audio guidance, or under the supervision of a certified therapist.

⚠️ Caution: Autogenic Training and Psychotic Disorders

While autogenic therapy is safe for most individuals, it may not be appropriate for people with psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder with psychotic features (Fletcher, 2023. Here’s why:

1. Exacerbation of Symptoms

The use of self-suggestion and imagery can potentially worsen hallucinations or delusional thinking in vulnerable individuals (Kanji, 2006; Stetter & Kupper, 2002).

2. Potential for Dissociation

The deep relaxation states achieved may induce altered consciousness or dissociation, which can be unsettling or unsafe for those with psychotic tendencies.

3. Difficulty in Reality Testing

Psychotic conditions often impair one’s ability to distinguish between internal experience and external reality. Autogenic training might blur these lines further (Stetter & Kupper, 2002).

4. Medication Disruption Risk

Some individuals may believe that relaxation practices can replace essential medication, potentially leading to non-compliance and relapses (Mueser & Jeste, 2008).

Because of these risks, it’s essential that individuals with psychotic disorders engage in any form of relaxation training only under professional medical supervision. More recent research has suggested that autogenic therapy may actually help those suffering from schizophrenia (Breznoscakova et al., 2023).

Final Thoughts

Autogenic therapy offers a safe, evidence-based, and self-directed method to reduce stress and promote relaxation. Its emphasis on internal sensations such as warmth, breath, heartbeat, and mental stillness, places it in harmony with long-standing Eastern practices like tai chi, yoga, and qigong.

For most people, autogenic therapy can serve as a cornerstone of a healthy lifestyle, but those with complex mental health conditions should consult with trained professionals to ensure it is suitable.

References:

Breznoscakova, D., Kovanicova, M., Sedlakova, E., & Pallayova, M. (2023). Autogenic Training in Mental Disorders: What Can We Expect? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4344. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054344

Fletcher, J. (2023, August 17). Autogenic training: Benefits, limitations, and how to do it. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/autogenic-training#how-to-do-it

Luthe, W., & Schultz, J. H. (1969). Autogenic therapy (Vol. 1–6). New York: Grune & Stratton.

Mueser, K. T., & Jeste, D. V. (2008). Clinical handbook of schizophrenia. New York: Guilford Press.

Melnikov, M. Y. (2021). The Current Evidence Levels for Biofeedback and Neurofeedback Interventions in Treating Depression: A Narrative review. Neural Plasticity, 2021, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8878857

Stetter, F., & Kupper, S. (2002). Autogenic training: a meta-analysis of clinical outcome studies. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 27(1), 45–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014576505223

VA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. (n.d.). AUTOGENIC TRAINING. In VA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (pp. 1–3). https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/docs/Autogenic-Training.pdf

I teach and offer lectures about holistic health, physical fitness, stress management, human behavior, meditation, phytotherapy (herbs), music for healing, self-massage (acupressure), Daoyin (yoga), qigong, tai chi, and baguazhang.

Please contact me if you, your business, organization, or group, might be interested in hosting me to speak on a wide spectrum of topics relative to better health, fitness, and well-being.

I look forward to further sharing more of my message by partnering with hospitals, wellness centers, VA centers, schools on all levels, businesses, and individuals who see the value in building a stronger nation through building a healthier population.

I also have hundreds of FREE education video classes, lectures, and seminars available on my YouTube channel at:

https://www.youtube.com/c/MindandBodyExercises

Many of my publications can be found on Amazon at:

http://www.Amazon.com/author/jimmoltzan

My holistic health blog is available at:

https://mindandbodyexercises.wordpress.com/

http://www.MindAndBodyExercises.com

Mind and Body Exercises on Google: https://posts.gle/aD47Qo

Jim Moltzan

407-234-0119