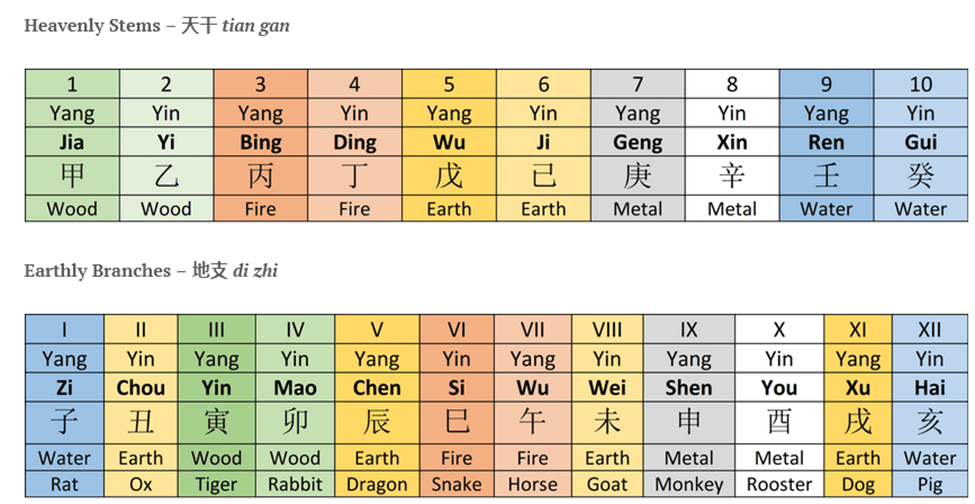

In Chinese and Korean astrology and traditional cosmology, time is conceptualized as cyclical and governed by natural forces. These systems are used in saju analysis, geomancy, and ritual calendars. Two fundamental components of this worldview are:

- The 10 Heavenly Stems (Tian Gan – Chinese), Cheon‑gan – Korean)

- The 12 Earthly Branches (Di Zhi– Chinese), (Ji‑ji – Korean)

Together with the Five Elements (Wuxing) and Yin – Yang duality, they create a sexagenary (60-day) cycle that is the basis for identifying auspicious days and mapping personal fate (Lee, 1981).

Part 1: The 10 Heavenly Stems (Cheon‑gan)

The Heavenly Stems are a 10-day cycle derived from the Five Elements:

- Wood (木) – Spring

- Fire (火) – Summer

- Earth (土) – Transition

- Metal (金) – Autumn

- Water (水) – Winter

Each element has a Yang (active) and Yin (receptive) form, yielding 10 total stems (Yoon, 2017).

These stems are associated with cardinal directions and form the energetic “climate” of each day:

Korean version of the 10 Heavenly Stems (Cheon‑gan)

| Number | Stem | Element | Polarity | Direction |

| 1 | 갑 (Gap) | Wood | Yang | East |

| 2 | 을 (Eul) | Wood | Yin | East |

| 3 | 병 (Byeong) | Fire | Yang | South |

| 4 | 정 (Jeong) | Fire | Yin | South |

| 5 | 무 (Mu) | Earth | Yang | Center |

| 6 | 기 (Gi) | Earth | Yin | Center |

| 7 | 경 (Gyeong) | Metal | Yang | West |

| 8 | 신 (Sin) | Metal | Yin | West |

| 9 | 임 (Im) | Water | Yang | North |

| 10 | 계 (Gye) | Water | Yin | North |

These rotating influences affect feng shui, health, and calendar-based rituals (Wu, 2005)

Part 2: The 12 Earthly Branches (Ji‑ji)

The Earthly Branches create a 12-day cycle and are symbolized by the 12 zodiac animals. Each branch has corresponding elemental, directional, and seasonal meanings.

Korean version of the 12 Earthly Branches (Di Zhi)

| Branch | Animal | Element | Direction |

| 자 (Ja) | Rat | Water | North |

| 축 (Chuk) | Ox | Earth | NNE |

| 인 (In) | Tiger | Wood | NE |

| 묘 (Myo) | Rabbit | Wood | East |

| 진 (Jin) | Dragon | Earth | ESE |

| 사 (Sa) | Snake | Fire | SE |

| 오 (O) | Horse | Fire | South |

| 미 (Mi) | Goat | Earth | SSW |

| 신 (Sin) | Monkey | Metal | SW |

| 유 (Yu) | Rooster | Metal | West |

| 술 (Sul) | Dog | Earth | WNW |

| 해 (Hae) | Pig | Water | NW |

Each day of the lunar month has an assigned branch, and this is one way that daily energy is determined (Kim, 2018).

Part 3: The 60-Day Cycle (Yukship Gapja)

Because 10 and 12 have a least common multiple of 60, this pairing forms a cosmological sequence that completes once every 60 days or years, depending on the calendar scale (Lee, 1981).

This cycle underlies:

- Daily calendar rotation

- 60-year birthday celebrations

- Spiritual timing for rituals and divination

The 60 units are viewed as elementally distinct days, each with specific fortune or taboo status.

Part 4: Special Days in Korean Mystical Practice

1. Sonnal – Unlucky Days

Rather than being “auspicious,” these are dangerous or unlucky days, often tied to folk shamanic beliefs. They are days when:

- One should not cut hair or nails

- Surgery or travel is discouraged

- Avoid beginning manual tasks with construction, cutting, repairs, etc.

- Spirit intrusion is considered high (Kim, 2018)

2. Gil-il – Lucky Days

These are selected based on:

- Stem–branch harmony (Heavenly Stem supports the Earthly Branch)

- Lack of elemental conflict with the person’s saju chart

- Favorable directional flow based on geomantic readings (Yoon, 2017)

In rural traditions, agricultural festivals or ancestral rites are often aligned with these dates. These are perceived as the best days for weddings, moving into a house, starting businesses, making kimchi, conceiving a child.

3. December as Auspicious?

There is some belief that the lunar month aligned with Rat (Ja-wol), roughly December in the Gregorian calendar is energetically potent, because:

- It is the start of the solar calendar (dongji, or winter solstice, marks the return of yang energy)

- It represents fertility and rebirth in seasonal logic (Wu, 2005)

However, no universal doctrine marks December as always auspicious; it depends on the year’s alignment and individual energy patterns.

Part 5: Application in Korean Spiritual Life

- Saju-palja: Four Pillars of Destiny combines year, month, day, and hour to forecast character, fate, and life timing. Each pillar has a stem–branch combination.

- Pungsu-jiri: Korean geomancy uses directional alignments of time and space based on these cycles, to site homes, graves, and sacred spaces (Yoon, 2017).

- Almanac Use: Traditional Korean almanacs list each day’s stem–branch, auspicious tasks, and prohibitions.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is not to judge or critique these particular belief systems, but rather offer information on differing perspectives. The integration of Heavenly Stems, Earthly Branches, Five Elements, and Yin-Yang philosophy produces a deeply symbolic and cyclical framework for interpreting time in Korean mysticism. Whether identifying auspicious dates, planning ancestral rites, or decoding one’s destiny, these systems offer a structured metaphysical map of existence. Understanding them opens a window into a worldview where time, space, and spirit are intimately connected.

References

Heavenly stems and earthly branches. (n.d.). https://www.hko.gov.hk/en/gts/time/stemsandbranches.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Kim, C. (2018). Korean shamanism. In Routledge eBooks. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315198156

Lee, J. Y. (1981). Korean Shamanistic rituals. In Leo Laeyendecker & Jacques Waardenburg (Eds.), Religion and Society (Vol. 12). Mouton Publishers. https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9783110811377_A33483020/preview-9783110811377_A33483020.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Yoon, H. (Ed.). (2017). P’ungsu: A Study of Geomancy in Korea. State University of New York Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.18254509

Wu, S. (2005). Chinese Astrology: Exploring the Eastern Zodiac. Tuttle Publishing. https://archive.org/details/chineseastrology0000wush