Understanding the Closed High-Control Environment

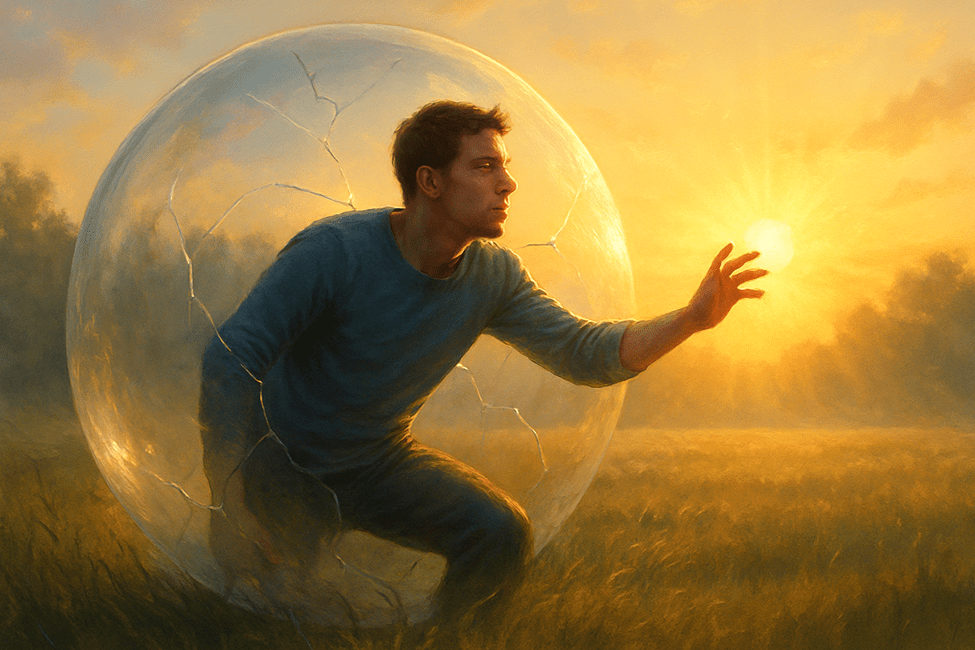

Working, playing, living, and existing in a high-control environment, whether ideological, organizational, or social, is analogous to living within a bubble. The bubble becomes both a boundary and a lens: it filters what individuals perceive as reality, limiting awareness of the outside world while reinforcing the values, language, and narratives within. Over time, the self becomes entangled with the group identity, and what is seen through the bubble’s translucent membrane feels complete, even if it is only a fragment of reality.

This essay explores the mechanisms that create such a bubble, how it maintains psychological and social control, and why emerging from it is a gradual and deeply transformative process that can take years to complete, if at all.

Formation of the Bubble: Structure and Psychology

The “bubble” metaphor aptly describes the environment of high-control systems, whether religious, corporate, political, or familial. Sociologist Janja Lalich (2004) identified this as a “bounded choice” system or an environment where individuals feel they are exercising free will, yet their decisions are constrained by an intricate web of ideology, social pressure, and authority. The boundaries of the bubble are maintained through charismatic authority, a closed belief system, and control of behavior and information (Lalich, 2004).

People often join or remain within such systems because they fulfill psychological needs for certainty, belonging, and meaning (Manstead, 2018). According to social identity theory, group membership provides emotional security and self-esteem, particularly in times of uncertainty or perceived chaos (Hogg, 2014). Within the bubble, structure and purpose replace ambiguity, creating a sense of safety that paradoxically relies on conformity.

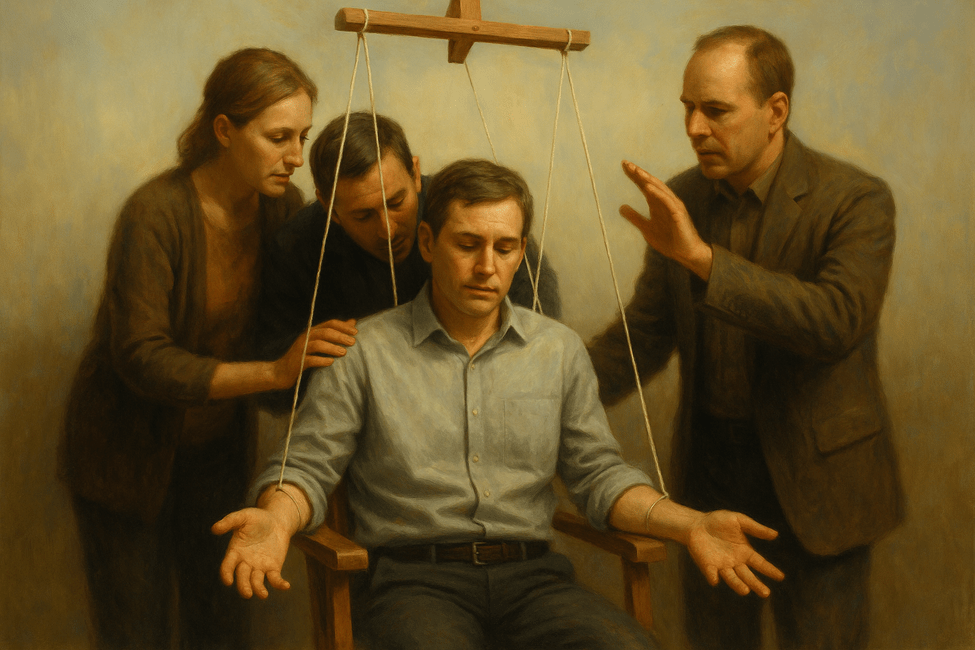

In practical terms, the bubble’s formation relies on several mechanisms:

- Restricted external input – information from outside the group is censored or reframed to align with internal narratives (Bai et al., 2025).

- Filtered internal discourse – members adopt specialized language and redefinitions that shape thought patterns.

- Identity fusion – personal identity merges with the group, making independent thought feel like betrayal (Swann et al., 2012).

- Dependence on internal validation -acceptance, approval, and purpose come exclusively from within the system.

Thus, the bubble becomes self-reinforcing: the more one participates, the stronger its walls become, and the more alien the outside world appears.

Dynamics Within the Bubble

Once established, the bubble governs perception, behavior, and emotion.

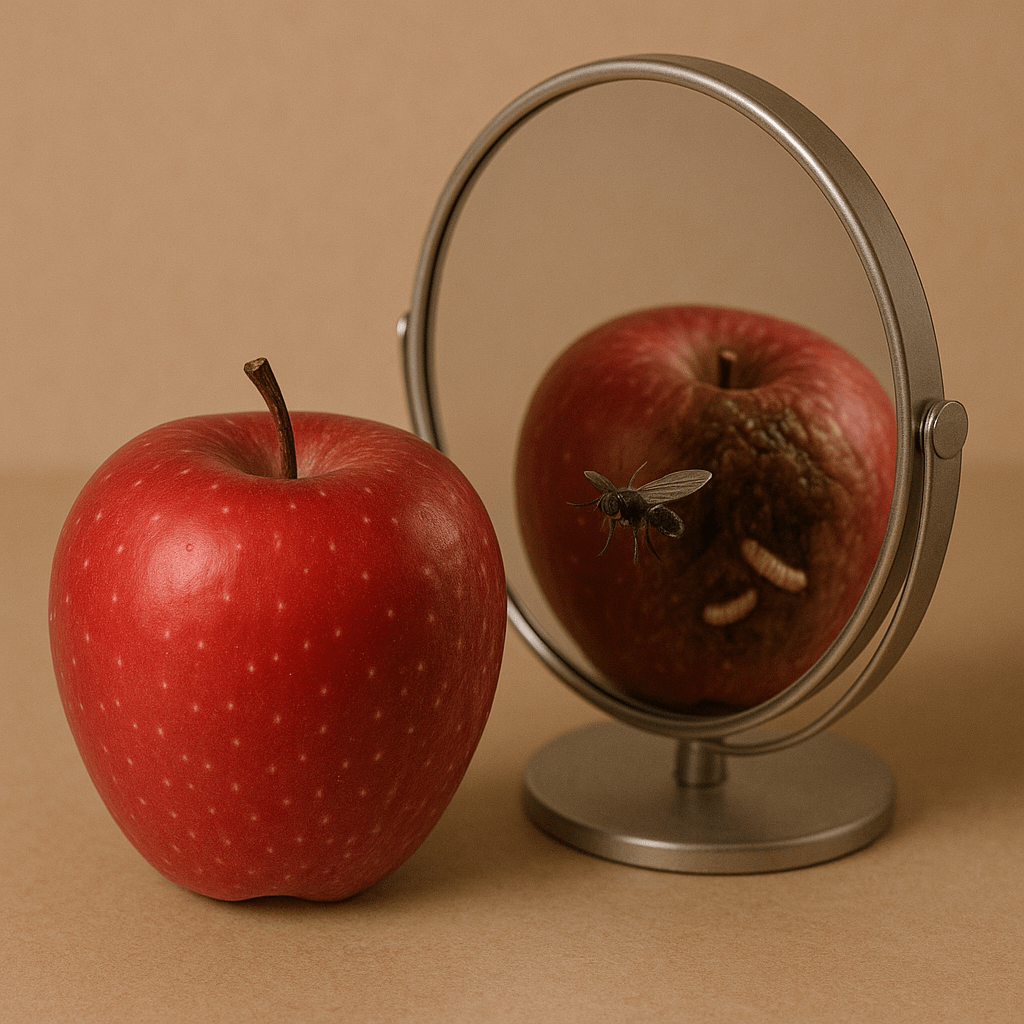

- Cognitive and Perceptual Narrowing

Members of high-control systems experience epistemic closure, meaning alternative viewpoints are systematically excluded (Lalich, 2004). Research on “identity bubble reinforcement” confirms that repetitive exposure to uniform perspectives narrows the ability to evaluate or accept new information (Bai et al., 2025). The mind begins to interpret all experience through the group’s ideology, a phenomenon sometimes called cognitive confinement.

2. Behavioral Regulation

Rules, rituals, and social hierarchies become omnipresent. Even leisure and play serve the system’s goals. Studies of humans in isolated or closed environments such as military units or analog space missions show how confinement fosters conformity and peer surveillance while diminishing autonomy and spontaneity (Landon et al., 2024). Similarly, within social or ideological bubbles, behavior is subtly or overtly regulated by reward, shame, and collective pressure.

3. Emotional Conditioning and Identity Fusion

The bubble shapes emotional experience as well. Joy, guilt, pride, and fear become linked to compliance and performance. Identity fusion is a deep merging of personal and group identity that creates extreme loyalty and self-sacrifice (Swann et al., 2012). Members may feel love for their peers yet fear ostracism for deviation. Over time, the bubble is no longer just an environment, but rather it becomes a psychological home.

4. Living Entirely Inside the Bubble

When one’s workplace, social life, belief system, and home all exist within the same controlled sphere, the boundary between personal and institutional identity collapses. The person’s worldview becomes totalistic. Every event, thought, or external challenge is interpreted through the bubble’s lens, reducing the ability to recognize manipulation or control (Lalich, 2004). What lies beyond becomes shadowy, threatening, or meaningless.

Emerging from the Bubble: A Long-Term Process of Deconditioning

- The Initial Awakening

Awakening begins when cognitive dissonance cracks the bubble, through a contradiction, a loss of trust, or an encounter with external perspectives. Yet recognition alone rarely results in immediate liberation. As Lalich (2004) notes, even when individuals want to leave, “the system of meaning remains deeply internalized.” Awareness of the bubble does not dissolve it overnight; it simply begins the process of slowly deflating its illusions.

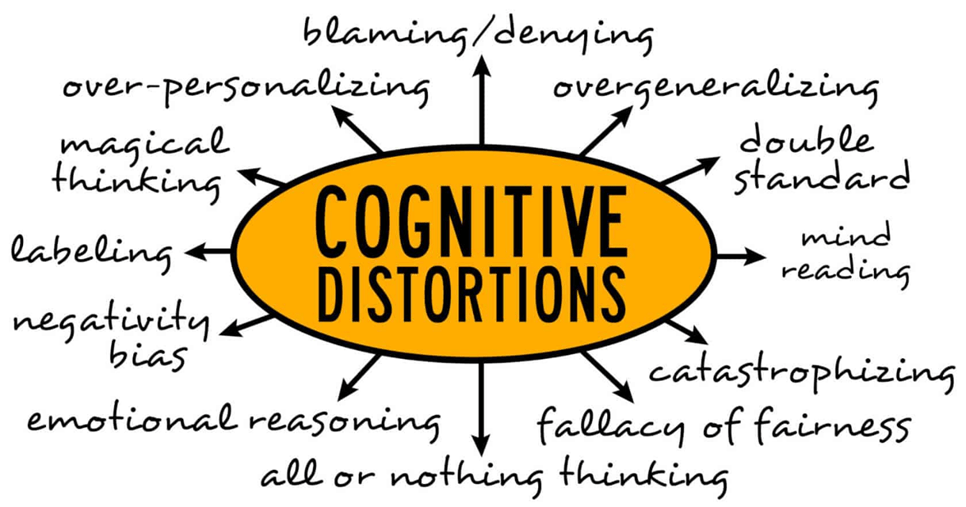

2. De-identification and Cognitive Reconstruction

The journey out of the bubble is not instantaneous. It is rarely a matter of days, weeks, or even months, but rather a multi-year process of rebuilding perception and selfhood. Research on post-cult recovery and identity reconstruction shows that the internal belief structures and emotional dependencies cultivated within such systems can persist for years (Langone, 2017). The mind must unlearn distorted thinking, while the nervous system recalibrates to tolerate ambiguity, autonomy, and uncertainty.

In psychological terms, this is a deconditioning process, or a gradual dismantling of internalized norms, often accompanied by grief, anger, and disorientation (Lalich, 2004). Even when one consciously chooses to “step outside,” subconscious habits of thought and emotional triggers may continue to pull them back toward the familiar confines of the bubble.

3. Emotional Healing and Re-socialization

Leaving the bubble involves emotional recovery as much as cognitive change. Isolation, fear, and identity loss are common. Former members often report difficulty trusting others, setting boundaries, or believing in their own judgment (Langone, 2017). Longitudinal studies of people emerging from high-control settings, such as isolated work bubbles or pandemic quarantine environments, show increased depression and anxiety due to disrupted social rhythms and restricted autonomy (Ely, 2023). The process of re-socialization requires patience, self-compassion, and often therapeutic support.

4. Integration and Perspective

Much like a person standing too close to a tree, those living within the bubble cannot see the whole of what surrounds them. When one’s view is pressed against the trunk, the details of bark, leaves, and branches may be clear, yet the entirety of the tree in its height, shape, and place within the forest, remains unseen. Only by stepping back and gaining distance can the full form come into view. Similarly, only by separating from the bubble can individuals begin to perceive the true scope of their environment and the reality that extends beyond it.

True recovery occurs when one learns to live outside the bubble without recreating its patterns elsewhere. This means cultivating critical thinking, autonomy, and a tolerance for complexity. As Lalich (2004) emphasizes, liberation is not merely external but internal. Freedom is achieved when the bounded choice system no longer defines one’s reality.

The individual must relearn to see the world directly, rather than through the distortive lens of collective ideology. This reintegration phase may take years of ongoing reflection, self-education, and experiential contrast with broader society. It represents a journey toward authenticity, where perception aligns with lived experience rather than imposed belief.

Conclusion

Living within a high-control environment is akin to existing inside a sealed bubble that dictates one’s thoughts, behaviors, and emotional reality. The bubble offers structure, belonging, and certainty but at the cost of autonomy and authentic perception. To truly see beyond it requires more than desire. It demands time, courage, and sustained self-work.

Emerging from such confinement is a long-term metamorphosis, not a quick awakening. One must slowly deconstruct internalized narratives, rebuild personal agency, and re-establish connection with a broader, more ambiguous world. Only through this extended process can individuals reclaim their full humanity and rediscover life beyond the bubble’s transparent walls.

Appendix A

Key Psychological and Sociological Terms

Autonomy.

The ability to think, decide, and act independently based on one’s own values and reasoning rather than imposed authority or group pressure (Manstead, 2018; Lalich, 2004).

Bounded Choice.

A term introduced by Janja Lalich (2004) to describe a system in which individuals appear to exercise free will, but their decisions are constrained by the group’s ideology, social structure, and internalized control mechanisms (Lalich, 2004).

Cognitive Confinement (Epistemic Closure).

A restriction of thought and perception in which alternative ideas are dismissed, and information is filtered through a rigid belief system, limiting one’s ability to view reality objectively (Bai et al., 2025; Lalich, 2004).

Cognitive Dissonance.

A psychological state of discomfort experienced when one’s beliefs, values, or actions conflict with one another, often leading to rationalization or justification to reduce internal tension (Rashiti, 2021).

De-identification.

The process of separating one’s personal identity from that of the controlling group or ideology that once defined it, often accompanied by confusion and emotional struggle (Langone, 2017).

Deconditioning.

The gradual process of unlearning habits, beliefs, and conditioned responses that were instilled by an authoritarian or high-control system (Lalich, 2004; Langone, 2017).

Emotional Conditioning.

The learned association of specific emotional responses—such as guilt, shame, fear, or pride—with compliance or disobedience to group norms (Langone, 2017).

Identity Fusion.

A psychological phenomenon where personal and group identities merge, creating strong emotional bonds and a willingness to prioritize the group over oneself (Swann et al., 2012).

Identity Reconstruction.

The rebuilding of an authentic, self-defined identity following departure from a high-control environment; involves reflection, self-awareness, and integration into a broader worldview (Langone, 2017).

Internalized Control.

A condition in which external authority or group expectations become self-enforced, causing individuals to monitor and regulate their own thoughts and behaviors according to imposed standards (Lalich, 2004).

Psychological Homeostasis.

The mind’s effort to maintain internal emotional stability. When disrupted—such as during deconstruction of old belief systems—temporary imbalance may occur before a new equilibrium forms (Manstead, 2018).

Re-socialization.

The process of relearning social norms, boundaries, and interpersonal trust after leaving a closed or controlling environment (Langone, 2017; Ely et al., 2023).

Social Identity Theory.

A framework that explains how individuals derive self-concept and meaning from group membership, promoting cohesion but also conformity and in-group bias (Hogg, 2014).

References:

Bai, X., Lian, S., Sun, X., & Niu, G. (2025). The relationship between information hoarding and selective exposure: The role of information overload, identity bubble reinforcement, and intolerance of uncertainty. BMC Psychology, 13(736). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-03062-8

Ely, G., Woodman, T., Roberts, R., Jones, E., Wedatilake, T., Sanders, P., & Peirce, N. (2023). The impact of living in a bio-secure bubble on mental health: An examination in elite cricket. Psychology of sport and exercise, 68, 102447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102447

Hogg, M. A. (2014). From Uncertainty to Extremism: Social Categorization and Identity Processes: Social Categorization and Identity Processes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(5), 338-342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414540168

Lalich, J. (2004). Bounded ChoiceTrue believers and charismatic cults. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520231948.001.0001

Landon, L. B., Miller, J. C. W., Bell, S. T., & Roma, P. G. (2024). When people start getting real: The Group Living Skills Survey for extreme work environments. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1348119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1348119

Langone, M. D. (2017). Recovery from cults: Help for victims of psychological and spiritual abuse. American Family Foundation Press.

Manstead, A. S. R. (2018). The psychology of social class: How socio-economic status influences identity, cognition, behaviour and health. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57(2), 267–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12251

Rashiti, V. (2021, August 19). What are cognitive distortions and what to do about them? Youth Time Magazine: News That Inspires, Updates That Matter. https://youthtimemag.com/what-are-cognitive-distortions-and-what-to-do-about-them/

Swann, W. B., Jr., Gómez, Á., Seyle, D. C., Morales, J. F., & Huici, C. (2012). Identity fusion: The interplay of personal and social identities in extreme group behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 995–1011. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013668