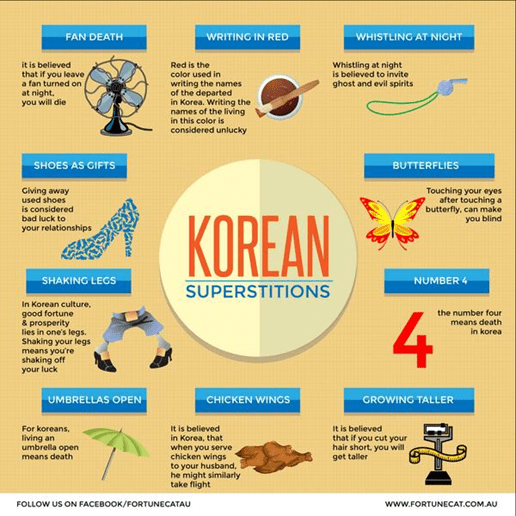

Every culture has its own set of superstitions, or unwritten rules and quiet rituals that shape daily habits and social behavior. In Korea, these beliefs reflect a blend of Shamanism, Confucian ethics, Buddhism, and folk wisdom, passed down through generations. While some appear quirky to outsiders, they often carry symbolic meaning, revealing how Koreans have historically sought to maintain harmony with ancestors, nature, and unseen forces. I was first introduced to many of these rules through my firsthand experiences within my Korean martial arts lineage many decades ago. Some of these rituals were fairly open and on display to students, whereas others were taught only to higher ranking students and instructors (too much culture shock for some I guess). Whether these rituals were relative to martial arts training, is a discussion for another day. However, I was exposed to some different aspects of Korean superstitions, which have helped me to expand my understanding of Eastern cultures.

This article explores a wide collection of Korean superstitions, ranging from everyday habits to ritual practices, while unpacking their origins and cultural significance. These are based upon my own personal communications of folklore” or “unpublished oral traditions” that I draw from my field knowledge and/or community memory.

Death and the Spirit World

Writing Names in Red Ink

In Korea, writing a living person’s name in red is taboo. Red ink was traditionally reserved for death registers and tomb inscriptions, marking separation from the living. To this day, writing someone’s name in red is thought to invite misfortune.

Chopsticks Upright in Rice

Placing chopsticks vertically in a bowl of rice mimics ancestral death offerings made during rituals (jesa). Doing this at the table is considered deeply disrespectful and ominous.

Fan Death

One of Korea’s most famous modern beliefs is that sleeping in a closed room with an electric fan can cause death by suffocation or hypothermia. Popularized in the 1970s during energy-saving campaigns, this superstition persists even today, many fans sold in Korea include auto-off timers (Reuters, 2007).

Broken Mirrors

A broken mirror is considered dangerous. In older traditions, the edges were coated with dog feces and then discarded into running water. Mirrors were believed to act as portals; this ritual sealed the gateway and washed misfortune away.

Salt After Funerals

Throwing salt over one’s shoulders and toward the east, after attending a funeral purifies and prevents lingering spirits from following home. The east, symbolizing sunrise, represents life and renewal.

Salting a Room

Another ritual purification involves sprinkling salt around the perimeter of a room, especially in the corners where spirits are believed to hide. Salt is a powerful purifier in Korean Shamanism, banishing negativity and restoring balance.

Numbers, Dates, and Direction

The Number Four

The word “four” sounds like death (sa) in Sino-Korean pronunciation. As a result, hospitals and apartments may skip the 4th floor or label it “F”

Moving on Inauspicious Days

Before moving house or opening a business, many families consult a fortune teller(saju) or lunar calendar to avoid unlucky dates.

“Nail Days”

A lesser-known belief uses the calendar, where a folk astrological system is tied to geomantic principles. Count two days for each cardinal direction, and the ninth day is auspicious for beginning projects, conceiving children, or planting crops. The “nail” refers to construction of whatever project.

Bed Facing North

In Korean funerary customs, the deceased are laid with their heads pointing north. For this reason, it is considered inauspicious to sleep with the head of the bed in that direction.

Right Foot First

Stepping into a new building with the right foot ensures luck and prosperity, symbolically “putting your best foot forward.”

Man Entering First on the First Day of the Month

On the first of the month, it is considered good fortune if a man enters a home or business first, reflecting the auspicious, initiating power of yang energy.

Don’t Cut Corners

Try not to pass or hand objects over a corner of desk or table, so as not to bring bad luck by “cutting corners.”

Food and Household Rituals

Whistling at Night

Whistling in the dark is said to attract snakes or wandering spirits. In Shamanic belief, sound could summon unseen entities.

Giving Shoes as a Gift

Shoes symbolize departure, so gifting them may cause the recipient to “walk away” from the relationship. To avoid this, it is customary for the receiver to return a small coin as a symbolic purchase.

Noodles for Birthdays

Long, uncut noodles symbolize longevity and smooth life paths. On birthdays, Koreans often eat janchi guksu (banquet noodles), similar to “longevity noodles” in China.

Seaweed Soup Before Exams

While seaweed soup (miyeokguk) is eaten on birthdays for health, it is avoided before exams. Its slipperiness symbolizes knowledge slipping away.

Meal Offerings for Spirits

A portion of each dish may be removed and discarded outside as an offering to wandering spirits or guardian deities. This small sacrifice ensures spirits are appeased and do not cause harm (Kendall, 2009).

No Garbage After Sunset

Throwing trash away at night risks attracting negative spirits, as dusk belongs to the yin realm, associated with ghosts and misfortune.

Matchsticks on the Roof

Tossing burnt matchsticks onto the roof is believed to protect the household, using the symbolic power of fire to ward off evil.

Birds on Greeting Cards

Birds symbolize flight and departure. Placing bird imagery on cards, especially for celebrations, is avoided, as it could suggest the recipient “flying away.”

Conclusion: Superstitions as Cultural Wisdom

While many Koreans today may not follow these superstitions strictly, they remain woven into cultural consciousness. From avoiding red ink to serving long noodles, these practices reveal how Koreans have historically balanced the worlds of the living and the spiritual. Even as Korea modernizes, superstitions serve as a reminder that life is guided not only by logic, but by respect for unseen forces and ancestral wisdom.

References:

Fortune Cat on X: “Check out this infographic about KOREAN SUPERSTITIONS! #korean #goodluck #fortunecat #superstitions http://t.co/Up2HDEXNvI” / X. (n.d.). X (Formerly Twitter). https://x.com/FortuneCatAu/status/438563313266335744

Kendall, L. (2009). Shamans, housewives, and other restless spirits: Women in Korean ritual life. University of Hawaii Press. https://archive.org/details/shamanshousewive0000kend

Reuters. (2007, July 9). Electric fans and South Koreans: a deadly mix? Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/electric-fans-and-south-koreans-a-deadly-mix-idUSSEO210261/?utm_source=chatgpt.com