Understanding Practice, Physiology, and Misconceptions

In today’s wellness landscape, cupping therapy has re-emerged as a widely used modality for relieving pain, improving circulation, and supporting holistic healing. Despite its growing popularity, many people unfamiliar with Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) often confuse the distinct circular marks left by cupping with bruises from injury. Though they appear similar, the mechanisms, meanings, and physiological effects are fundamentally different. This article provides a thorough understanding of cupping therapy, its roots in TCM, its interpretation through the lens of Western science, and how it compares to traumatic bruising, to clarify misconceptions and deepen appreciation for this ancient practice.

What Is Cupping Therapy?

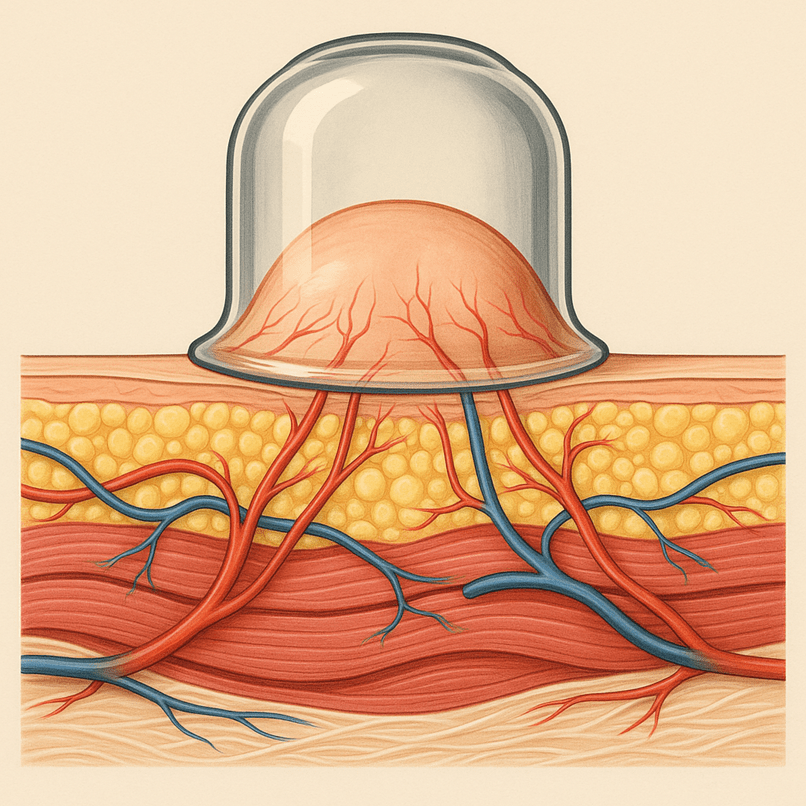

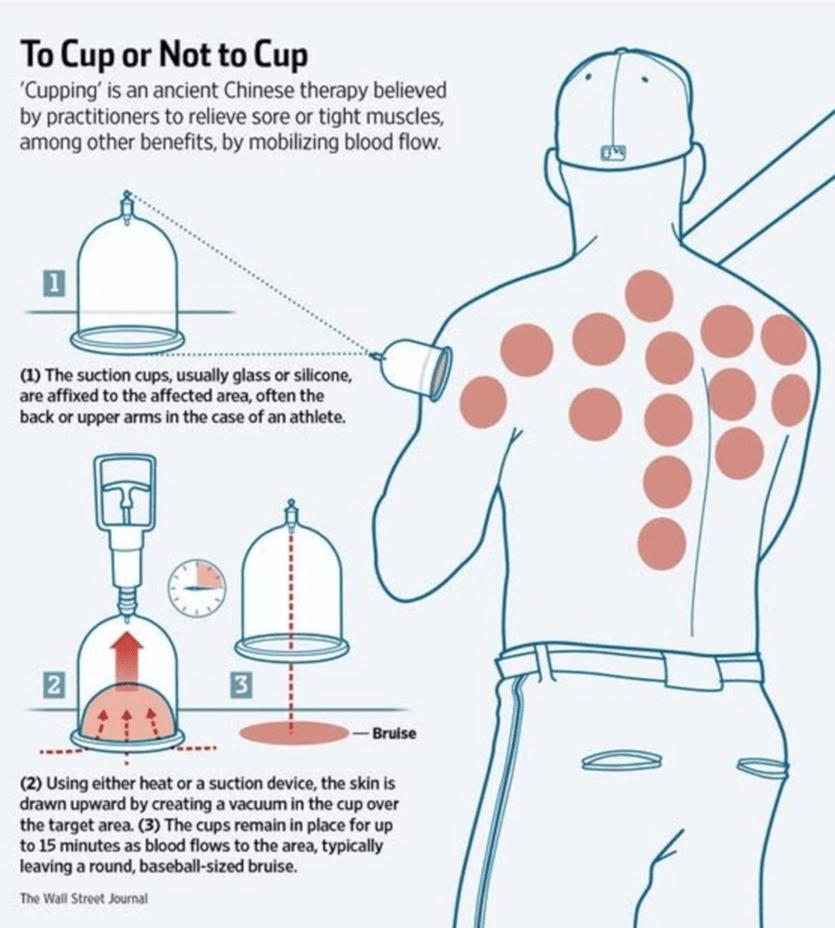

Cupping is a technique that involves placing specially designed cups (glass, silicone, bamboo, or plastic) onto the skin to create suction. The suction pulls the skin and superficial tissue upward, promoting blood flow, stimulating lymphatic drainage, and mobilizing stagnation.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), cupping is used to:

– Move stagnant qi and blood

– Expel pathogenic factors (wind, cold, damp)

– Open the meridians and facilitate energy flow

– Relieve pain, tightness, and toxicity

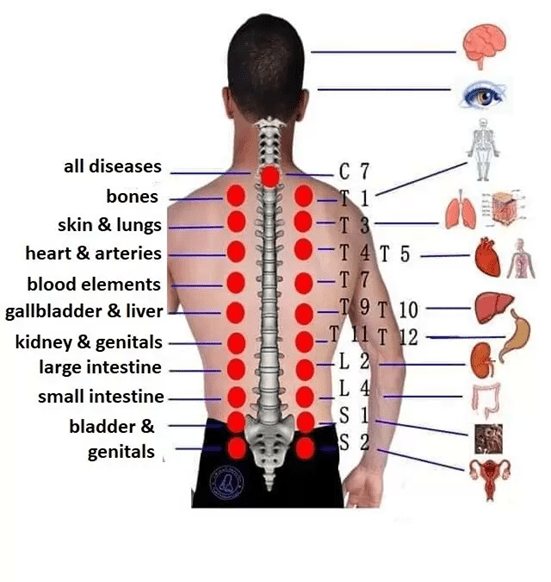

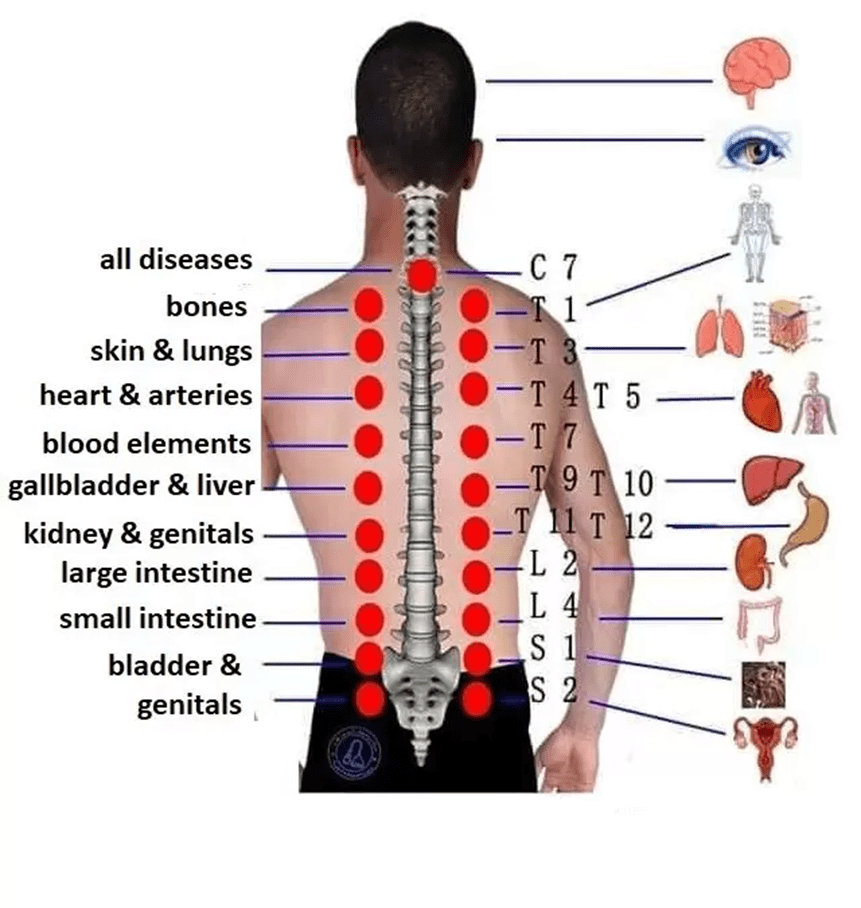

– Strengthen organ function by targeting specific meridian points

The Western Physiological View: How Cupping Works

Western medicine traditionally lacked a framework for cupping, but increasing interest has revealed several plausible mechanisms:

- Increased Local Blood Flow – Suction draws blood to the surface, improving microcirculation (Lowe, 2017).

2. Fascial Decompression – Cupping lifts and separates skin, fascia, and underlying muscles, similar to myofascial release.

3. Neurovascular and Pain Modulation – Stimulation triggers responses through the Gate Control Theory of Pain (Teut et al., 2018).

4. Controlled Inflammatory Response – Mild trauma initiates a low-grade inflammatory response (Furhad et al., 2023)

5. Lymphatic Drainage – The pressure differential helps clear toxins and reduce swelling.

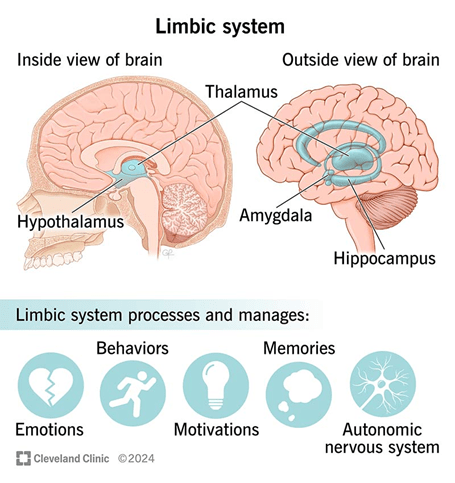

6. Parasympathetic Nervous System Activation – Can reduce stress and activate rest-and-digest mode (Harvard Health Publishing, 2016).

Types of Cupping

– Dry Cupping: Standard suction without bloodletting

– Wet Cupping (Hijama): Involves superficial pricking after suction

– Fire Cupping: Traditional method using heat to create vacuum inside the cup

– Gliding (Massage) Cupping: Cups are moved across oiled skin for deep tissue stimulation

Understanding Bruising from Injury

A bruise (contusion) results from accidental trauma to soft tissue, leading to rupture of capillaries and pooling of blood under the skin. This causes pain, swelling, discoloration, and inflammation. Unlike the controlled effect of cupping, bruising often involves deeper tissue damage.

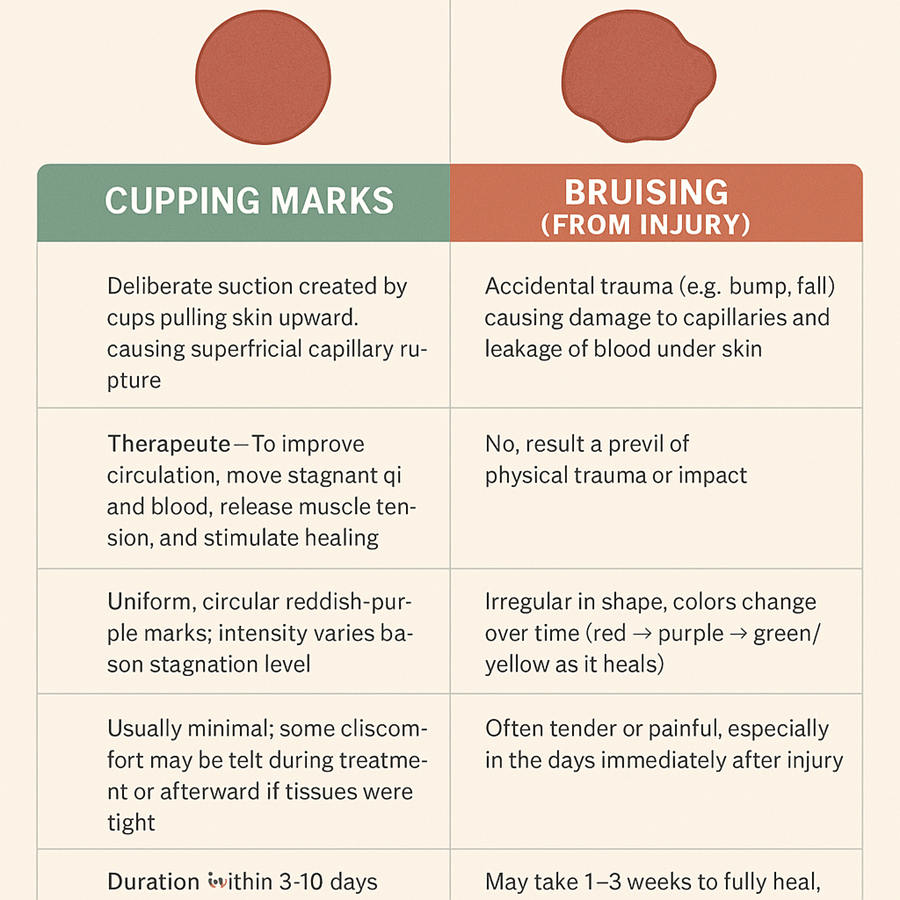

Comparison: Cupping Marks vs. Bruises

Cupping Marks vs. Bruises:

– Cause: Suction-induced capillary rupture vs. blunt trauma

– Intentional: Yes vs. No

– Purpose: Healing vs. Accidental

– Appearance: Uniform circles vs. irregular, color-changing marks

– Pain: Minimal vs. often painful

– Duration: 3–10 days vs. 1–3 weeks

Final Thoughts: Healing vs. Harm

Cupping is not a bruise in the conventional sense. It’s a controlled, purposeful therapy used to stimulate the body’s self-healing mechanisms. While cupping marks may resemble bruises visually, their nature, origin, and physiological impact are completely different. Understanding these differences demystifies this ancient therapy and makes it more approachable for those seeking holistic healing.

⚖️ Side-by-Side Comparison: Cupping Marks vs. Bruises

| Aspect | Cupping Marks | Bruises (Injury) |

| Cause | Suction-induced capillary rupture | Blunt trauma to tissues |

| Intentional? | Yes – therapeutic | No – accidental |

| Purpose | Detox, release stagnation, promote healing | None – consequence of trauma |

| Appearance | Uniform, circular, reddish-purple | Irregular, color changes over time |

| Pain Level | Minimal to none | Tender or painful, often with swelling |

| Color Pattern | Dark → fade gradually | Red → purple → green → yellow |

| Duration | 3–10 days | 1–3 weeks, depending on severity |

| Associated Symptoms | Relief, improved mobility, relaxation | Inflammation, soreness, potential joint restriction |

References:

Furhad, S., Sina, R. E., & Bokhari, A. A. (2023, October 30). Cupping therapy. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538253/

Harvard Health Publishing. (2016). What exactly is cupping? Harvard Health Blog. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-exactly-is-cupping-2016093010402

Johannes, L. (2012, November 12). Centuries-Old art of cupping may bring some pain relief. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324073504578114970824081566

Lowe, D. T. (2017). Cupping therapy: An analysis of the effects of suction on skin and the possible influence on human health. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 29, 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.09.008

Teut, M., Ullmann, A., Ortiz, M., Rotter, G., Binting, S., Cree, M., Lotz, F., Roll, S., & Brinkhaus, B. (2018). Pulsatile dry cupping in chronic low back pain – a randomized three-armed controlled clinical trial. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-018-2187-8