Understanding the Difference Between the 12 Primary Meridians and the 8 Extraordinary Vessels in Traditional Chinese Medicine

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) views the human body as an intricate network of energy channels that govern physical, emotional, and spiritual health. Two key components of this system are the 12 Primary Meridians and the 8 Extraordinary Vessels. Though they are interconnected, they serve distinctly different roles in maintaining balance and vitality. Understanding this distinction provides deeper insight into how TCM approaches healing, longevity, and self-cultivation (Maciocia, 2005).

The 12 Primary Meridians: The Body’s Main Rivers of Life

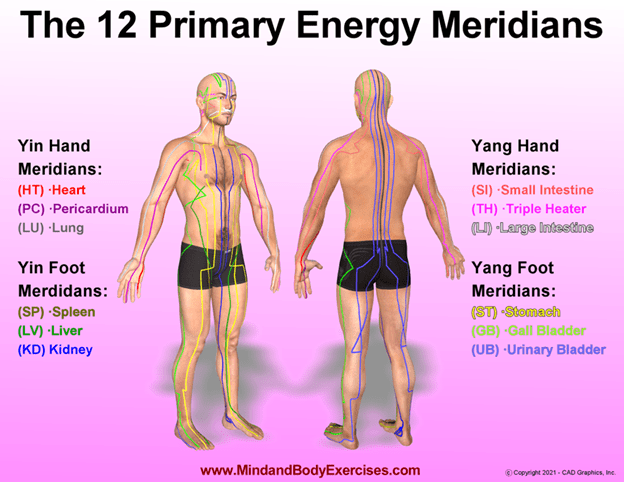

The 12 Primary Meridians are the foundational pathways through which Qi (vital energy) and blood flow to nourish the entire body (Deadman et al., 2007). These channels are intimately linked to the Zang-Fu organs of the five Yin organs (Lung, Heart, Spleen, Liver, Kidney) and six Yang organs (Large Intestine, Small Intestine, Stomach, Gallbladder, Urinary Bladder, and San Jiao/Triple Burner) (Maciocia, 2005).

Each meridian runs a defined, bilateral path along the body, connecting exterior regions (skin, muscles) with interior organs. This ensures that nutritive Qi (Ying Qi) and protective Qi (Wei Qi) are continuously circulated, supporting physiological functions such as immunity, metabolism, digestion, and mental clarity (Kaptchuk, 2000).

Because they regulate the daily functional balance of the body, the Primary Meridians are often the primary focus in acupuncture treatments and other therapeutic practices like acupressure and Tuina massage(Deadman et al., 2007). When these channels are blocked or imbalanced, symptoms such as pain, fatigue, or organ dysfunction can arise.

The 8 Extraordinary Vessels: The Deeper Reservoirs of Vital Energy

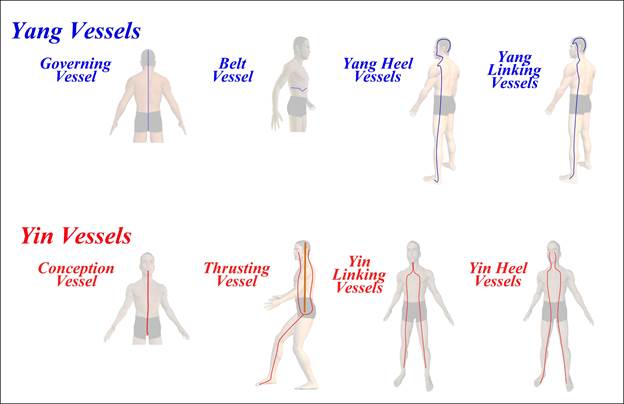

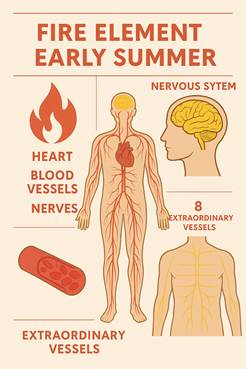

In contrast to the Primary Meridians, the 8 Extraordinary Vessels operate at a deeper energetic level. They are not directly tied to the Zang-Fu organs, nor do they participate in the body’s regular organ-based circulation (Maciocia, 2005). Instead, they act as reservoirs and regulators of Qi and Blood, particularly Yuan Qi (Original or Prenatal Qi), which governs growth, development, and constitutional strength (Hsu, 1999).

While the Primary Meridians are paired and bilateral, several Extraordinary Vessels run along the midline of the body (such as the Du Mai or Governing Vessel and the Ren Mai or Conception Vessel), forming the body’s central energetic axis. Others, such as the Chong Mai (Penetrating Vessel) and Dai Mai (Belt Vessel), regulate more specialized functions like reproductive health and structural integration (Deadman et al., 2007).

The Extraordinary Vessels become especially important during times of:

- Life transitions (puberty, pregnancy, menopause)

- Chronic illness

- Emotional trauma

- Deep constitutional imbalance (Birch & Felt, 1999)

In such cases, they provide a reservoir of Qi and Blood that can be mobilized to restore balance and support healing. Advanced acupuncture treatments often target these vessels to address long-standing patterns of disease or to promote profound transformation (Birch & Felt, 1999).

Comparing the Two Systems: A Summary Table

| Feature | 12 Primary Meridians | 8 Extraordinary Vessels |

| Number | 12 | 8 |

| Connection to Organs | Directly connected to major Zang-Fu organs | Not directly connected to Zang-Fu; deeper level |

| Flow of Qi | Circulates protective and nutritive Qi (Wei & Ying) | Regulates and stores Yuan Qi (Original Qi) |

| Pathway | Relatively superficial, follows defined body paths | Deep, more latent or reservoir-like pathways |

| Main Function | Maintains daily physiological function and organ balance | Acts as reservoirs of Qi and Blood; regulate overflow; integrate all meridians |

| Symmetry | Paired and bilateral (left and right sides) | Some are midline (single), others bilateral |

| Origin and Circulation | Continuous circulation in a closed loop | Originate from the Kidney/Yuan Qi level; flow in special patterns |

| Activation in Practice | Commonly used in acupuncture and daily therapies | Used in advanced, constitutional, or chronic condition treatments |

| Examples | Lung, Heart, Kidney, Spleen, Stomach meridians, etc. | Du Mai, Ren Mai, Chong Mai, Dai Mai, and others |

The Dynamic Dance of Qi: Rivers and Reservoirs

One way to visualize this relationship is to think of the 12 Primary Meridians as the body’s main rivers of energy flow (Kaptchuk, 2000). They nourish the landscape (organs and tissues) with a steady stream of Qi and Blood. In contrast, the 8 Extraordinary Vessels serve as reservoirs and aqueducts that hold, regulate, and distribute this energy as needed during times of surplus or deficiency (Hsu, 1999).

This layered system allows TCM to address health at multiple levels, from acute, surface-level imbalances to deep constitutional healing that shapes one’s vitality, longevity, and adaptability (Birch & Felt, 1999).

Practical Implications for Wellness

For modern practitioners and wellness seekers, understanding this distinction helps guide personal practices:

- Daily self-care and lifestyle habits (nutrition, breathwork, basic movement practices) primarily support the flow of the 12 Primary Meridians.

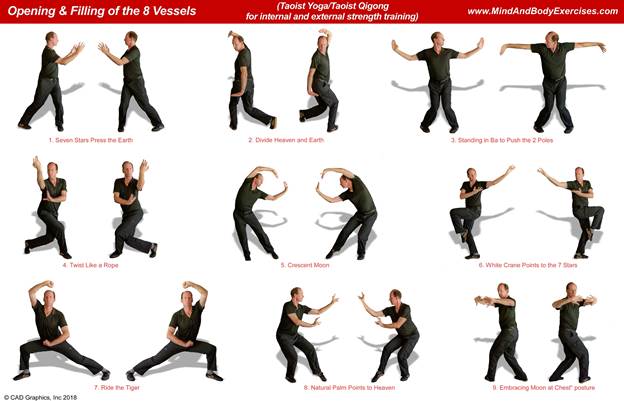

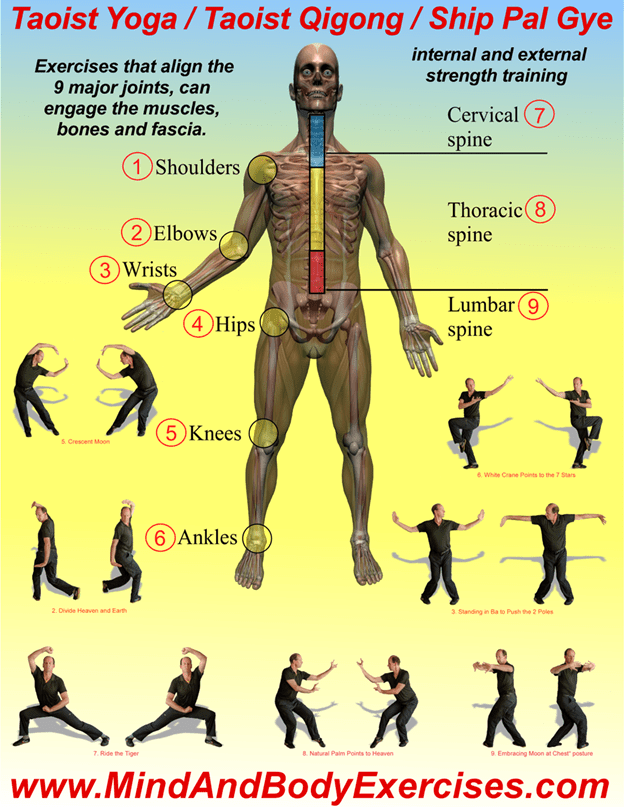

- Deeper practices such as Qi Gong, Nei Gong, and meditative breathwork can engage the Extraordinary Vessels to cultivate life force and restore balance at a core level (Deadman et al., 2007).

- Clinical interventions (like specialized acupuncture protocols) can be designed to activate specific Extraordinary Vessels to address chronic or deeply rooted issues (Birch & Felt, 1999).

Conclusion

Both the 12 Primary Meridians and the 8 Extraordinary Vessels are essential components of the TCM energy system, working together to maintain health, resilience, and harmony throughout life (Maciocia, 2005). By appreciating their complementary roles, we gain a richer understanding of how traditional practices can support modern well-being in a profound and holistic way.

References:

Birch, S., & Felt, R. L. (1999). Understanding acupuncture. Churchill Livingstone.

Deadman, P., Al-Khafaji, M., & Baker, K. (2007). A manual of acupuncture. Journal of Chinese Medicine Publications.

Hsu, E. (1999). The transmission of Chinese medicine. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511612459

Kaptchuk, T. J. (2000). The web that has no weaver: Understanding Chinese medicine (2nd ed.). Contemporary Books.

Maciocia, G. (2005). The foundations of Chinese medicine: A comprehensive text for acupuncturists and herbalists (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone.