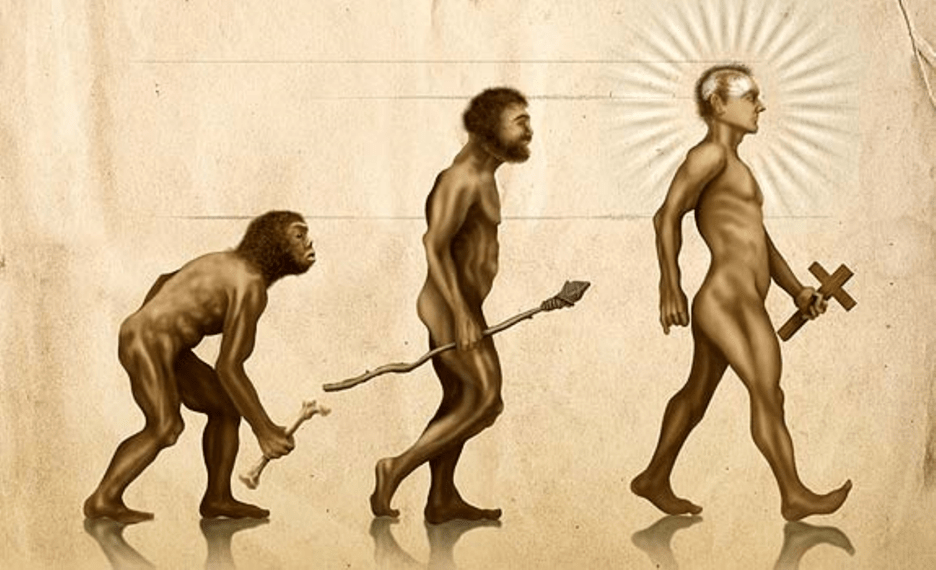

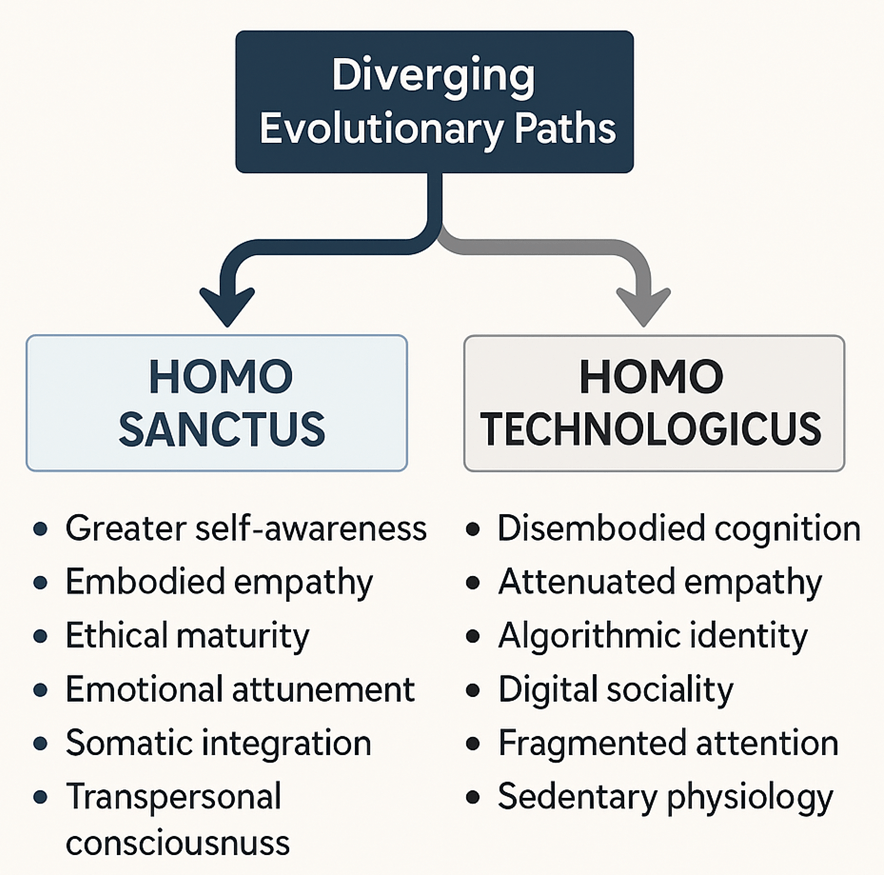

Human evolution has traditionally been described through biological shifts, evolving from Homo habilis, Homo erectus, and Homo sapiens. Yet in the 21st century, the forces shaping human development are increasingly cultural, technological, and behavioral, not solely genetic. Two contrasting models have emerged in scholarly, philosophical, and sociocultural discourse: the spiritually and ethically “evolved” Homo Sanctus, and the digitally dependent, socially attenuated Homo Technologicus.

These models represent divergent paths of human adaptation to radically new environments. One emphasizes deeper consciousness, embodied awareness, and integrated development; the other reflects disembodied cognition, algorithmic identity, and diminishing interpersonal fluency. When viewed through the lenses of psychology, epigenetics, neuroscience, and social evolution, these models are not merely metaphors, but they reflect distinct adaptive pressures shaping tomorrow’s humans.

This essay synthesizes both trajectories, integrates current scientific literature, and positions them within a holistic, mind–body–spirit framework aligned with martial arts, qigong, and embodied wisdom traditions.

1. Homo Sanctus: The Archetype of the Integrated Human

The term Homo Sanctus appears in spiritual psychology, evolutionary theology, and transpersonal philosophy to describe a “next-stage human” characterized by higher ethical consciousness, embodied awareness, and profound relational intelligence (Mukhopadhyay, 2021). Rather than a biological species, Homo Sanctus is a developmental ideal, where a human who transcends ego-fragmentation and embodies unity between body, mind, society, and spirit.

Core characteristics of Homo Sanctus include:

- Embodied presence: deep interoception, somatic awareness, and emotional regulation

- Ethical maturity: compassion, integrity, service

- Integration of opposites: harmonizing rationality and intuition, self and other

- Transpersonal consciousness: connectedness to something larger than the self

- Cohesive identity: clarity of values, meaning, and purpose

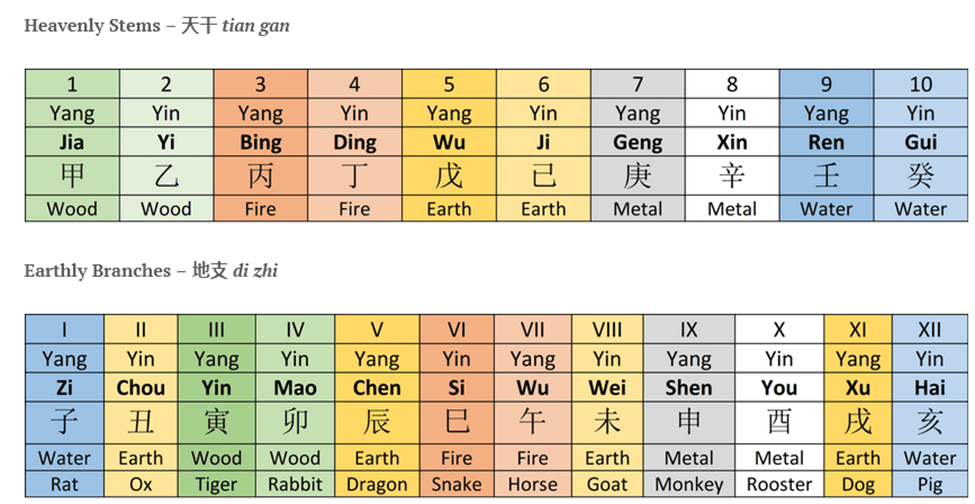

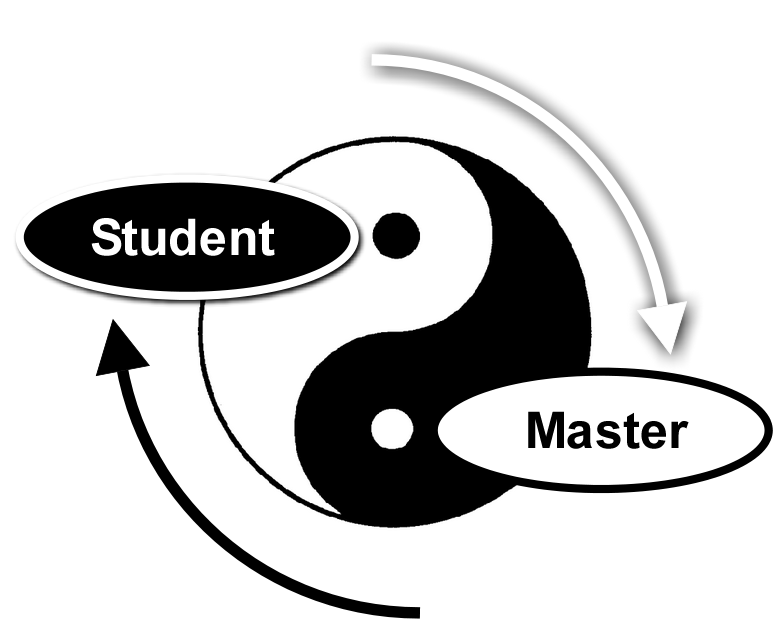

This ideal parallels traditions such as the Taoist zhenren (“true person”), Confucian junzi (“noble person”), the Buddhist bodhisattva, and Christian spiritual maturity (Wilber, 2000). From an Eastern-martial perspective, this represents the Warrior–Scholar–Sage archetype: strong in body, disciplined in mind, and aligned in spirit.

Importantly, Homo Sanctus evolves through cultivation, not accident. Practices such as tai chi, qigong, meditation, dao yin, and martial mastery refine the nervous system, harmonize the meridian networks, and deepen interoception (Wayne & Kaptchuk, 2008). Such individuals become more resilient, socially attuned, and less susceptible to technological fragmentation.

2. The Counter-Trajectory: Homo Technologicus and the Decline of Interpersonal Competence

In contrast, emerging research indicates that modern humans, especially younger generations, are undergoing a decline in face-to-face relational skills, empathy, and social nuance. This pattern reflects a different adaptive pathway: Homo Technologicus, a human shaped primarily by digital environments.

Key drivers include:

- heavy reliance on text-based communication

- diminished exposure to real-time social cues

- algorithmic reinforcement loops

- parasocial relationships and AI companions

- chronic sedentary behavior

- online identity construction

- declining sexual activity and pair bonding

This developmental pattern is supported by evidence showing measurable declines in empathy over the past 30 years (Konrath et al., 2011), reductions in attention span associated with digital multitasking (Loh & Kanai, 2016), and decreased interpersonal resilience due to avoidance of embodied conflict (Kross et al., 2013).

2.1 Loss of Social Neurobiological Skills

Human communication is 70–93% nonverbal (Burgoon et al., 2016). Digital communication removes:

- microexpressions

- tone, cadence, prosody

- posture and gesture

- physiological co-regulation

The brain circuits responsible for reading these cues, including the mirror neuron system, the insula, and the temporoparietal junction, atrophy with disuse (Iacoboni, 2009). Adolescents who use screens more than three hours daily show impairments in social brain network integration (Twenge & Campbell, 2018). This is evolutionary pressure in real time.

2.2 Declining Sexual Drive and Reproductive Behavior

Sexual activity among young adults has plummeted, with many reporting no sexual activity for months or years, often replaced by digital substitutes (Ueda et al., 2020). Chronic screen exposure, pornography addiction, disrupted circadian rhythms, and social anxiety all reduce libido and mating motivation via hormonal pathways, especially dopamine and testosterone regulation (Prause & Pfaus, 2015).

From an evolutionary lens, those who do not reproduce are naturally selected out. This creates behavioral selection pressure for traits that preserve reproductive drive and embodied bonding.

3. Sedentary Lifestyle, Biological Decline, and Epigenetic Consequences

Sedentary lifestyles, disrupted sleep patterns, virtual emotional engagement, and constant digital stimulation contribute to:

- metabolic dysfunction

- chronic low-grade inflammation

- decreased fertility

- hormonal disruption

- accelerated aging

Sedentary behavior reduces mitochondrial efficiency and alters hormonal pathways related to stress, libido, and mood (Booth et al., 2012). Chronic stress, sleep disruption, and social deprivation produce epigenetic changes that can pass to offspring (Nestler, 2014).

Examples include:

- altered DNA methylation affecting stress response genes

- sperm epigenetic damage from obesity and inactivity

- maternal circadian disruption impairing offspring metabolic regulation

Thus, today’s lifestyle patterns may literally reshape the biological baseline of future generations, even without genetic mutation.

4. Diverging Evolutionary Forks: Homo Integralis vs. Homo Fragmentus

Taken together, contemporary conditions create a bifurcated evolutionary trajectory:

Path A: Homo Technologicus / Homo Fragmentus

Characterized by:

- reduced interpersonal intelligence

- emotional outsourcing to AI

- fragmented identity

- dopamine dysregulation

- decreased libido and reproduction

- digital tribalism

- low distress tolerance

- sedentary physiology

- weakened mind–body integration

Over generations, this pathway selects for:

- reduced mating drive

- increased digital dependency

- lower embodied cognition

This is not dystopian fiction, this is ongoing.

Path B: Homo Sanctus / Homo Integralis

Characterized by:

- strong somatic awareness

- embodied empathy

- resilience to stress

- integrated spiritual-ethical development

- intentional cultivation (qigong, tai chi, martial arts)

- disciplined nervous system

- strong social bonds

- meaningful service

- stable identity

This pathway reflects the continuation of human strengths that enabled our survival for 300,000 years, community, embodiment, adaptability, and consciousness.

5. A Holistic Perspective: Embodiment as the Antidote

My life’s work of martial arts, qigong, Taoist philosophy, and holistic health, directly counters the fragmentation of Homo Technologicus.

Embodied practices strengthen:

- vagal tone

- emotional regulation

- stress resilience

- interoception

- empathy

- ethical clarity

- community cohesion

- nervous system balance

Tai Chi, for example, enhances functional connectivity in brain regions related to attention, emotion, and social cognition (Tao et al., 2016). Meditation thickens areas of the brain involved in compassion and self-regulation (Lazar et al., 2005). Qigong improves heart rate variability, endocrine balance, and neuroimmune communication (Jahnke et al., 2010).

In this context, the true “next stage” of human evolution may not be technological augmentation but re-embodiment, integration, and cultivation, aligning with the ancient ideal of Homo Sanctus.

Conclusion

Humanity stands at a developmental crossroads. One path leads toward disembodied cognition, digital dependence, diminished interpersonal capacities, and biological decline, with perhaps the emergence of Homo Technologicus and Homo Fragmentus. The other leads toward embodied presence, ethical wholeness, social coherence, and heightened consciousness, or the pathway of Homo Sanctus and Homo Integralis.

This evolutionary divergence is not predetermined. It is shaped by choices, practices, environments, and values. Through holistic training, martial arts, breathwork, qigong, and the cultivation of meaning, humans can choose to evolve toward greater integration rather than fragmentation.

My work of writings, and teachings sit firmly within this integrative lineage. In a world moving toward digital disembodiment, the embodied path has never been more necessary or more evolutionary.

Comparison Table: Emerging Human Trajectories

| Dimension | Homo Sanctus | Homo Integralis (holistic path) | Homo Technologicus | Homo Fragmentus |

| Core Identity | Spiritually evolved, ethically matured human | Fully embodied, integrated mind–body–spirit development | Human identity shaped by technology, algorithms, digital environments | Fragmented sense of self shaped by dopamine loops, isolation, and virtual life |

| Consciousness | Transpersonal, expansive, meaning-driven | High interoception, self-awareness, balanced cognition | Externally directed, attention hijacked by devices | Scattered, reactive, overstimulated consciousness |

| Social Intelligence | Deep empathy, compassion, relational wisdom | Strong interpersonal presence, face-to-face fluency | Digital sociality replacing real interaction | Loss of nuance, reduced empathy, decreased communication skills |

| Emotion Regulation | Stable, grounded, ethically aligned | Practices that strengthen vagal tone, breath, resilience | Outsourced to technology (apps, AI) | Dysregulated, impulsive, avoidance-based |

| Embodiment | Harmonized body–mind–spirit; somatic integration | Tai chi, qigong, breathwork, martial arts cultivate coherence | Sedentary lifestyle, physical disengagement | Physically weakened; poor posture, low vitality |

| Motivational Drive | Purpose, service, meaning | Discipline, intentional cultivation, self-development | Dopamine-driven novelty-seeking | Anhedonia, apathy, low libido |

| Reproductive Behavior | Strong bonding, stable relationships | Healthy sexual energy and emotional intimacy | Declining libido; digital substitutes | Sexual avoidance, collapse of long-term pair bonding |

| Health Trajectory | Balanced hormones, strong immunity | High resilience, longevity potential | Metabolic dysfunction, circadian disruption | Chronic stress, inflammatory burden, poor biological function |

| Connection to Reality | Embodied presence, clear perception | Integration of physical, mental, and higher awareness | Simulation-based worldview | Detachment from reality, dissociation, escapism |

| Developmental Pathway | Self-cultivation → ethical maturation → consciousness expansion | Somatic calibration → iterative self-cultivation → transmutation | Convenience → dependence → cognitive offloading | Interruption → fragmentation → decline |

| Long-Term Evolutionary Outcome | Homo Sanctus (ideal human maturity) | Homo Integralis (embodied evolutionary lineage) | Homo Technologicus (digitally adapted) | Homo Fragmentus (socially diminished) |

References:

Booth, F. W., Roberts, C. K., & Laye, M. J. (2012). Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Comprehensive Physiology, 2(2), 1143–1211. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c110025

Burgoon, J.K., Guerrero, L.K., & Manusov, V. (2021). Nonverbal Communication (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003095552

Iacoboni, M. (2009). Mirroring people: The new science of how we connect with others. Picador.

Jahnke, R., Larkey, L., Rogers, C., Etnier, J., & Lin, F. (2010). A comprehensive review of health benefits of qigong and tai chi. American journal of health promotion : AJHP, 24(6), e1–e25. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.081013-LIT-248

Konrath, S., O’Brien, E., & Hsing, C. (2011). Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(2), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377395

Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., et al. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e69841. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069841

Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., et al. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. NeuroReport, 16(17), 1893–1897. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19

Loh, K. K., & Kanai, R. (2016). How has the Internet reshaped human cognition? The Neuroscientist, 22(5), 506–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858415595005

Mukhopadhyay, A. K. (2021). Science of information. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350948703_Science_of_Information

Nestler E. J. (2014). Epigenetic mechanisms of depression. JAMA psychiatry, 71(4), 454–456. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4291

Prause, N., & Pfaus, J. (2015). Viewing Sexual Stimuli Associated with Greater Sexual Responsiveness, Not Erectile Dysfunction. Sexual medicine, 3(2), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/sm2.58

Redazione, & Redazione. (2025, January 17). Homo technologicus, homo spiritualis. Trascendente Digitale. https://www.trascendentedigitale.it/primaria/metafisica/homo-technologicus-homo-spiritualis/

Tao, J., Liu, J., Egorova, N., Chen, X., Sun, S., Xue, X., Huang, J., Zheng, G., Wang, Q., Chen, L., & Kong, J. (2016). Increased Hippocampus-Medial Prefrontal Cortex Resting-State Functional Connectivity and Memory Function after Tai Chi Chuan Practice in Elder Adults. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 8, 25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2016.00025

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003

Ueda, P., Mercer, C. H., Ghaznavi, C., & Herbenick, D. (2020). Trends in frequency of sexual activity and number of sexual partners among adults aged 18 to 44 years in the US, 2000-2018. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e203833. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3833

Wayne, P. M., & Kaptchuk, T. J. (2008). Challenges inherent to t’ai chi research: part I–t’ai chi as a complex multicomponent intervention. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.), 14(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2007.7170a

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Shambhala.