Origins and Lore

The concept of Dim Mak often translated “pressing the pulse/vessel”) occupies a curious place in martial lore. Sometimes referred to as the “delayed death touch,” it is imagined as a set of techniques targeting subtle points on the body to cause paralysis, unconsciousness, or even death, sometimes instantly, sometimes hours or days later. In Cantonese opera, wuxia fiction, and 20th-century martial arts marketing, this idea became a central trope. Related Japanese traditions, such as kyūsho-jutsu, also emphasize striking “vital points” (Kim & Bookey, 2008).

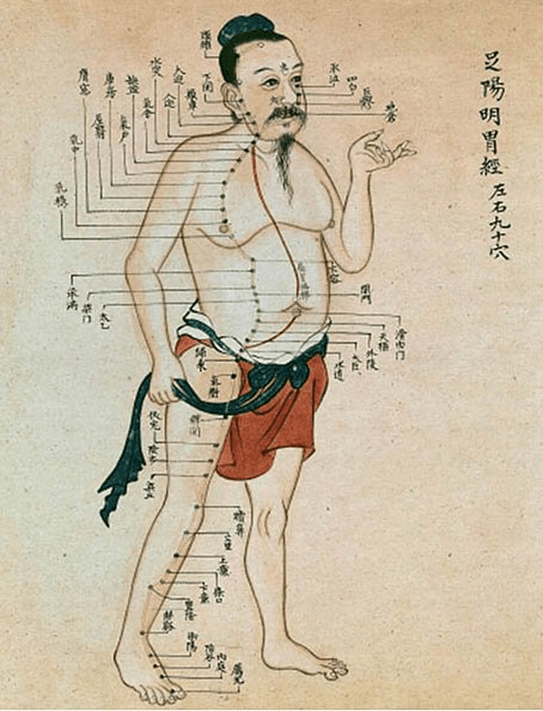

One historical root is the Bubishi, a Southern Chinese martial and medical manual carried to Okinawa and preserved in karate circles. It contains anatomical diagrams and pressure-point charts, blending medicine and combat knowledge. However, nothing in the Bubishi describes a reproducible “death touch on a timer.” The delayed-death legend is largely a product of mythologizing (McCarthy, 1995).

Physiological Realities

Although the notion of a mystical “death touch” has no scientific foundation, certain strikes can produce catastrophic effects. For example:

- Commotio cordis: A sudden blow to the chest directly over the heart during a critical phase of the cardiac cycle can trigger lethal arrhythmias, especially in young athletes. Death is rapid, not delayed (Maron et al., 2010).

- Carotid sinus reflex: Pressure or trauma at the neck can overstimulate baroreceptors, causing sudden fainting or, in rare cases, cardiac arrest (Sutton, 2014).

- Internal injuries: Abdominal trauma may produce a delayed splenic rupture, with fatal bleeding occurring days after impact (Coccolini et al., 2017). Likewise, epidural hematomas following head trauma can present with a “lucid interval” before deterioration (Ganz, 2013). These medical realities may explain reports of “delayed death” after apparently minor strikes.

In short, so-called Dim Mak events correspond more closely to rare but recognized trauma complications, not an esoteric martial formula.

“Injury Without Touch” and Nei Gong

Claims that a Nei Gong (or neidan) master can injure or incapacitate another person without physical contact remain anecdotal and unverified. Controlled tests and skeptical investigations have repeatedly failed to reproduce reliable no-touch effects; where dramatic results are reported, more plausible explanations include expectancy and conditioned responses among students, theatrical staging or confederates, suggestion/hypnosis, and the nocebo/placebo effect. Importantly, some real medical conditions (for example, cardiac arrhythmia after blunt chest trauma or delayed intracranial bleeding) can cause delayed collapse and have sometimes been misattributed to mysterious causes — but these are documented trauma or medical events, not proof of transmissible ‘external qi.’ Because of the unpredictability of medical reactions, any attempt to provoke physiological responses in others without informed consent raises serious ethical and legal issues; responsible teachers therefore emphasize biomechanics, safety, and transparent demonstration methods rather than secret lethal techniques.

Some modern teachers link Dim Mak to nei gong (“internal work”) breath, alignment, and energetic exercises said to cultivate the ability to project qi or chi (vital force) externally. Demonstrations of “no-touch knockouts” or “chi projection” circulate widely, often framed as injury without contact.

Under controlled testing, however, such claims collapse. Televised investigations and academic studies show that subjects who are not suggestible or part of the teacher’s own group remain unaffected by “no-touch” attempts (Shermer, 1997). The most plausible explanation is psychological, where expectancy, compliance, or hypnotic influence are the cause, not physics or bioenergetics. Practitioners cannot safely test these methods without risking harm. Ethical training instead focuses on biomechanics, leverage, and simulation rather than attempts at real no-touch injury.

Why “injure without touch” raises serious moral problems

- Unpredictable risk. Because some medical events (arrhythmia, stroke, internal bleeding) can be triggered unpredictably by stress or minor provocation, any attempt to produce physiological effects remotely risks serious harm. You cannot ethically justify causing that risk.

- Consent & autonomy. Attempting to alter someone’s physiology or mental state without explicit, informed consent violates basic bodily and mental autonomy.

- Deception and coercion. Teaching secret “no-touch” attack methods encourages deception, exploitation, and misuse, especially in hierarchical groups. That fosters abusive dynamics.

- Legal exposure. Even “demonstrations” that cause collapse, panic, or later medical problems can produce criminal liability and civil suits. Teachers are responsible for foreseeable harm.

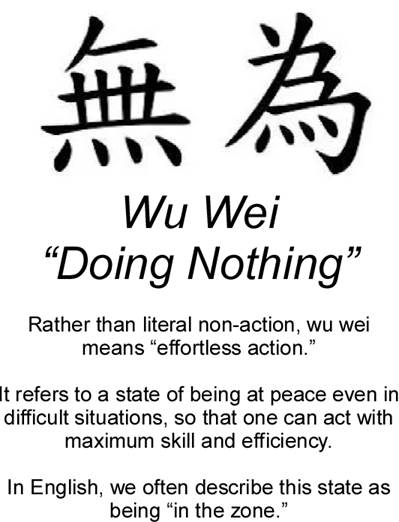

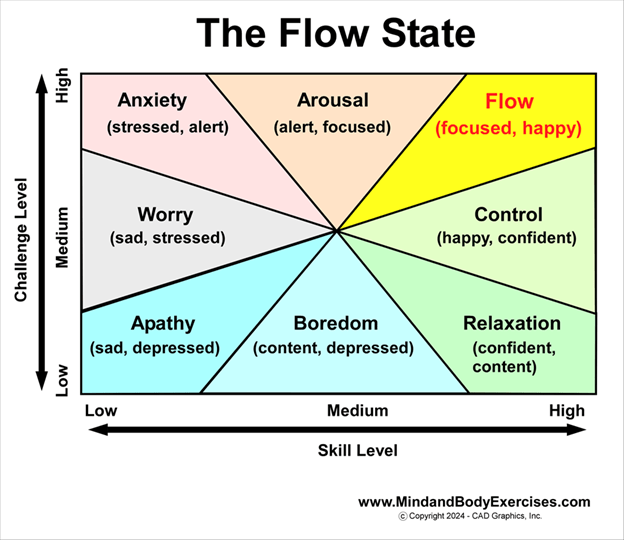

That said, nei gong is highly valuable when understood in biomechanical terms. Internal training improves body structure, breath regulation, and fa jin (explosive force issuance). This allows practitioners to deliver maximum impact with minimal motion and appear almost effortless. The “mystical” layer is metaphorical; the real effect is better mechanics (Frantzis, 2007).

Ethics and Modern Practice

Because of the risks of striking vulnerable areas, serious martial arts traditions emphasize responsibility. Knowing that a blow to the chest or neck could cause unforeseen medical emergencies, modern teachers stress restraint, safety protocols, and familiarity with first aid and CPR.

From a holistic view, Dim Mak reminds us that mythology often grows around kernels of truth. Striking the body does carry risk, but not in the cinematic, time-delayed fashion popularized in movies. Internal practices like nei gong do confer extraordinary skill, but by enhancing efficiency and coordination, not by transmitting lethal force through the air.

References:

Ganz, J. C. (2013). The lucid interval associated with epidural bleeding: Evolving understanding. Journal of Neurosurgery, 118(4), 739–745. https://doi.org/10.3171/2012.12.JNS121264

Coccolini, F., Montori, G., Catena, F., Kluger, Y., Biffl, W., Moore, E. E., Reva, V., Bing, C., Bala, M., Fugazzola, P., Bahouth, H., Marzi, I., Velmahos, G., Ivatury, R., Soreide, K., Horer, T., Broek, R. T., Pereira, B. M., Fraga, G. P., . . . Ansaloni, L. (2017). Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-017-0151-4

Frantzis, B. K. (2007). Opening the energy gates of your body: Qigong for lifelong health. Blue Snake Books. https://archive.org/details/openingenergygat00fran

Kim, S. H. & Bookey. (2008). Vital point strikes. https://cdn.bookey.app/files/pdf/book/en/vital-point-strikes.pdf

Maron, B. J., Estes, N. A. M., Link, M. S., & Wang, P. J. (2010). Commotio cordis. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(10), 917–927. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0910111

McCarthy, P. (1995). The Bubishi: The Bible of karate. Tuttle Publishing. https://ia801201.us.archive.org/32/items/do-it-yourself-and-survival-pdfs/The%20Bible%20of%20Karate_%20Bubishi%20%28%20PDFDrive%20%29_text.pdf

Shermer, M. (1997). Why people believe weird things: Pseudoscience, superstition, and other confusions of our time (rev. ed.). Holt Paperbacks. https://archive.org/details/whypeoplebelieve0000sher

Sutton, R. (2014). Carotid sinus syndrome: Progress in understanding and management. Global Cardiology Science & Practice, 2014(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.5339/gcsp.2014.18