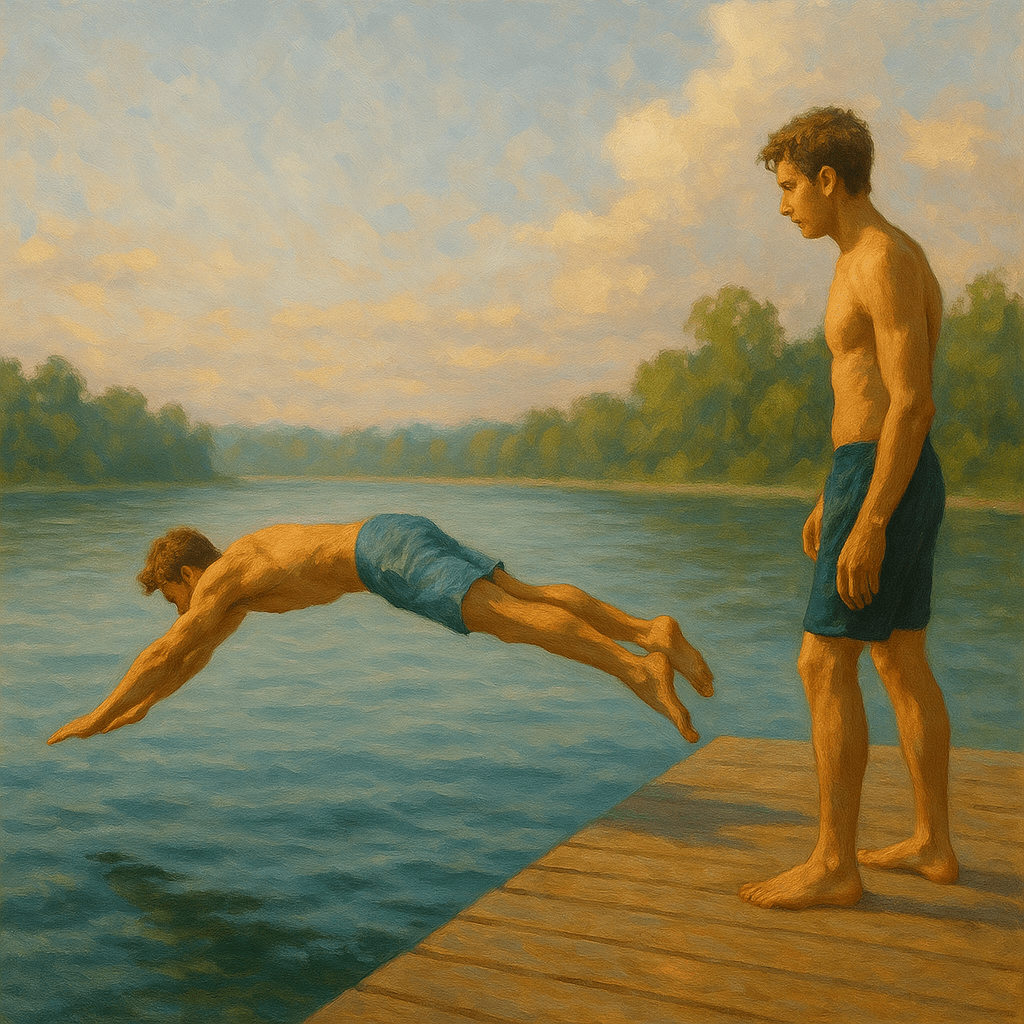

The Power of Full Commitment and Deliberate Presence

Human potential is rarely limited by talent or intelligence; more often, it is diminished by half-hearted effort and a lack of deliberate engagement with the present moment. In every aspect of life, from work and relationships to self-cultivation and spiritual growth, the quality of our actions is determined by the depth of our commitment. Choosing to invest ourselves wholly in what we do, rather than adopting a “renter’s attitude” or performing tasks “half-heartedly,” is one of the most profound determinants of meaning, achievement, and personal integrity. To live fully is to act with intention, awareness, and total presence, to put 100% of oneself into a chosen path or consciously refrain from it altogether.

Half-Effort and the Illusion of Action

Modern society often rewards activity over substance. People multitask, chase productivity, and take pride in “being busy,” yet much of that activity is shallow and unfocused. This is what might be called the “half-effort mentality” where one does just enough to get by, but not enough to grow. Like a renter who avoids investing in a property because they do not truly own it, individuals with a renter’s mindset approach life without deep commitment, leaving their full potential unrealized. This approach is not harmless; it is corrosive. It breeds mediocrity, erodes self-respect, and dulls one’s inner drive for excellence.

The philosopher Aristotle wrote that virtue is a habit cultivated through intentional action (Aristotle, trans. 2014). Excellence, therefore, is not an act but a consistent practice. Every time we choose to give less than our best, we reinforce a pattern of mediocrity. Conversely, when we decide to give our full energy and focus to a task, we cultivate habits of discipline, character, and integrity. In psychological terms, this mirrors the concept of “flow,” a state described by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi (1990) as one in which total immersion in a meaningful activity leads to heightened creativity, satisfaction, and performance. Flow cannot occur in a state of partial attention. It demands complete commitment.

Consequences: The Natural Law of Choice

Human life is structured by choices, and choices inevitably lead to consequences. When we give only partial effort, the consequences reflect that choice: diminished outcomes, missed opportunities, and an ongoing sense of unfulfilled potential. Psychologist Albert Bandura (1997) emphasized the role of self-efficacy, the belief in one’s capacity to act effectively, as a cornerstone of human motivation. Self-efficacy is built through repeated acts of intentional effort. When effort is inconsistent, self-efficacy weakens, and we begin to doubt our own capabilities.

This principle aligns with Eastern philosophical traditions as well. In the Taoist classic Tao Te Ching, Laozi advises, “Do your work, then step back. The only path to serenity” (Laozi, trans. 2009). This teaching implies that one must give themselves wholly to the work, not clinging to the outcome, but ensure the process itself is authentic and complete. The Buddhist concept of right effort (samyak vyayama) similarly teaches that effort is a moral and spiritual imperative: it is through disciplined, wholehearted engagement that we align our actions with our deeper purpose (Rahula, 1974).

Attention, Awareness, and Intent: The Mind as a Tool

Commitment is not merely physical effort. It is also mental presence. To put one’s “mind into” a task is to bring attention, awareness, and intention fully to the present moment. In a culture saturated with distraction, this skill is increasingly rare. Yet neuroscience confirms that focused attention changes the brain: it strengthens neural pathways, enhances memory, and improves cognitive control (Cásedas, 2021). In other words, presence is a form of power.

Deliberate awareness also deepens the meaning of our actions. When we are fully present, whether cooking a meal, engaging in conversation, or practicing a martial art, we transform the mundane into the sacred. Zen teachings often emphasize the phrase ichigyo zammai, meaning “concentration on one action.” This state of single-mindedness turns each moment into a vehicle for awakening and self-transformation. Similarly, Confucius taught that the cultivation of yi (righteous intention) requires conscious attention to one’s conduct in even the smallest acts (Confucius, trans. 1997). The lesson is timeless: how we do anything is how we do everything.

Integrity and the Binary of Commitment

There is a profound simplicity in adopting a binary approach to action: either commit fully or do not commit at all. This approach eliminates the murky middle ground where excuses thrive. It demands clarity of intention before taking action, which in turn strengthens integrity, the alignment of one’s words, values, and behaviors. When we act with half-effort, we often rationalize our lack of results. When we commit fully, we accept responsibility for the outcome, whatever it may be.

Moreover, wholehearted action builds trust, both in ourselves and in others. People who consistently give their best become reliable, respected, and influential. They embody authenticity, a quality philosopher Charles Taylor (1991) argues is essential for a meaningful life in the modern world. Authentic living arises when one’s external actions faithfully express internal values and such alignment is only possible through deliberate, full-hearted engagement.

A Call to Presence and Purpose

To live “all in” is not about perfection. It is about intention. It is the daily practice of showing up fully in body, mind, and spirit, in every endeavor. It is refusing the temptation of mediocrity and the comfort of minimal effort. It is about inhabiting each moment with awareness, committing wholeheartedly to chosen paths, and accepting the consequences of those choices with humility and courage.

Life will always present us with opportunities to do things halfway. The harder, but infinitely more rewarding, path is to give ourselves completely to the work before us. To act as owners, not renters, of our time and energy. When we do, we not only elevate the quality of our actions but also the quality of our character. In the end, it is not the number of tasks we complete that defines our lives, but the depth of presence and commitment we bring to them.

References:

Aristotle. (2014). Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. (R. Crisp, Ed.) (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman. https://archive.org/details/selfefficacyexer0000band/page/n5/mode/2up

Confucius. (1997). The analects (D. C. Lau, Trans.). Penguin Classics. https://archive.org/details/theanalectsconfucius

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224927532_Flow_The_Psychology_of_Optimal_Experience

Cásedas, L. (2021). Daniel Goleman and Richard J. Davidson: Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body. Avery, New York, NY, 2017, 336 pp. Mindfulness, 12(9), 2355–2356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01650-4

Laozi. (2009). Tao Te Ching (J. Minford, Trans.). Penguin Books.

Rahula, W. (1974). What the Buddha taught. Grove Press. https://archive.org/details/whatbuddhataught00walp

Taylor, C. (1991). The ethics of authenticity. Harvard University Press.