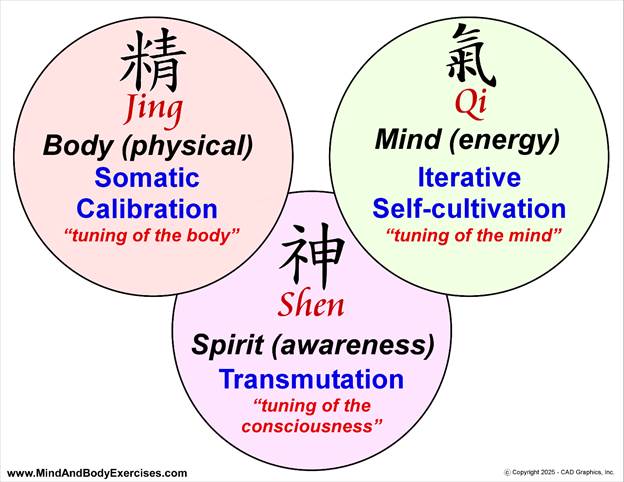

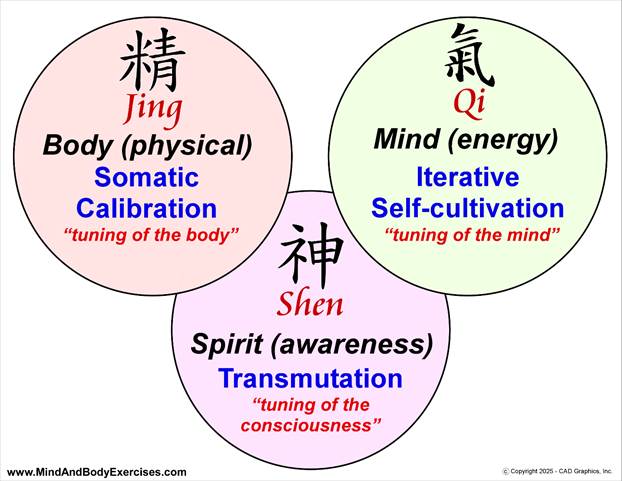

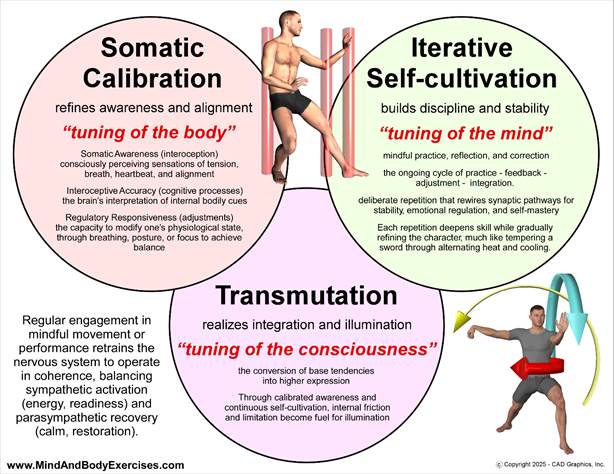

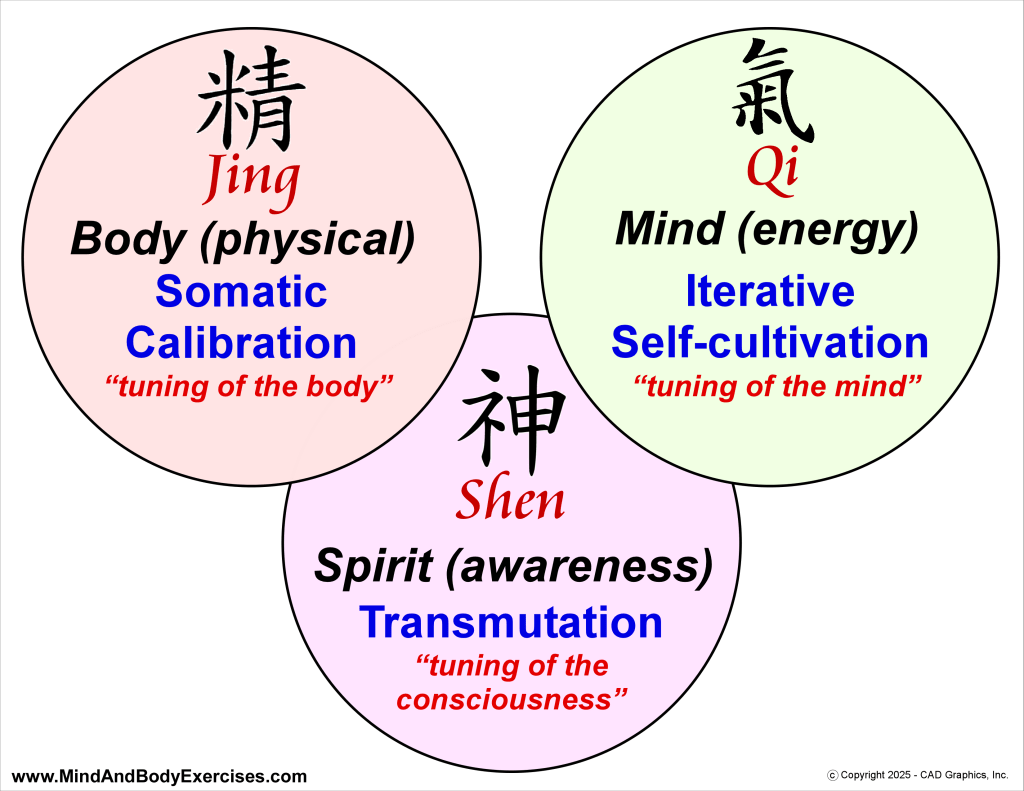

Somatic Calibration

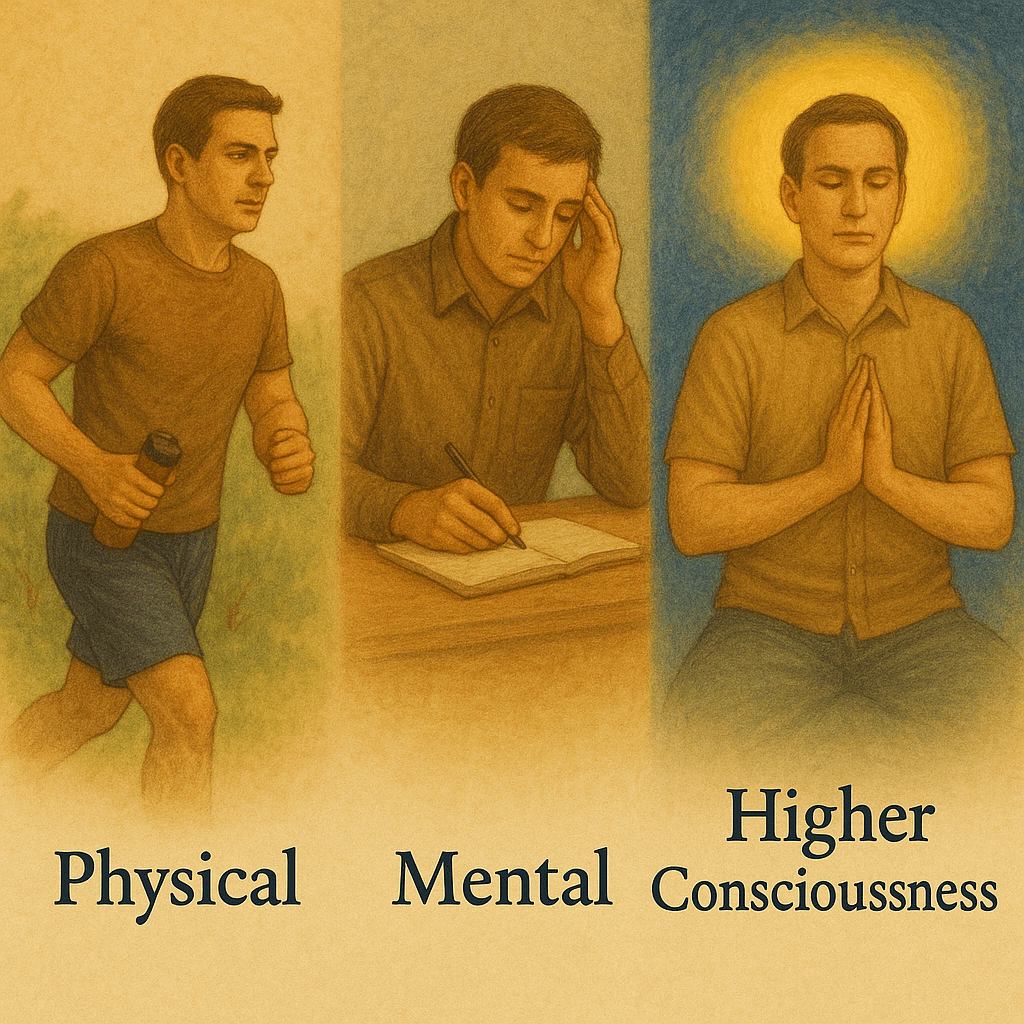

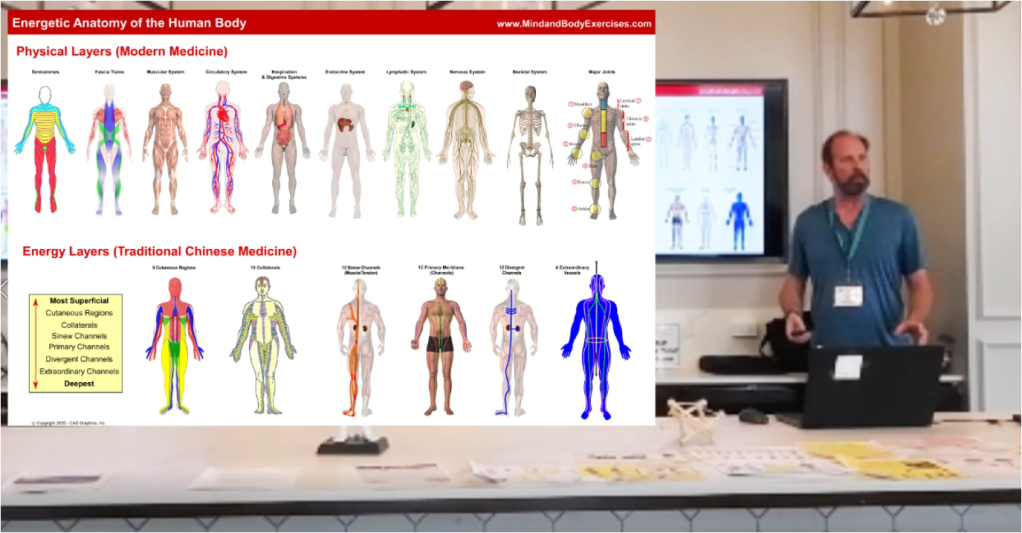

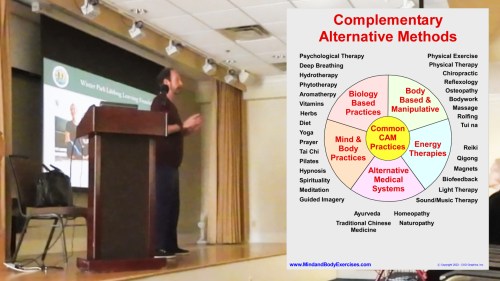

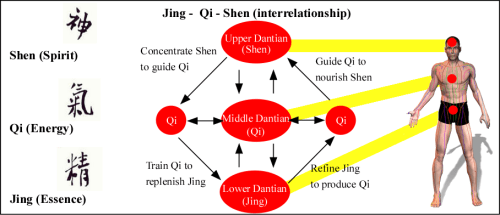

Somatic calibration is the foundational process of aligning body awareness with inner regulation. It involves refining the nervous system’s perception of tension, balance, and breath so the individual can consciously adjust posture, movement, and energetic flow. Through repeated sensory feedback, such as the proprioceptive and interoceptive signals used in qigong, tai chi, or dao yin, the practitioner learns to listen to the body and respond with precision. This phase trains one’s sensitivity and coherence: the capacity to detect micro-imbalances before they manifest as dysfunction.

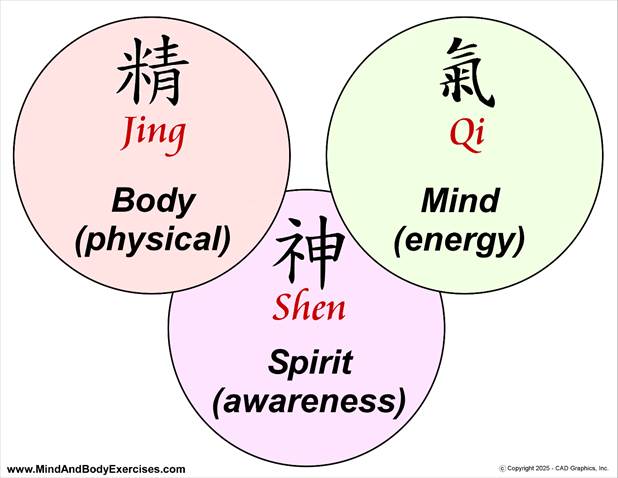

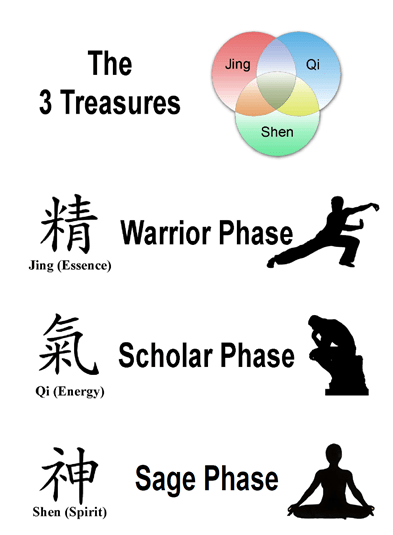

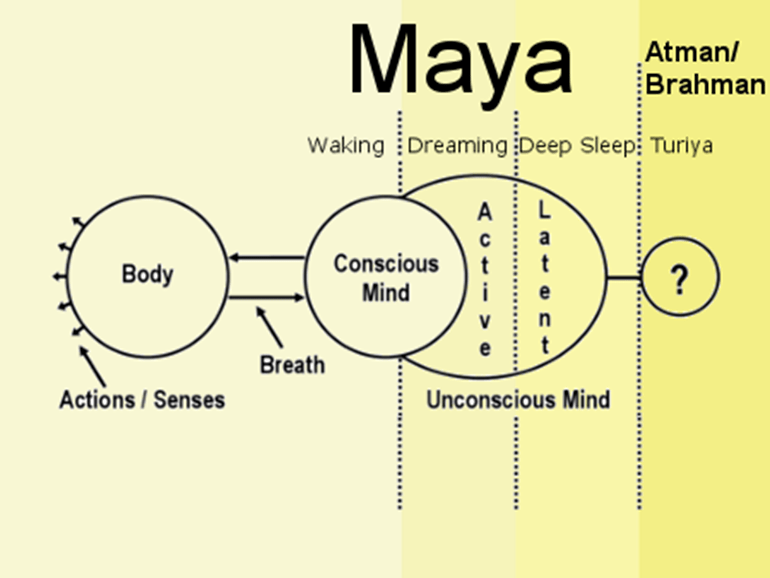

In neurophysiological terms, this process strengthens the communication between the insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and prefrontal regions, the areas responsible for awareness, regulation, and decision-making (Khalsa et al., 2018). In Taoist and martial frameworks, this is the stage of refining jing or the raw essence, by bringing unconscious patterns into conscious alignment.

Iterative Self-Cultivation

Once somatic awareness becomes stable, iterative self-cultivation begins. “Iterative” means cyclical—one polishes the self repeatedly through mindful practice, reflection, and correction. In martial and meditative traditions, this is the ongoing cycle of practice → feedback → adjustment → integration. Each repetition deepens skill while gradually refining the character, much like tempering a sword through alternating heat and cooling.

This process embodies the principle of gongfu (功夫), the disciplined accumulation of effort over time. As the practitioner works through layers of physical, emotional, and cognitive conditioning, they develop what Confucian and Daoist classics call de (virtue or cultivated power). Modern psychology parallels this with neuroplastic adaptation—deliberate repetition that rewires synaptic pathways for stability, emotional regulation, and self-mastery (Davidson & McEwen, 2012).

Transmutation

Transmutation represents the culmination of these iterative refinements, the conversion of base tendencies into higher expression. In Taoist alchemy (neidan), it is the transformation of jing → qi → shen—essence into energy into spirit. Through calibrated awareness and continuous self-cultivation, internal friction and limitation become fuel for illumination.

In practical terms, transmutation is both psychological and energetic. It’s the capacity to metabolize fear into courage, pain into empathy, or adversity into wisdom. Physiologically, such transformation parallels shifts in endocrine and autonomic balance, where once-stressful stimuli now trigger coherence rather than reactivity. Spiritually, it marks the emergence of authenticity and radiant presence, the “light that guides others.”

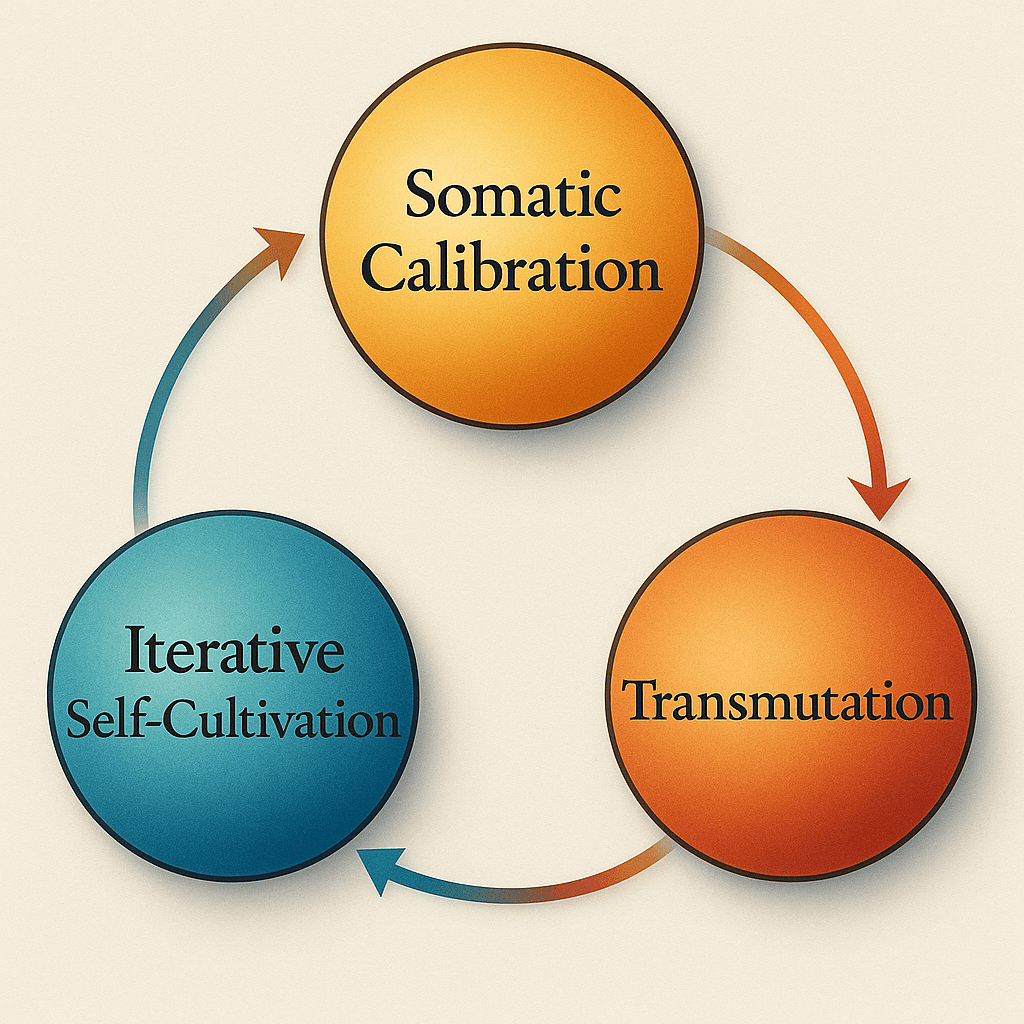

Interconnection of the Three

- Somatic calibration refines awareness and alignment.

- Iterative self-cultivation builds discipline and stability.

- Transmutation realizes integration and illumination.

Together, they form a living spiral rather than a straight line: each turn of cultivation enhances sensitivity (calibration), which allows deeper refinement (iteration), which in turn fuels higher transformation (transmutation). The cycle never ends, but rather it simply ascends toward subtler planes of being.

References:

Davidson, R. J., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nature Neuroscience, 15(5), 689–695. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3093

Khalsa, S. S., Rudrauf, D., Damasio, A. R., & Davidson, R. J. (2018). Interoceptive awareness and its relationship to anxiety, depression, and well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 373(1741), 20170163. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0163