Nei Dan (nae gong, neigong) often translated as “Inner Alchemy,” is one of the most profound and esoteric branches of Daoist cultivation and traditional martial arts training. Unlike Wai Dan (or Wei Dan), or “external alchemy,” which historically referred to concocting elixirs from minerals and herbs, Nei Dan is an internal process of refining and transforming the body’s vital energies (jing, qi, and shen) into higher states of vitality, consciousness, and spiritual realization. This internal alchemical process forms the energetic and philosophical foundation of many advanced martial, meditative, and spiritual practices across Daoist, Chan Buddhist, and certain Confucian lineages.

Historical Origins and Evolution

Daoist Roots (circa 3rd–8th century CE):

Nei Dan emerged from early Daoist cosmology and longevity practices (yangsheng), evolving alongside classical texts such as the Dao De Jing, Zhuangzi, and later the Cantong Qi, (The Seal of the Unity of the Three), often considered the foundational text of internal alchemy (Pregadio, 2019). Early Daoist alchemists saw the human body as a microcosm of the cosmos, mirroring the same dynamic interplay of yin and yang, five elements (wuxing), and celestial cycles. The goal was to harmonize and refine these internal forces to return the practitioner to their original, undifferentiated state (yuan jing, yuan qi, yuan shen).

Tang–Song Dynasty Expansion (7th–13th century):

During the Tang and Song dynasties, Nei Dan was codified into systematic schools such as the Zhong-Lü and Nanzong lineages. These schools emphasized an internal “elixir” (neidan dan) formed through disciplined meditation, breath regulation, and energetic circulation, paralleling the external alchemical metaphor of refining base metals into gold. At this time, martial traditions, especially those influenced by Daoism and Chan Buddhism (e.g., Shaolin and Wudang), began incorporating these principles into their training as a means of enhancing internal power (nei jin), awareness, and longevity.

Integration into Martial Arts (Ming–Qing era onward):

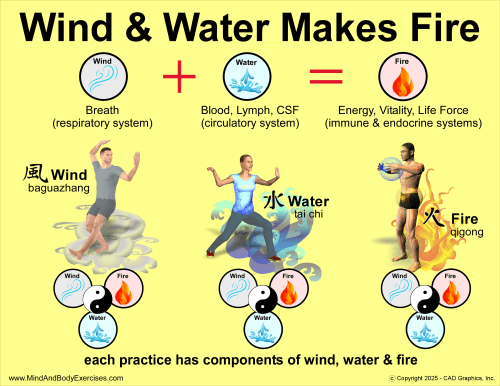

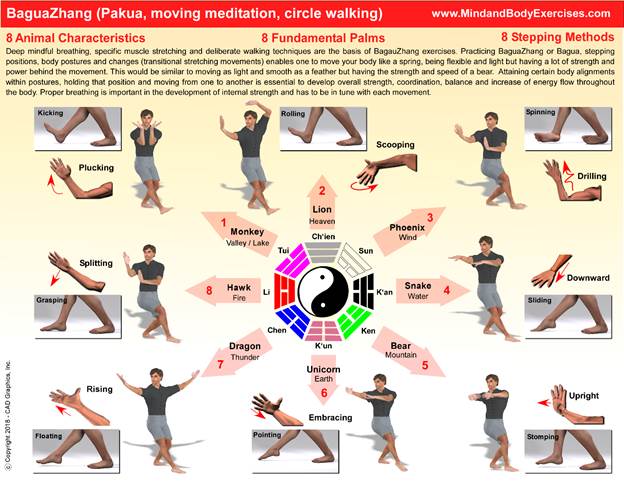

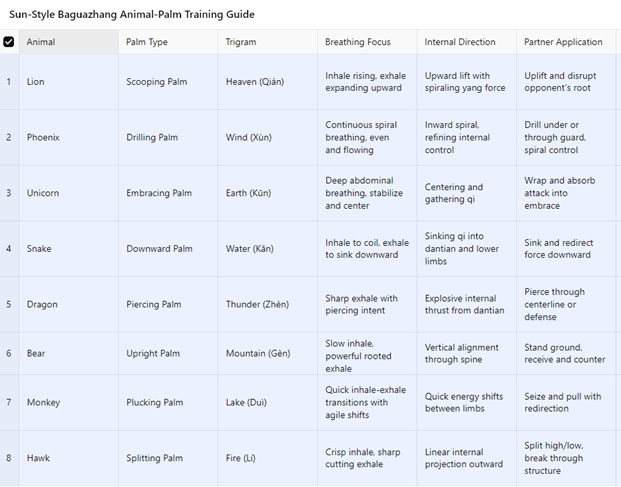

By the late imperial era, Nei Dan principles had become inseparable from Nei Jia Quan (“internal martial arts”) and most notably Taijiquan, Xingyiquan, and Baguazhang. These arts used the body as a vessel for alchemical transformation, with martial techniques functioning as vehicles for energetic refinement and spiritual cultivation. Masters such as Zhang Sanfeng (legendary founder of Taijiquan) and Dong Haichuan (founder of Baguazhang) are often described in Daoist alchemical terms, emphasizing internal stillness, energy transformation, and the unity of movement and spirit.

Core Principles and Goals of Nei Dan

At its essence, Nei Dan is a lifelong path of internal transformation. The traditional Daoist saying — “Refine jing into qi, refine qi into shen, refine shen and return to emptiness” outlines the three fundamental stages:

- Refining Jing:

- Jing refers to “essence” – the foundational life force associated with physical vitality, sexual energy, and genetic potential.

- Practices in this stage focus on conserving and strengthening jing through lifestyle discipline, breath regulation, and daoyin exercises. This builds the “alchemical furnace” in the lower dantian, or the body’s energetic cauldron.

- Transforming Qi:

- Once jing is stabilized, it is “cooked” into qi, which is the vital energy that flows through the body’s meridians.

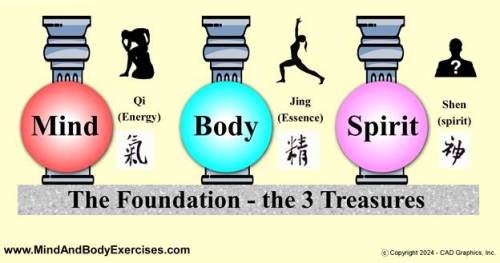

- Breathwork (tu-na), microcosmic orbit circulation (xiao zhoutian), and standing post practices (zhan zhuang) are common methods. Martial expressions of this phase include issuing power (fa jin) and unifying breath with intent (yi qi heyi).

- Refining Shen:

- Shen, or “spirit,” is consciousness itself. At this level, practice aims at expanding awareness, cultivating emptiness (xu), and returning to the primordial source (dao).

- Deep meditation, visualization, and contemplative stillness are central practices, often accompanied by subtle internal energetic processes described metaphorically as “the embryo of immortality” (shen ying).

Practices and Methods Involved

– Breath and Energy Regulation (Tiao Qi):

Controlled breathing (tu-na) is fundamental, teaching practitioners to guide qi consciously through the meridians. The microcosmic orbit (circulating qi along the du and ren vessels) is one of the most well-known techniques.

– Posture and Structure (Tiao Shen):

Postural alignment, rooted stance work (zhan zhuang), and slow, continuous movement (e.g., Taiji or daoyin) build the vessel for qi cultivation. Internal martial arts often hide alchemical work within physical movement.

– Mental Focus and Intention (Tiao Xin):

Training the mind (yi) to direct energy (qi) is central. Practitioners cultivate stillness (jing), intention (yi), and awareness (shen ming), often through visualization of internal alchemical processes.

– Sexual Alchemy (Fangzhong Shu):

Though often misrepresented, sexual alchemy is a legitimate component in many Nei Dan systems. It involves the conservation and refinement of sexual energy (jing), transforming it into spiritual power rather than expending it.

– Meditative and Cosmological Practices:

Advanced practitioners engage in meditations synchronizing their internal rhythms with cosmic cycles (e.g., lunar, solar, and seasonal changes) reflecting the Daoist belief in harmonizing microcosm and macrocosm.

4. Nei Dan in Esoteric Martial Arts

In the context of esoteric martial arts, Nei Dan is not simply health practice, but rather it is a method of refining the warrior’s spirit. The martial applications go far beyond fighting techniques:

- Enhanced Internal Power: Cultivation of nei jin allows practitioners to issue force with minimal muscular effort.

- Heightened Awareness: Refining shen deepens perception, intuition, and responsiveness, essential traits in high-level combat.

- Transformation of Self: Martial practice becomes a vehicle for self-mastery, transcending ego and aligning the individual with the Dao.

Some lineages, such as certain Wudang Daoist sects, Xingyi Nei Gong, or the “Eight Immortal Methods” of Baguazhang, embed Nei Dan principles so deeply that combat forms double as alchemical formulas, guiding practitioners through progressive energetic transformations.

5. Legacy and Contemporary Practice

Today, Nei Dan is studied worldwide, both as a martial discipline and a spiritual science. In modern qigong, taiji, and neigong schools, the terminology may vary — yet the underlying process remains unchanged: the transformation of the human being from a coarse, ordinary state to one of luminous awareness and harmonious unity with the Dao.

It is said in the Daoist classics:

“The elixir is not found in mountains or seas. It is found within one’s own body.”

This aphorism encapsulates the essence of Nei Dan: the human being is the laboratory, the mind is the alchemist, and the Dao is the final elixir.

Nei Dan – Three-Stage Map with Methods, Physiology/Energetics, Goals, and Applications

| Stage / Term | Core Practice Methods | Physiological / Energetic Focus | Alchemical Goal / Transformation | Martial & Spiritual Applications |

| Zhújī / Lìdǐng – Laying the Foundation / Setting the Cauldron | Postural regulation (tiao shen), alignment, pelvic “bowl” set; (zhàn zhuāng), (dǎoyǐn), soft tissue and fascial opening; diet/sleep/seasonal living; moral/intent regulation (de, yi) | Stabilize lower dantian, pelvic floor, diaphragm; vagal tone; fascial tensegrity; Kidney–Spleen axis (TCM); normalize breath mechanics (nasal, low and wide) | Build the “furnace” and “cauldron”; unify body–breath–mind; stop leaks of jing; establish stillness (jing) and attentional continuity | Converts “health qigong” into true alchemical vessel; reliable rooting, joint decompression; baseline nervous-system regulation for higher stages |

| Liàn jīng huà qì – Refine Essence into Qi | (breath work): natural to regulated; (tǔ nà), abdominal “bellows,” Dantian breathing; gentle (jing conservation), menstrual/sexual energy hygiene; light (Kidney tonification) | Consolidate jing in lower dantian; Kidney–Adrenal/endocrine axis; marrow/essence; microcirculation to pelvis/abdomen; perineal lift–release coordination | Transform conserved jing → qi; ignite “furnace fire” without overheating; seal “three leaks” (body, breath, mind) | Increased vitality, recovery, libido stability; root power for internal arts; fatigue resistance; stable base for nèi jìn |

| Xiǎo zhōutiān – Micro-cosmic Orbit | Awareness-led circulation along (Dū, Governing) & (Rèn, Conception) vessels; tongue-to-palate seal; breath–intent coupling; mild bandha/locks analogs | Open Dū/Rèn gates (tailbone, mingmen, jiaji, yintang); diaphragms (pelvic, respiratory, thoracic); cerebrospinal fluid rhythm | Smooth, even qi circulation; harmonize anterior–posterior flow; pressure-equalize cavities; refine coarse sensations to subtle | Reliable whole-body connection; quiet, elastic spine; improved timing/issuing; emotional steadiness under stress |

| Liàn qì huà shén – Refine Qi into Shen | (yì shǒu: guarding with intent), (inner illumination), reverse breathing (when appropriate), long-set, moving-stillness (Taiji, Xingyi, Bagua as vehicles) | Stabilize middle dantian ; heart/pericardium field); regulate Heart–Lung axis; balance sympathetic/parasympathetic tonus; refine channel network | Qi → Shen: transmute vitality into luminosity/clarity; unify (intent–energy–form); stabilize observer-state | Heightened ting jin (listening); anticipatory timing; effortless fa jin; creativity/flow; reduction of startle and fear reactivity |

| Dà zhōutiān – Great Orbit / Grand Circulation | Extend orbit through limbs, twelve primaries, eight extraordinary vessels; seasonal/time-cycle practices; walking-circle meditation (Bagua), long-form Taiji as “moving elixir” | Whole-network perfusion; limb-to-core elastic pathways; periphery–core pressure gradients; integrate Three Jiaos | Global conductivity; unify center–periphery; “breathes as one piece”; refine subtle heat/cool cycles | Issuing from any point/direction whole-body power; resilient gait and spiral force; durable calm under load |

| Liàn shén huán xū – Refine Shen, Return to Emptiness | Silent sitting, formless absorption; (guarding mysterious pass), cessation–contemplation; sleep alchemy (dream/clear-light practice in some lines) | Upper dantian; yintang/niwan field); brain–heart coherence; “spirit residence” clarified; minimize cortical overdrive | Shen → Xu: transparent awareness; stabilize non-dual witnessing; “embryo of immortality” metaphors | Unforced presence, economy of action; fearlessness with humility; “do less, achieve more” in martial timing; ethical clarity |

| Fángzhōng shù – Sexual Alchemy / Temperance | Moderation, timing, and conservation rather than depletion; couple-practice in specific lines; pelvic floor–breath–spine harmonization | Protect jing; endocrine stabilization; avoid sympathetic spikes from excess loss; integrate sensual energy into orbit | Recycle sexual potential into tonic qi and lucid shen; avoid rebound agitation | Stable mood/drive; fewer boom-bust cycles; deep stamina; relational clarity and warmth without clinging |

| Yào huǒhòu – “Fire Phases” / Dosing & Timing | Alternating (civil/martial fire): gentle vs. vigorous practice; periodization across day/season/age; recovery discipline | Prevent overheating/dryness of fluids; protect Heart–Kidney communication; maintain “sweet spot” arousal | Right-dose transformation; steady progress without injury; “water and fire already harmonized” | Sustainable training, fewer plateaus; long career longevity; adaptability across environments |

| Nèiguān jiàoduì – Inner Observation & Corrections | Sensation taxonomy; error recognition (straining, breath holds, scattered mind); teacher feedback, journaling | Detect energy stagnation, “up-flaring,” cold/damp accumulation; posture-breath-mind drift | Keep process safe, reversible, testable; iterate micro-adjustments | Reduces injury/overreach; repeatable skill acquisition; clearer pedagogy for students |

| Déxíng / Jièlǜ – Virtue & Precepts | Ethical commitments, speech discipline, simplicity, gratitude; community of good company | Calms karmic winds; reduces inner conflict/leaks; supports Heart clarity | “Leak-proof” vessel; clarity of intention; congruent life supports practice | Stable leadership presence; conflict de-escalation; trustworthy teacher-student field |

Notes & mini-glossary (for manuscript margin or endnotes)

- Sānbǎo: Jing–Qi–Shen — essence, energy, spirit.

- Three Dantians: lower (vital/structural), middle (affective/relational), upper (cognitive/awareness).

- Micro/Great orbits – conduction along Conception/Governing vessels (small), then through full channel network (great).

- Huǒhòu: “Fire timing” — dosage, intensity, and pacing of practice.

- Nèi jìn: Internal (elastic) power arising from whole-body integration and refined fascia/pressure dynamics.

- Safety: Over-forcing breath, heat, or sexual practices can destabilize mood, sleep, or blood pressure; increase gradually, emphasize recovery.

References:

Despeux, C. (1990). Taoism and Self Cultivation: Transformation and Immortality. In L. Kohn & M. LaFargue (Eds.), Lao-tzu and the Tao-te-ching (pp. 39–52). SUNY Press.

Eskildsen, S. (2008). Daoist Body Cultivation: Traditional Models and Contemporary Practices – Edited by Livia Kohn. Religious Studies Review, 34(3), 230–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0922.2008.00306_4.x

Pregadio, F. (2019). The Seal of the Unity of the Three: A Study and Translation of the Cantong Qi, the Source of the Daoist Way of the Golden Elixir. Golden Elixir Press.

Robinet, I. (1993). Taoist Meditation: The Mao-shan Tradition of Great Purity. State University of New York Press.

Yang, J. M. (2005). The Root of Chinese Qigong: Secrets of Health, Longevity, & Enlightenment. YMAA Publications. https://archive.org/details/rootofchineseqig0000yang