A Detailed Summary to Daoist Alchemy from Chinese and Korean Internal Arts

Traditional Chinese internal arts offer a rich system of physical, energetic, and spiritual practices. Key concepts include Wei Dan (外丹), Qigong (气功), and Nei Dan (内丹). Understanding these three terms alongside their Korean martial arts parallels, clarifies important distinctions in the pursuit of health, self-mastery, and spiritual growth.

Wei Dan (外丹) – External Alchemy

Definition: “Outer Elixir.” Wei Dan refers to ancient Daoist alchemical practices that sought to create physical elixirs for longevity or immortality by processing minerals and herbs externally (Pregadio, 2018).

Methods: Involves chemical experimentation with substances like mercury, arsenic, and cinnabar, (often highly toxic) which were ingested or used topically in pursuit of physical immortality.

Goals: Attain longevity or immortality by altering the body through external means.

Philosophy: Belief that the secrets of life and transformation can be discovered and harnessed in the material world outside the practitioner, reflecting an outward search for transcendence.

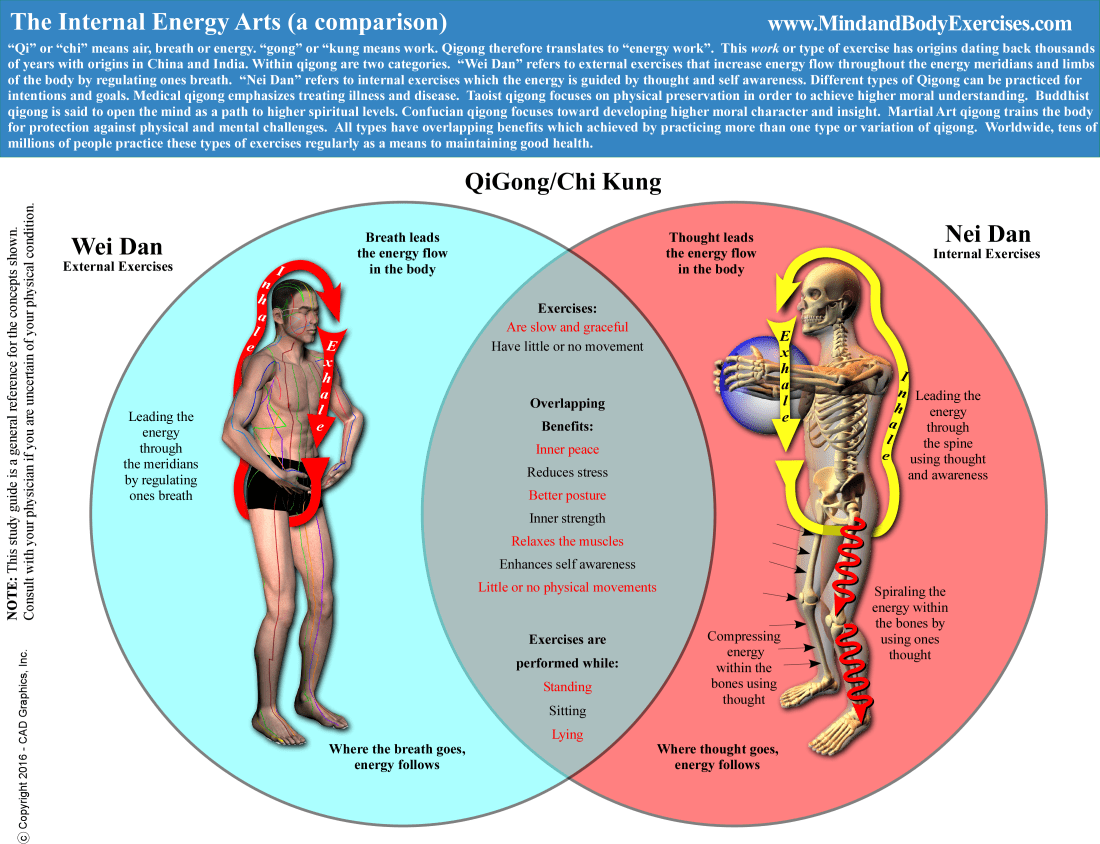

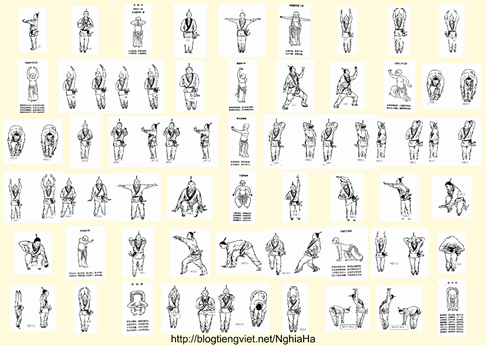

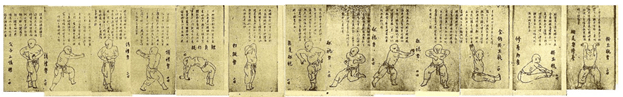

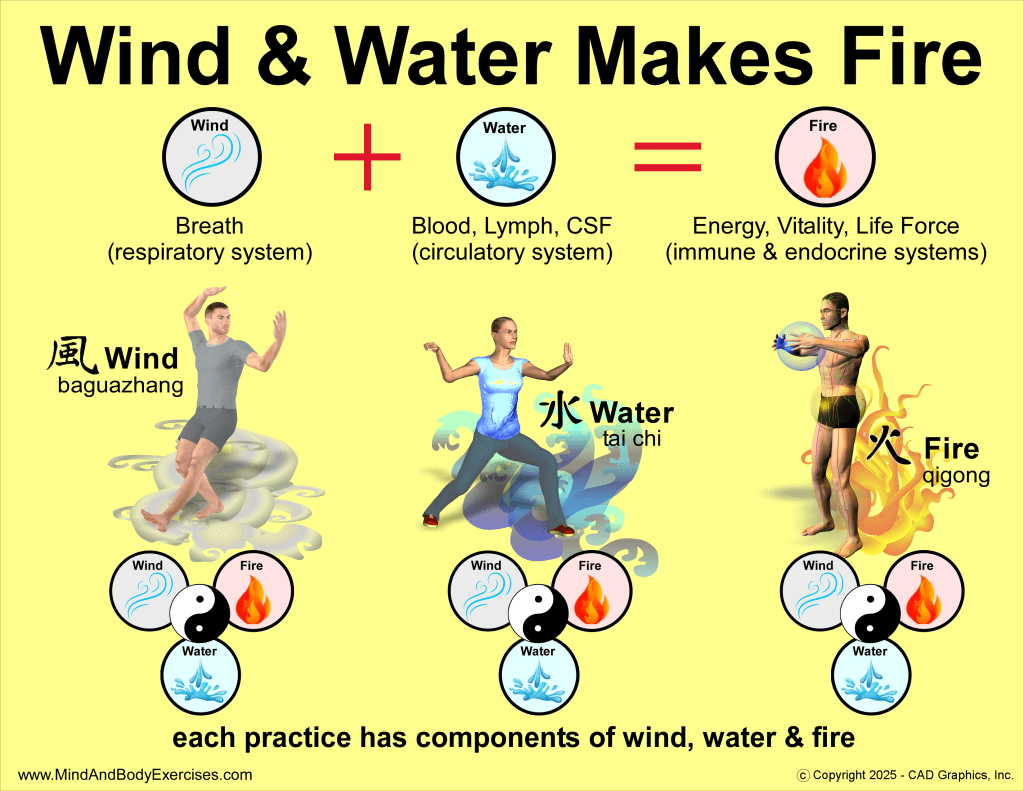

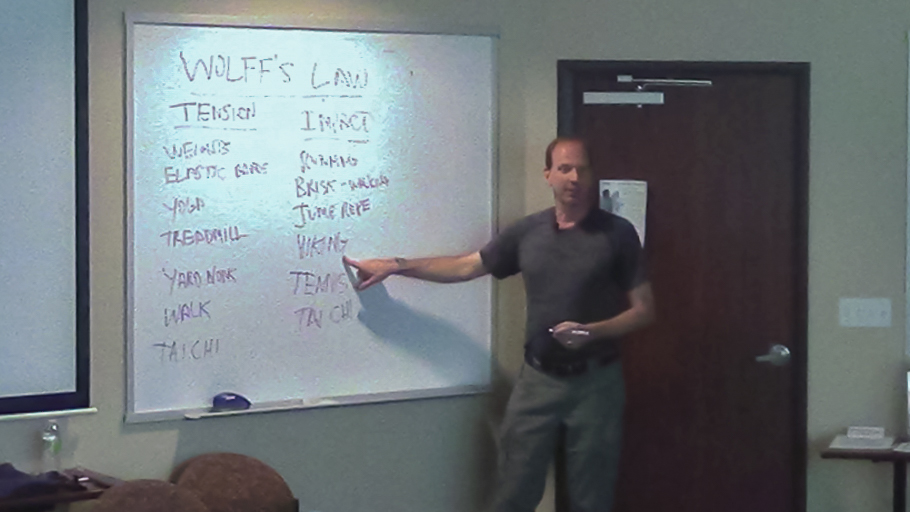

Qigong (气功) – Energy Skill

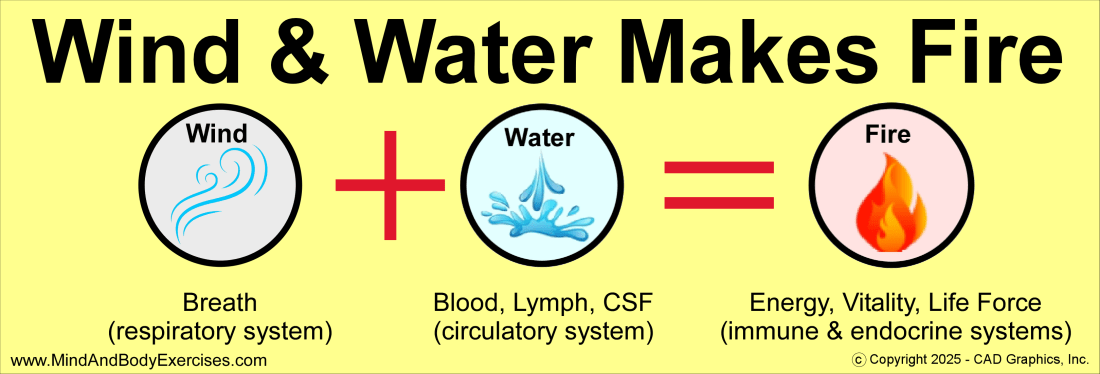

Definition: “Energy Work.” Qigong encompasses practices that combine breath control, movement, visualization, and meditation to regulate and cultivate qi, the vital energy believed to animate life (Jahnke, 2002).

Method: Includes dynamic routines (e.g., Ba Duan Jin), static postures (e.g., Zhan Zhuang), breath regulation, and mental focus to circulate qi along the body’s meridians.

Goals: Promote health, increase vitality, balance emotions, and prepare body and mind for advanced practices.

Philosophy: The human body is a microcosm of the universe, and by harmonizing breath, movement, and mind, practitioners align themselves with natural laws (Yang, 1997).

Nei Dan (内丹) – Internal Alchemy

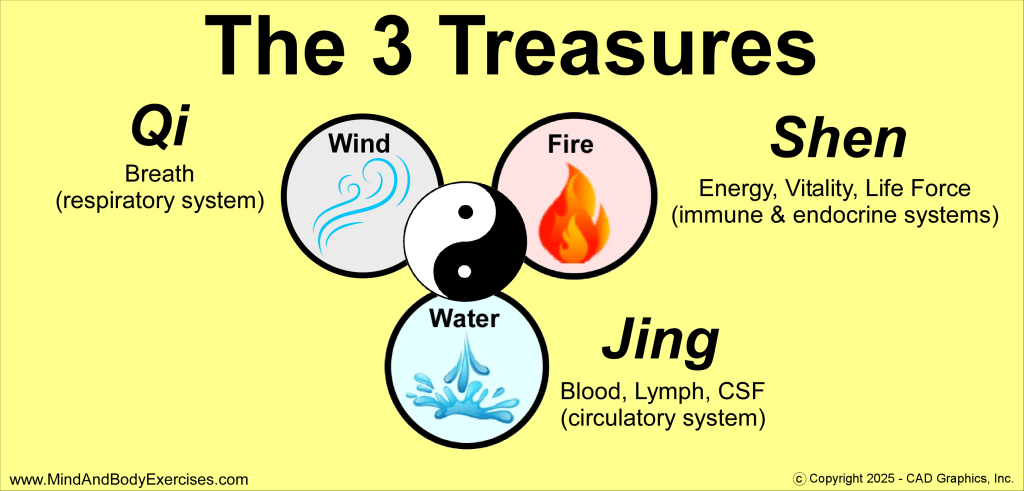

Definition: “Inner Elixir.” Nei Dan is the highest level of Daoist internal cultivation, dedicated to refining one’s essence (jing), energy (qi), and spirit (shen) through advanced meditative and energetic practices (Mitchell, 2011).

Method: Involves breath retention, microcosmic orbit meditation, sexual energy control, visualization of energy flows, and progressive transformation of jing → qi → shen → emptiness (xu).

Goals: Achieve spiritual immortality, realization of one’s true nature, and union with the Dao.

Philosophy: Transformation must occur internally; by purifying one’s own mind-body-spirit, practitioners embody the Daoist ideal of returning to original emptiness and harmony with the cosmos.

Comparing Chinese and Korean Terms

Korean martial arts use similar-sounding terms of Wae Gong, Gi Gong, and Nae Gong, which overlap but don’t always match the Chinese Daoist meanings:

| Korean Term | Hangul / Hanja | Similar Chinese Concept | Same Practice? | Notes |

| Wae Gong | 외공 / 外功 | Wei Dan (外丹) | No | Refers to physical conditioning in martial arts, not Wei Dan’s alchemy |

| Gi Gong | 기공 / 氣功 | Qigong 气功 | Yes | Practices are nearly identical; focuses on breath, energy, and movement |

| Nae Gong | 내공 / 內功 | Nei Dan 内功 | Partially | Internal energy work similar to Nei Gong; not necessarily advanced Nei Dan alchemy (Yang, 2007). |

Etymological Breakdown of Chinese Characters

Understanding the roots of the Chinese characters deepens appreciation of these arts:

- 外 (Wài): 6 strokes. Components 夕 (evening) + 卜 (divination) → symbolizes seeking knowledge outside oneself.

- 气 (Qì): 4 strokes. Ancient forms depict swirling vapor → breath, vital energy.

- 内 (Nèi): 4 strokes. 冂 (enclosure) + 人 (person) → shows a person inside boundaries → introspection.

These etymologies reflect core Daoist themes of balancing inside (内) and outside (外), and cultivating qi (气) to align with the Dao (Qiu, 2000).

Integrated Comparison Table

| Aspect | Wei Dan (外丹) | Qigong (气功) | Nei Dan (内丹) |

| Meaning | External elixir/alchemy | Energy skill/cultivation | Internal elixir/alchemy |

| Method | Chemical concoctions | Breath, movement, meditation | Advanced meditative transformation |

| Goal | Physical immortality | Health, vitality, stress relief | Spiritual immortality/enlightenment |

| Korean Parallel | Wae Gong (not equivalent) | Gi Gong (equivalent) | Nae Gong (partially equivalent) |

Conclusion

Wei Dan, Qigong, and Nei Dan represent distinct layers of Daoist health and spiritual practices: Wei Dan’s external focus, Qigong’s energy cultivation, and Nei Dan’s profound internal alchemy. Meanwhile, Korean martial arts terms like Wae Gong, Gi Gong, and Nae Gong reflect overlapping ideas but emphasize martial conditioning, energy work, and internal strength, respectively.

Understanding these differences empowers practitioners to choose a path aligned with their goals, whether health, martial skill, or spiritual awakening.

References

Jahnke, R. (2002). The Healing Promise of Qi: Creating Extraordinary Wellness Through Qigong and Tai Chi. Contemporary Books.

Mitchell, D. (2011). Daoist Nei Gong: The Philosophical Art of Internal Alchemy. Singing Dragon

Pregadio, F. (2018). The Taoist Alchemy: Nei Dan and Wei Dan in Chinese Tradition. Golden Elixir Press.

Qiu, X. (2000). Chinese Writing. The Society for the Study of Early China & The Institute of East Asian Studies.

Yang, J. M. (2007). Qigong for Health & Martial Arts: Exercises & Meditation. YMAA Publication Center.

Note: I could find no single authoritative English-language source compiling the terminology of Wae Gong, Gi Gong, and Nae Gong. These terms are part of Korean martial arts oral traditions and school teachings, with meanings overlapping but not identical to the Chinese concepts discussed here.