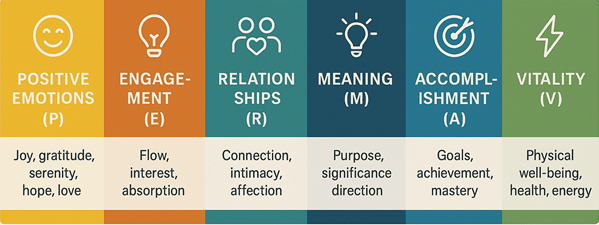

Dr. Martin Seligman, one of the founders of positive psychology, introduced the PERMA model as a framework to describe and cultivate human flourishing. PERMA outlines five measurable pillars of well-being:

- Positive Emotions

- Engagement

- Relationships

- Meaning

- Accomplishment (Seligman, 2011).

In subsequent years, scholars and practitioners expanded the model by adding a sixth dimension with Vitality, to better account for physical health and energetic capacity as essential to overall well-being (Kern et al., 2020).

Together, the PERMA-V model offers a comprehensive approach to understanding psychological, social, emotional, and physical well-being.

Positive Emotions (P)

Positive emotions include joy, gratitude, serenity, hope, and love. Research shows that experiencing positive emotions broadens attention, enhances creativity, builds psychological resilience, and supports long-term well-being (Fredrickson, 2013). Seligman (2011) emphasizes that these emotions are not momentary feelings but foundations of a flourishing life.

Engagement (E)

Engagement refers to being fully absorbed in an activity, often described as “flow” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Flow experiences occur when personal skill meets challenge, producing deep involvement, loss of self-consciousness, and intrinsic reward. Higher levels of engagement correlate with improved well-being, productivity, and life satisfaction (Hone et al., 2014).

Relationships (R)

Human well-being is deeply social. Supportive relationships increase life satisfaction, protect against depression, and contribute to healthy longevity (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). Seligman (2011) identifies positive relationships as one of the strongest predictors of thriving across the lifespan.

Meaning (M)

Meaning involves belonging to and serving something larger than oneself—such as family, community, faith, service, or purpose-driven work. Purpose and meaning are associated with greater resilience, better health outcomes, and increased life satisfaction (Steger, 2012).

Accomplishment (A)

Accomplishment refers to the pursuit and achievement of goals, mastery, and personal growth. Research indicates that setting meaningful goals and progressing toward them enhances agency, motivation, and long-term well-being (Locke & Latham, 2019).

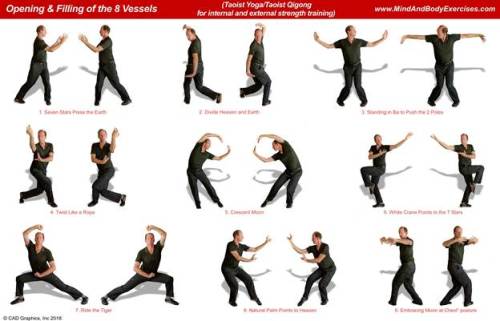

Vitality (V)

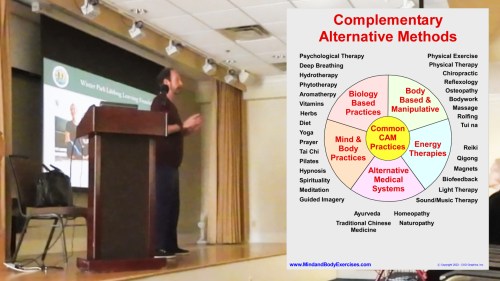

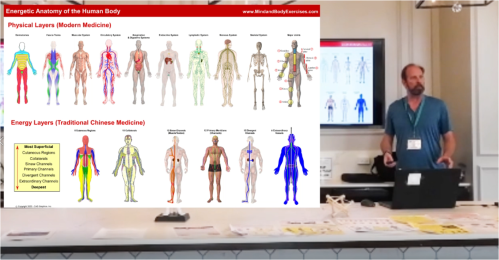

Vitality represents physical energy, health, and the sense of being alive and vibrant. Emerging literature supports physical well-being as an essential dimension of flourishing, leading to the addition of “V” to the PERMA framework in many academic and applied settings (Kern et al., 2020). Vitality includes:

- energy levels

- sleep quality

- nutrition

- movement and exercise

- resilience and metabolic health

This component reinforces the interconnected nature of mind and body, supporting the broader shift toward integrative models of well-being.

The PERMA-V framework expands Seligman’s original model to reflect a more complete picture of human flourishing. Positive emotions, deep engagement, supportive relationships, meaningful purpose, ongoing accomplishments, and a foundation of physical vitality operate synergistically to support long-term well-being. Because each element is measurable and developable, individuals, educators, clinicians, and organizations can intentionally use PERMA-V as a roadmap for cultivating resilience, health, and a flourishing life.

| Element | Definition | Key Features / Indicators | Examples |

| P – Positive Emotions | Experiencing uplifting emotional states that broaden thinking and build resilience. | Joy, gratitude, serenity, hope, love | Gratitude practice, enjoying nature, humor |

| E – Engagement | Deep involvement or “flow” in meaningful tasks. | Time distortion, skill–challenge balance, intrinsic reward | Creative work, martial arts forms, problem-solving |

| R – Relationships | Supportive, authentic, and meaningful social connections. | Belonging, trust, communication, social support | Family bonds, community ties, friendships |

| M – Meaning | Having purpose and belonging to something greater than oneself. | Values alignment, service, contribution | Teaching, spirituality, volunteer work |

| A – Accomplishment | Pursuing and achieving goals, mastery, and personal growth. | Discipline, progression, competence | Skill development, certifications, physical training milestones |

| V – Vitality | Physical health, energy, and foundational well-being of the body. | Sleep quality, nutrition, movement, resilience | Exercise, breathing practices, mind–body exercises |

References:

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224927532_Flow_The_Psychology_of_Optimal_Experience

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Hone, L. C., Jarden, A., Schofield, G. M., & Duncan, S. (2014). Measuring flourishing: The impact of operational definitions on the prevalence of high levels of well-being. International Journal of Wellbeing, 4(1), 62–90. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v4i1.4

Kern, M. L., Williams, P., Spong, C., Colla, R., Sharma, K., Downie, A., & Taylor, J. A. (2020). Systems informed positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(6), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2019). The development of goal setting theory: A half century retrospective. Motivation Science, 5(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000127

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press. https://archive.org/details/flourish0000seli

Steger, M. F. (2012). Making meaning in life. Psychological Inquiry, 23(4), 381–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2012.720832