Human beings have long sensed that the deepest layer of existence is not found in linear time, external circumstance, or the physical body, but in the silent, witnessing presence that experiences them all. The ancient spiritual insight that “it has always been now” suggests that consciousness is not bound to the past or future but resides permanently in the living immediacy of the present moment. When this insight is expanded, it evokes a larger metaphysical possibility: that consciousness may be primary, timeless, and eternal, briefly expressing itself through human form. Though such a claim seems philosophical or mystical, aspects of Christian theology and modern quantum physics unexpectedly converge with this view when interpreted through their deepest lenses.

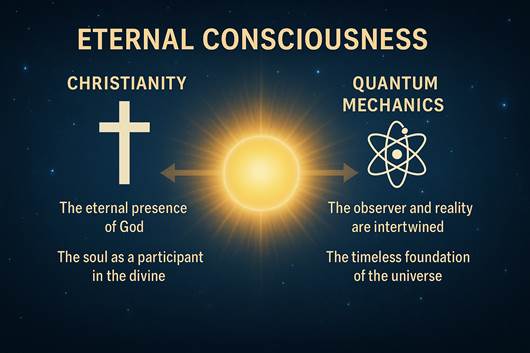

The Christian Understanding of Eternal Presence

Christian theology has long affirmed a form of “eternal present” that is foundational to the nature of God. Saint Augustine famously argued that time itself is a created dimension, and that God exists in an unchanging, timeless “Now” (Augustine, trans. 2008). This aligns with the scriptural assertion that in God, “there is no variation or shadow of turning” (James 1:17, NRSV), emphasizing a dimension of being where temporality does not apply.

Christ Himself uses the language of timeless identity: “Before Abraham was, I AM” (John 8:58). This statement echoes Exodus 3:14 of “I AM THAT I AM,” suggests a divine consciousness that is eternally present rather than confined to sequential time. The Apostle Peter supports this when he writes, “With the Lord one day is like a thousand years, and a thousand years are like one day” (2 Peter 3:8). These passages collectively reveal a clear theological framework: God is not simply everlasting but eternally present, existing beyond linear time.

Christian mystics expand this further. Meister Eckhart taught that the soul has a “spark” capable of experiencing God in the Eternal Now (Eckhart, trans. 1981). St. John of the Cross described the innermost self as a “lamp of the Lord” (echoing Proverbs 20:27) that perceives God in stillness. Brother Lawrence emphasized continual awareness of God’s presence in the present moment (Lawrence, 1982). These traditions view consciousness, particularly the silent witness within, as the point of contact between the human person and the eternal presence of God.

From a Christian perspective, then, the idea of “eternal consciousness residing temporarily in form” aligns closely with biblical anthropology: humanity receives life through the divine breath (Genesis 2:7), exists in God (Acts 17:28), and returns to God at death (Ecclesiastes 12:7). This is not pantheism, nor a denial of individuality, but a recognition that the human spirit participates in the timeless presence of God.

The Quantum Universe: Time, Observation, and Non-Locality

While Christianity approaches timelessness through theology, quantum physics approaches it through the structure of reality. Einstein’s theory of relativity first challenged the assumption of flowing time, proposing instead that past, present, and future coexist in a four-dimensional spacetime “block” (Einstein & Infeld, 1938). Physicists now widely refer to the “block universe” or eternalism, an interpretation in which time is a dimension we move through, not something that moves through us.

Quantum mechanics deepens this mystery.

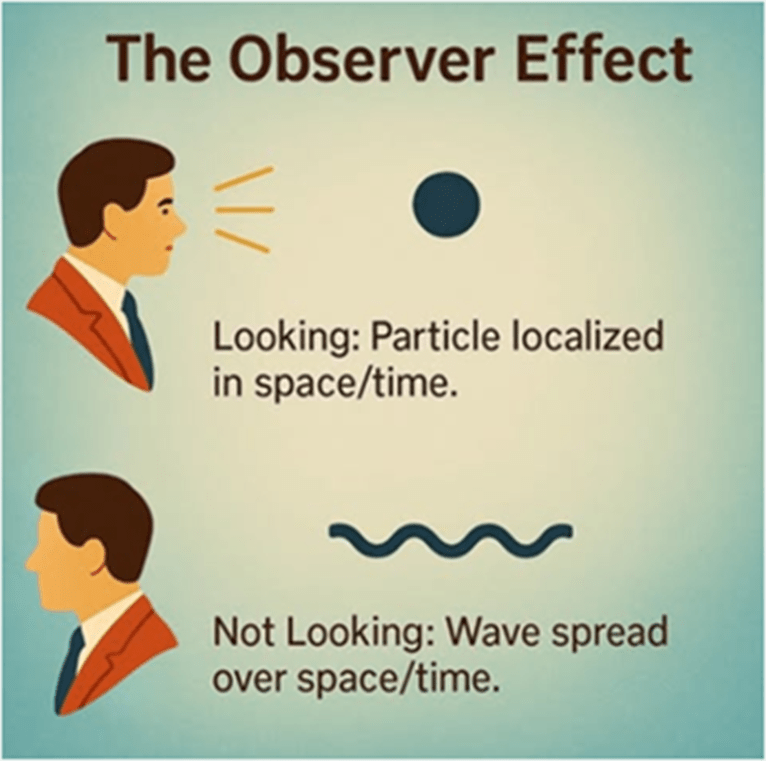

1. The Observer and the Measurement Problem

In quantum theory, particles exist in a probabilistic superposition until measured. But what ends the superposition?

John von Neumann (1955) demonstrated mathematically that purely physical systems cannot complete a measurement; the chain of interaction must eventually terminate in a non-physical observer, traditionally interpreted as conscious awareness. Nobel physicist Eugene Wigner argued that consciousness plays a direct role in determining physical reality (Wigner, 1961). This does not mean “mind creates reality,” but it strongly suggests that consciousness is not an accidental byproduct of matter but rather it is woven directly into the act of manifestation.

2. Non-Locality and the Unity of Reality

Bell’s Theorem and subsequent experiments (Aspect et al., 1982) revealed that particles separated even by great distances behave as a single, non-local system. This implies that the universe is fundamentally interconnected, not composed of isolated parts. This resembles the idea of one underlying field or ground of being, expressing itself as many forms.

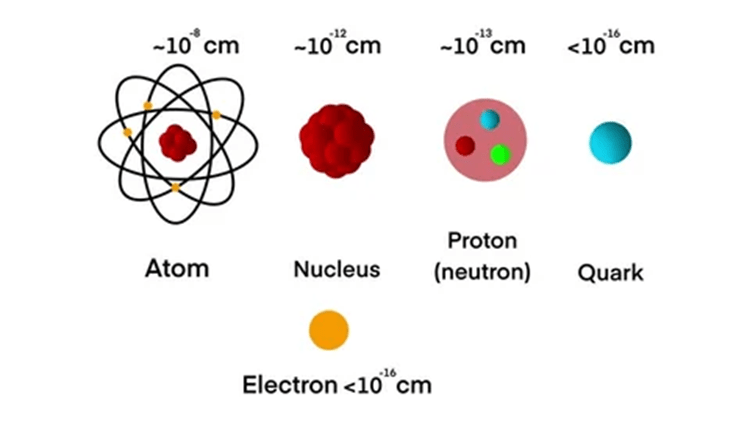

3. The Quantum Vacuum and Emergence of Form

Quantum field theory proposes that what we call “empty space” is in fact a powerful field of potentiality known as the zero-point field, from which all particles emerge (Davies & Brown, 1988). Matter is not fundamental; fields are. Some physicists, including David Bohm, likened this underlying order to a deeper, implicate reality (Bohm, 1980). This parallels the concept of eternal consciousness: a formless ground that expresses temporary forms.

4. The Participatory Universe

John Archibald Wheeler’s “participatory anthropic principle” boldly declared:

“Observers are necessary to bring the universe into being.”

(Wheeler, 1989)

In other words: consciousness is not in the universe; the universe is participatory with consciousness.

Crossing the Bridge: Where Christianity and Quantum Physics Meet Eternal Consciousness

While Christianity and quantum mechanics differ in language and purpose, both suggest that:

- Physical time is not fundamental.

- Reality is not purely material.

- Observation/consciousness interacts with the structure of reality.

- The deepest layer of being is unified and timeless.

- Human consciousness participates in something larger.

Christianity interprets this as the human spirit participating in the eternal presence of God.

Quantum mechanics interprets this as the observer participating in the manifestation of quantum events.

Both perspectives converge on a central point:

Consciousness is not merely the product of matter; it is involved in the structure of reality itself.

Neither field proves “eternal consciousness,” but both make it philosophically and scientifically plausible. The Christian view gives consciousness an eternal source (God), while quantum physics removes mechanistic constraints and reveals a universe that is deeply relational, non-local, and dependent on observation.

When understood at depth, Christianity and quantum physics do not conflict with the idea of eternal consciousness. Instead, they illuminate it from different angles. Christianity describes a divine, timeless presence in which the human spirit participates. Quantum physics reveals a universe that is non-material at its foundation, observer-dependent, and timeless in structure. Together, these perspectives support the philosophical insight that consciousness may be fundamental as an eternal presence momentarily experiencing itself through human form, always now, always here.

References:

Aspect, A., Grangier, P., & Roger, G. (1982). Experimental realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm Gedankenexperiment: A new violation of Bell’s inequalities. Physical Review Letters, 49(2), 91–94. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.49.91

Augustine. (2008). Confessions (H. Chadwick, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published ca. 397 CE) https://archive.org/details/confessions0000augu_k5u5

Bohm, D. (1980). Wholeness and the implicate order. Routledge & Kegan Paul. http://www.gci.org.uk/Documents/DavidBohm-WholenessAndTheImplicateOrder.pdf

Davies, P. C. W., & Brown, J. (Eds.). (1988). The ghost in the atom: A discussion of the mysteries of quantum physics. Cambridge University Press. https://archive.org/details/ghostinatomdiscu0000davi

Eckhart, M. (1981). The essential sermons, commentaries, treatises and defense (E. Colledge & B. McGinn, Trans.). Paulist Press.

Einstein, A., & Infeld, L. (1938). The evolution of physics. Cambridge University Press. https://archive.org/details/evolutionofphysi033254mbp/page/n9/mode/2up

Lawrence, Brother. (1982). The practice of the presence of God. Whitaker House. (Original work published 1693)

von Neumann, J. (1955). Mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics (R. T. Beyer, Trans.). Princeton University Press.

Wheeler, J. A. (1989). Information, physics, quantum: the search for links. https://philarchive.org/rec/WHEIPQ

Wigner, E. P. (1961). Remarks on the mind–body question. In I. J. Good (Ed.), The scientist speculates (pp. 284–302). Heinemann.