Turning Bodily Awareness into Conscious Regulation

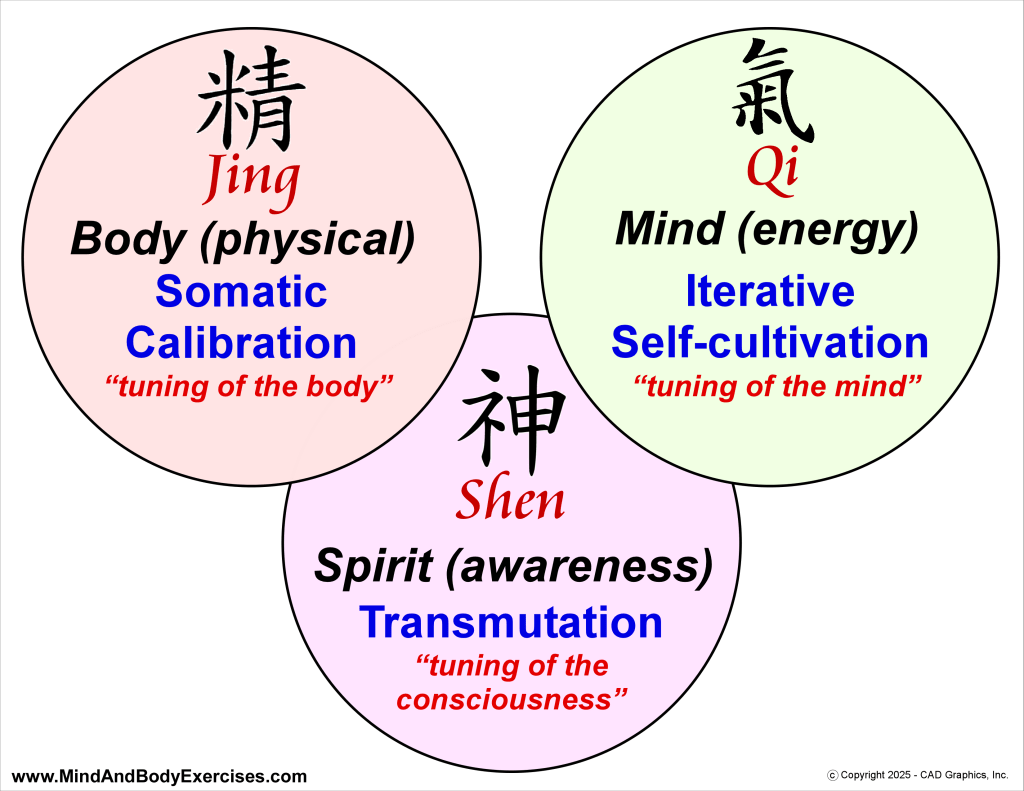

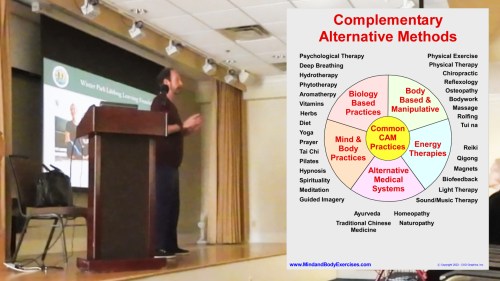

Across disciplines of psychology, physiology, and embodied practice, there is growing recognition that the body is not merely a vessel for the mind. The physical body is an active participant in perception, emotion, and cognition. The emerging concept of somatic calibration describes the process by which a person develops refined awareness of internal bodily states (interoception), interprets them accurately, and adjusts posture, movement, or breath to maintain physical and psychological balance. This calibration is literally, “bringing the body into tune” and is essential for resilience, emotional regulation, and well-being (Fogel, as cited in Taylor, 2023). It can be deliberately trained and strengthened through mind–body disciplines such as yoga, qigong, tai chi, and baguazhang, as well as through musical and kinesthetic arts that require fine motor control, proprioceptive precision, and mindful attention.

Understanding Somatic Calibration

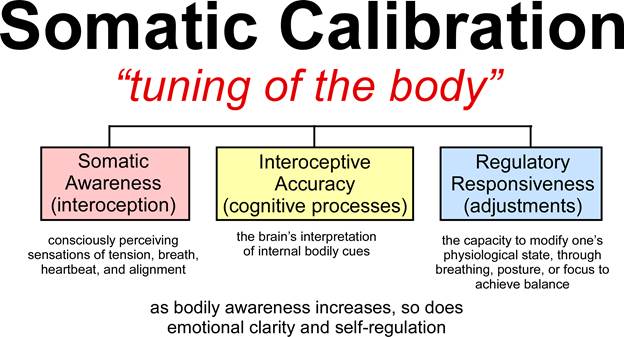

Somatic calibration merges three interdependent processes: somatic awareness, interoceptive accuracy, and regulatory responsiveness. Somatic awareness involves consciously perceiving sensations of tension, breath, heartbeat, and alignment. Interoception represents the brain’s interpretation of internal bodily cues, mediated largely by the insula and anterior cingulate cortex (Khalsa et al., 2018). Regulatory responsiveness describes the capacity to modify one’s physiological state—through breathing, posture, or focus to achieve balance.

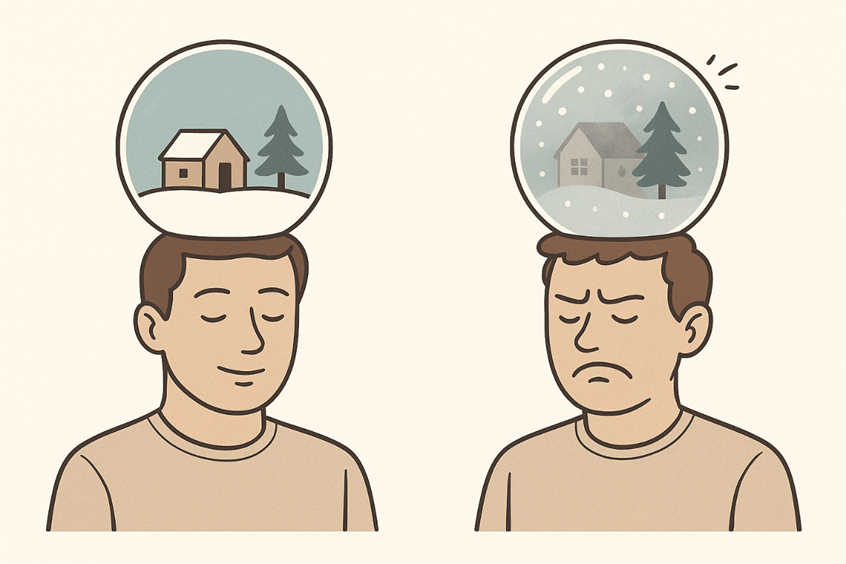

When an individual becomes proficient in these domains, they can effectively tune their body like an instrument, sensing when they are “out of tune” (stressed, fatigued, tense) and adjusting accordingly. Somatic calibration thus serves as a biofeedback loop connecting the physical and psychological realms: as bodily awareness increases, so does emotional clarity and self-regulation (Mehling et al., 2011).

Mind–Body Practices as Tools of Calibration

Yoga and Interoceptive Refinement

Yoga has long been recognized as a powerful practice for enhancing somatic awareness. Through sustained postures (āsanas), controlled breathing (prāṇāyāma), and meditative attention (dhyāna), practitioners learn to inhabit the body more fully, developing both interoceptive sensitivity and cognitive calm. Research shows that yoga increases vagal tone and improves regulation of the autonomic nervous system, thereby enhancing both physiological and emotional stability (Streeter et al., 2012). In the context of somatic calibration, yoga acts as a systematic alignment practice, and a method of perceiving subtle internal feedback from muscles, joints, and breath to fine-tune both movement and mind.

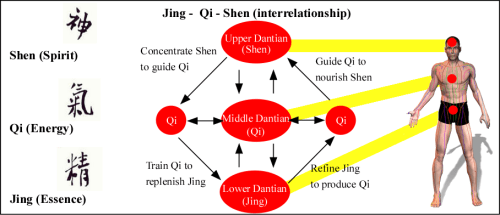

Qigong, Tai Chi, and the Subtle Body

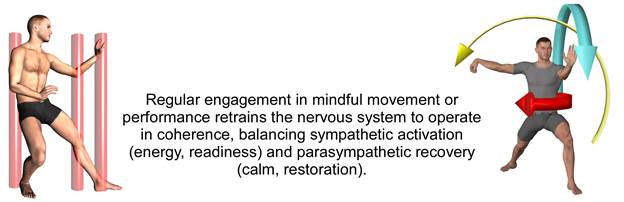

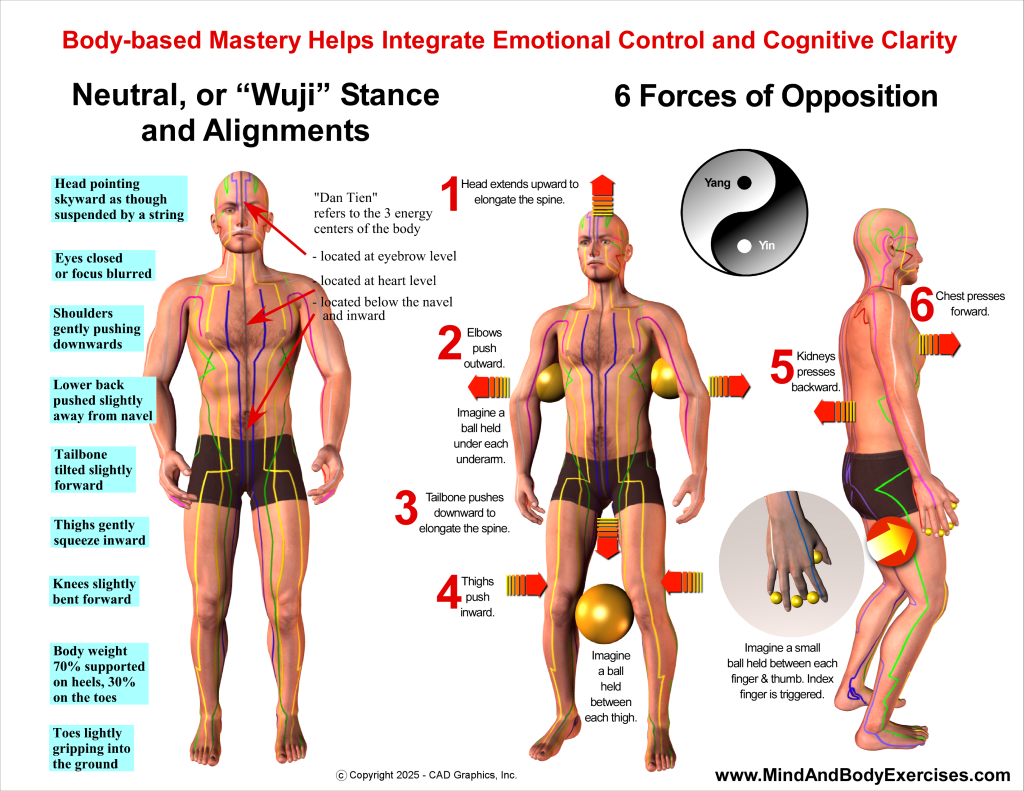

Qigong and tai chi, rooted in Traditional Chinese Medicine, emphasize the coordinated movement of qi (vital energy) through the body’s meridian pathways. These practices require precise synchronization of breath, posture, and intention (yi), creating a cyclical feedback between proprioceptive and interoceptive systems (Jahnke et al., 2010). Tai chi and qigong improve kinesthetic sensitivity and help practitioners perceive micro-adjustments in balance, muscular tension, and internal energy flow, all core aspects of somatic calibration. A meta-analysis by Wayne et al. (2014) found that tai chi enhances balance, proprioception, and body awareness in older adults, while also reducing anxiety and depression, demonstrating how refining body mechanics concurrently refines emotional and mental regulation.

Baguazhang and Dynamic Calibration

Among the Chinese internal martial arts, BaguaZhang (Eight Trigram Palm) represents a dynamic, circular system of continuous transformation. Its spiraling steps, shifting weight, and changing palm positions require constant micro-adjustment of the spine, hips, and limbs. This active calibration of movement with breath and intention cultivates adaptive interoceptive intelligence, or the ability to sense and modulate physiological responses during complex motion. Internal martial arts like baguazhang promote “somatic intelligence,” where awareness, movement, and perception operate as one. Each turning step becomes a moment of recalibration strives to balance yin and yang, tension and release, stillness and motion.

Martial Arts as Applied Somatic Discipline

Beyond the meditative aspects, martial arts more broadly embody somatic calibration through functional stress-testing. The practitioner learns to manage fear, aggression, and arousal through breath and structure, while maintaining equilibrium under pressure. Studies show that martial arts training enhances proprioceptive acuity, sensorimotor coordination, and self-regulation (Lakes & Hoyt, 2004). This aligns with modern somatic psychology’s premise that body-based mastery helps integrate emotional control and cognitive clarity. Each strike, stance, or transition offers an opportunity to refine how the nervous system responds to stress, literally training the body-mind to self-regulate in motion.

Playing Musical Instruments and Fine Motor Calibration

Somatic calibration extends beyond movement disciplines into musicianship and performance arts, which demand acute proprioceptive and interoceptive tuning. Professional musicians display higher sensorimotor awareness, cortical plasticity, and fine-motor coordination than non-musicians (Herholz & Zatorre, 2012). Learning an instrument requires sensing pressure, breath, timing, and resonance, developing a nuanced relationship between internal cues and external feedback. In this way, musical practice mirrors somatic calibration: constant attunement between perception and output, between inner signal and outer sound.

Mechanisms of Mind–Body Calibration

The unifying mechanism underlying all these disciplines lies in sensorimotor feedback loops that strengthen awareness and adaptability. Regular engagement in mindful movement or performance retrains the nervous system to operate in coherence, balancing sympathetic activation (energy, readiness) and parasympathetic recovery (calm, restoration). Slow, deliberate movement is characteristic of tai chi or yoga and allows the practitioner to perceive otherwise subtle cues such as joint angle, muscle tone, or internal vibration. As these perceptions sharpen, the practitioner gains conscious influence over states that were once automatic, such as tension, breath rate, or postural asymmetry (Mehling et al., 2011).

Through repeated practice, this refined self-perception translates into emotional and cognitive domains. For instance, noticing a tightening diaphragm before anxiety arises offers a chance to intervene somatically to slow the breath and prevent escalation. This is the essence of somatic calibration: turning bodily awareness into conscious regulation.

Somatic calibration represents a modern articulation of ancient principles: that self-mastery begins with bodily awareness. By refining perception and control of internal processes, one cultivates a harmonious relationship between the body and mind. Practices such as yoga, qigong, tai chi, and baguazhang, as well as musical training and other precise movement arts, can act as living laboratories for this process. They transform awareness into action, and action into alignment.

Ultimately, somatic calibration is not limited to therapy or training, but rather it is a lifelong practice of attuning to the ever-changing signals of one’s internal and external environment. In a world that often prioritizes cognition over embodiment, somatic calibration restores equilibrium, offering a path toward resilience, integration, and inner harmony.

References:

Herholz, S. C., & Zatorre, R. J. (2012). Musical training as a framework for brain plasticity: Behavior, function, and structure. Neuron, 76(3), 486–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.011

Jahnke, R., Larkey, L., Rogers, C., Etnier, J., & Lin, F. (2010). A comprehensive review of health benefits of qigong and tai chi. American journal of health promotion : AJHP, 24(6), e1–e25. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.081013-LIT-248

Khalsa, S. S., Adolphs, R., Cameron, O. G., Critchley, H. D., Davenport, P. W., Feinstein, J. S., … Paulus, M. P. (2018). Interoception and mental health: A roadmap. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(6), 501–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.12.004

Lakes, K. D., & Hoyt, W. T. (2004). Promoting self-regulation through school-based martial arts training. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(3), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2004.04.002

Mehling, W. E., Price, C., Daubenmier, J., Acree, M., Bartmess, E., & Stewart, A. (2011). The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA). PLoS ONE, 7(11), e48230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048230

Streeter, C. C., Gerbarg, P. L., Saper, R. B., Ciraulo, D. A., & Brown, R. P. (2012). Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Medical Hypotheses, 78(5), 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021

Taylor, J. (2023). What is somatic awareness? Retrieved from https://janetaylor.net/what-is-somatic-awareness/

Wayne, P. M., & Yeh, G. Y. (2014). Effect of Tai Chi on cognitive performance in older adults: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62(1), 25–39. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24383523/