“When the waters settle, the reflection is clear; when stirred, the light is scattered.” – Taoist proverb

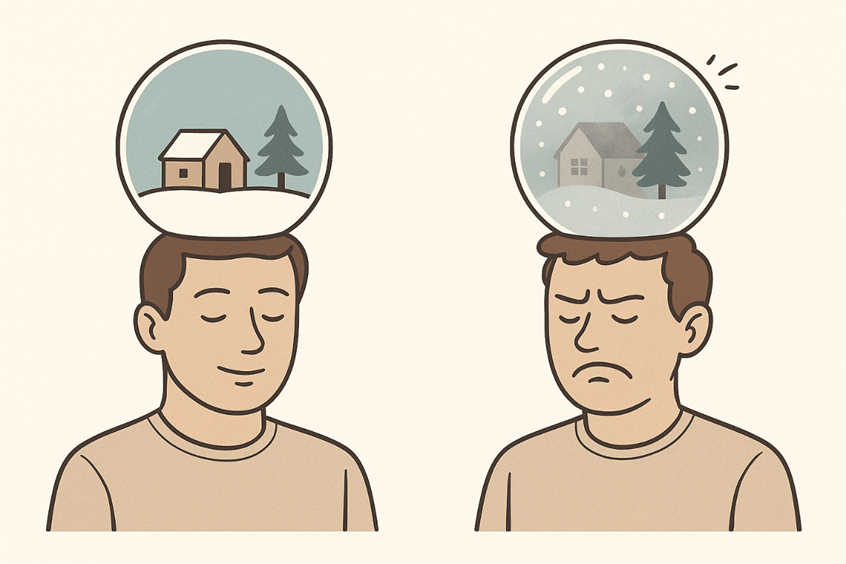

The human mind can be likened to a Christmas snow globe. When resting in stillness, it is calm and transparent, revealing its contents clearly. When shaken, the glittering particles obscure the view until motion ceases and calm returns. In much the same way, the human mind loses clarity when it is agitated by thought, emotion, or distraction. Yet, when stillness is restored, insight becomes visible again.

This analogy is ancient in spirit though modern in form. Taoist, Buddhist, and contemplative traditions have long taught that the unsettled mind is filled with “ten thousand thoughts” and is like muddy water that cannot reflect the sky. When the water is left alone, sediment sinks and the surface becomes clear, mirroring reality without distortion. Neuroscience has since confirmed that mental agitation disrupts attentional networks and self-regulation, whereas calm awareness engages prefrontal regions that enhance clarity and emotional balance (Vago & Silbersweig, 2016).

Agitation, Clarity, and the Nature of Mind

Just as the snowflakes in a globe swirl when shaken, so do thoughts and emotions when the mind is disturbed by stress, fear, or overstimulation. The more one reacts, the longer the “flakes” take to settle. Mindfulness teacher Jillian Pransky (2023) uses this same metaphor to describe how meditation allows the inner “snow” to fall to rest and thus revealing stillness and depth beneath the surface.

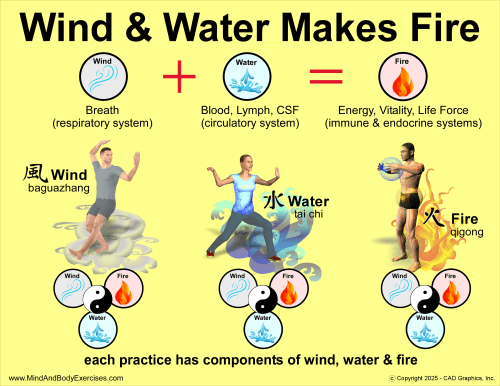

In a similar vein, meditation research shows that repeated exposure to calm awareness enhances the brain’s ability to disengage from habitual thinking and recover from agitation (Fox et al., 2016). Thus, stillness is not passivity; it is active regulation, a physiological return to balance. This capacity for returning to center is what Tai Chi and Qigong practitioners seek to cultivate daily.

The Snow Globe and the Internal Arts

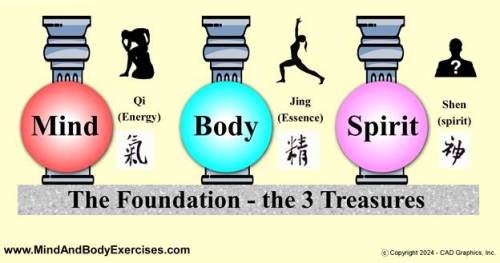

In Qigong and Tai Chi, movement arises from stillness and returns to it. Between each form lies a subtle pause or an internal settling. When agitation arises, practitioners are taught to “let the mind sink to the dantian,” mirroring how snow settles to the bottom of the globe. Breath slows, the nervous system calms, and the clarity of awareness expands.

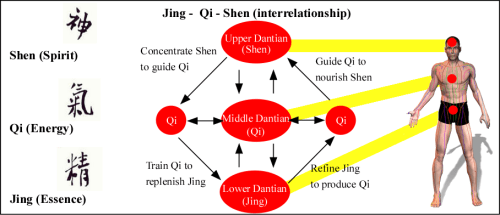

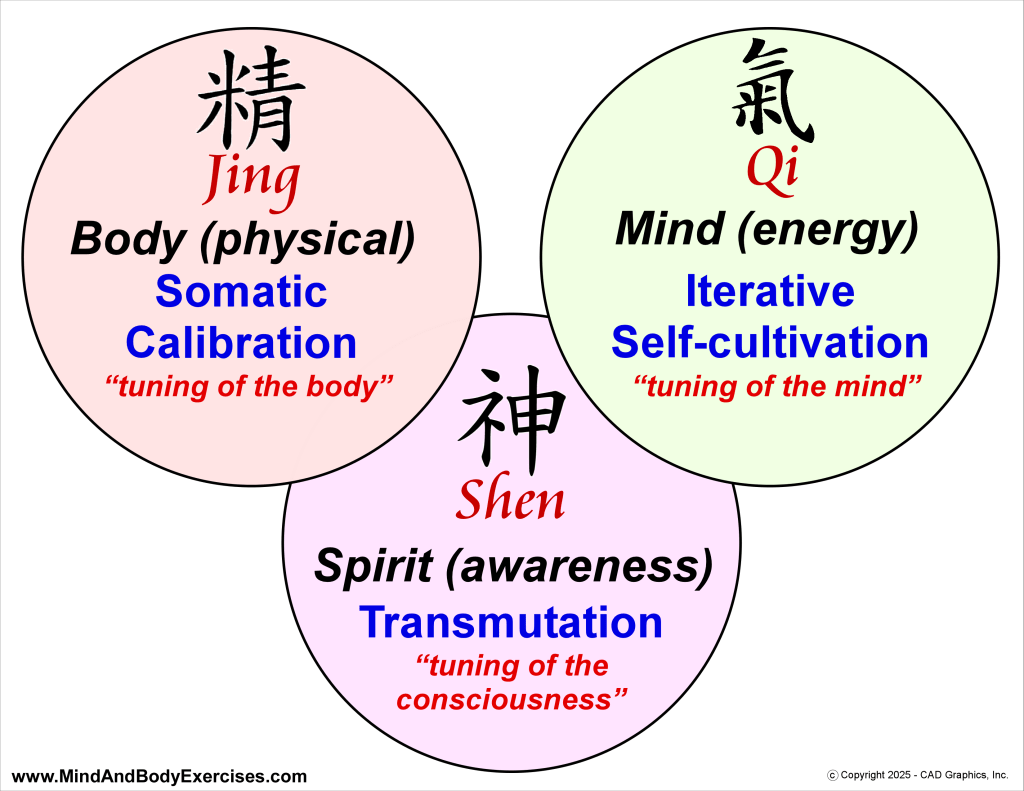

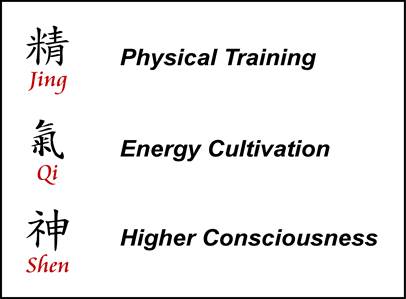

Daoist classics such as the Qingjing Jing emphasize this principle: “If the mind is pure and still, all things will become clear of themselves” (Li, 1981). Stillness (jing) is not an absence of life but the foundation for transformation. Without it, internal energy (qi) becomes scattered, and consciousness (shen) clouded. With it, harmony between body, breath, and mind is restored, a concept echoed in modern psychophysiology as “parasympathetic dominance,” when calm awareness stabilizes physiological rhythms (Mayo Clinic, 2023).

From this lens, the snow globe becomes a teaching instrument:

- The glass represents the body—transparent but containing.

- The water symbolizes consciousness.

- The flakes represent thoughts, memories, and emotions.

- The base is the dantian—the center of gravity, both physical and spiritual.

When the practitioner “shakes” with stress or emotion, the particles rise and obscure vision. When stillness returns, the scene or the true nature of mind becomes visible once again.

Table: Mind States vs. Snow-Globe States

| Aspect | Snow Globe State | Mind State Equivalent | Practical Cultivation Method |

| Unsettled | Shaken; snow whirling chaotically | Agitated thoughts, anxiety, scattered focus | Pause; deep diaphragmatic breathing; grounding awareness in body |

| Settling | Flakes gradually fall | Thoughts subside; awareness re-centers | Gentle movement; slow Qigong; rhythmic breathing |

| Still | Water clear and unmoving | Calm mind; perceptual clarity; inner balance | Meditation; standing post; mindful observation |

| Re-agitated | Globe shaken again | Emotional disturbance or overstimulation | Recognize trigger; respond with patience and non-reactivity |

| Restored Clarity | Scene visible again | Insight, creativity, emotional regulation | Continued practice of calm-abiding (samatha) and mindful awareness |

Embodied Awareness and the Settling of Qi

In Tai Chi, teachers often say, “Where the mind goes, qi follows.” When the mind is disturbed, the qi scatters; when the mind is calm, qi gathers. The settling of mental “snow” mirrors the condensation of energy within the body’s core. The nervous system reflects this change: heart rate variability improves, cortisol decreases, and attention stabilizes (Fox et al., 2016; Mayo Clinic, 2023).

This internal stillness is not a withdrawal from life, but rather it is refinement. It allows the practitioner to perceive without distortion and to respond without haste. It is what the Zen tradition calls mushin, “no-mind,” where thought does not vanish but becomes transparent and responsive rather than turbulent (Li, 1981). The snow globe thus offers a contemporary bridge between contemplative science and ancient practice, a visualization of how calm leads to wisdom.

Transmutation Through Stillness

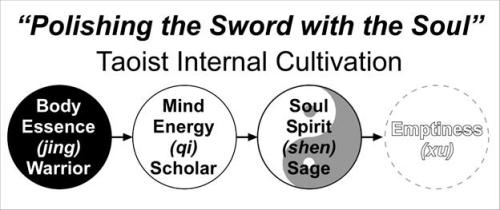

The deeper message of this metaphor lies in transformation. When one repeatedly allows the snow to settle, a new pattern of being forms. Neural pathways shift; emotional reactivity decreases; intuition sharpens. In Taoist alchemy, this is nei dan or the refinement of essence (jing) into energy (qi), and energy into spirit (shen). What begins as calming the surface mind evolves into inner transmutation or the awakening of clarity that is no longer dependent on circumstance.

Therefore, to train the mind is not to eliminate its contents but to see through them, to let every swirl of snow reveal rather than obscure. Through stillness, awareness refracts light instead of scattering it. Through daily practice, one learns to set down the globe and simply watch the snow fall.

“The mind once still is capable of reflecting heaven and earth.” – Zhuangzi

References:

Fox, K. C. R., Dixon, M. L., Nijeboer, S., Girn, M., Lifshitz, M., Ellamil, M., Sedlmeier, P., & Christoff, K. (2016). Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A review and meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.06342. https://arxiv.org/abs/1603.06342

Fox, K. C. R., Kang, Y., Lifshitz, M., & Christoff, K. (2016). Increasing cognitive-emotional flexibility with meditation and hypnosis: The cognitive neuroscience of de-automatization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.03553. https://arxiv.org/abs/1605.03553

Li, J. (1981). Qingjing Jing (清靜經): The Scripture of Clarity and Stillness. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. https://archive.org/details/daoist-scripture-qing-jing-jing-louis-komjathy/QJJ%20-%20Louis%20Komjathy%20%28Editor%29/

Mayo Clinic. (2023, December 14). Meditation: A simple, fast way to reduce stress. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/meditation/in-depth/meditation/art-20045858

Pransky, J. (2023, June 11). a meditation to create space in the midst of chaos — jillian pransky. Jillian Pransky. https://www.jillianpransky.com/blog/creating-space-snowglobe-meditation

Vago, D. R., & Zeidan, F. (2016). The brain on silent: mind wandering, mindful awareness, and states of mental tranquility. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1373(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13171