Tempering the Self – Cultivation through Pressure, Refinement and Purpose

In the tradition of martial arts and Taoist self-cultivation, the process of becoming a person of refined character, resilience and integrity is often portrayed metaphorically as a transformation under pressure or through rigorous refinement. Just as coal under intense pressure becomes a diamond, as glass is tempered to strengthen it, or as a sword is heated, hammered and folded until it offers purity, sharpness and endurance, so too does the aspirant put themselves through trials, reflection, disciplined training, and “taking apart” of habitual patterns in order to emerge stronger, clearer, and more whole. This essay explores that metaphorical terrain, linking historic Taoist concepts of cultivation with martial-art training and moral growth.

At the heart of the metaphor is the notion of pressure and refinement. A lump of coal, subjected to geological force over time, becomes a diamond: the original material has been compressed, purified, and transformed into something far harder and more brilliant. In a similar way, a glass object is heated and rapidly cooled (tempered) so that its structure changes, the internal stresses are intentionally introduced, then stabilized and thus the glass becomes more resistant to shattering. A sword likewise must be heated, hammered, folded, quenched, and polished; the metal structure is reorganized so that it can hold an edge, bend without breaking, and serve a purpose. Transposed to human character and training, these metaphors suggest that to become something more than we currently are, we must face pressure (external challenges, internal struggle), go through the restructuring of habit, belief, body and mind, and emerge in a usable state: strong, resilient, sharp of focus, yet tempered by insight.

In essence, this process represents a kind of transmutation, orthe transformation of one’s coarse, unrefined nature into a state of inner clarity and integrity. Just as physical elements change state under heat or pressure, the human psyche and spirit can evolve through disciplined practice and self-reflection. In Taoist internal alchemy, such transmutation marks the transition from density to subtlety, from the crude to the luminous.

In the realm of martial arts, and particularly those influenced by Taoist philosophy, this is not merely a nice poetic image, but an embedded structure of training. The discipline, repetition, discomfort, unlearning of ingrained patterns, and gradual internalization of principles all function like the hammer and heat of the swordsmith. As one trains, one is literally breaking down old neural/structural patterns of body and mind, refining them, and integrating them into something more coherent, more “whole” and more aligned with one’s higher potential.

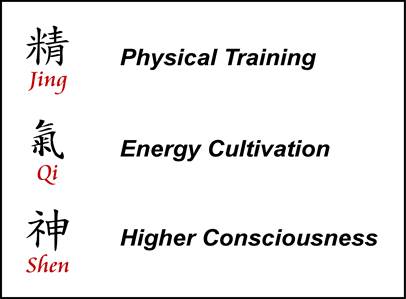

From the viewpoint of Taoist self-cultivation, this process aligns with the paradigm of internal alchemy (neidan). Internal alchemy is described as a “transformation process that involves changing both body and mind to higher levels of functioning” (Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism, 2025). According to Taoist doctrine, one works with the “Three Treasures” (jing → qi → shen: essence, energy, spirit) and seeks gradual refinement of self (Wikipedia contributors, 2025). The aim is to dissolve coarse patterns (the raw coal), to apply “heat” and “pressure” in the sense of rigorous practice, moral confrontation, endurance, discipline, and then to emerge as something sharper, lighter, more refined, aligned with the Tao (道). This dynamic mirrors the alchemical notion of transmutation, in which base material (lead or raw essence) is refined into gold or spiritual purity. Taoist cultivation translates this symbolism into physiological and psychological terms: jing (essence) transmuted into qi (vital energy), and qi into shen (spirit), forming a continuum of self-refinement that bridges body, mind, and consciousness (Needham, 1983; Pregadio, 2019).

I prefer the metaphor of “if you want to know what is inside something, you squeeze it; if you want to know what something is made of, you take it apart and hopefully put it back together, maybe even better than the original.” In the training context, “squeeze” refers to tests and trials: one’s character is squeezed by adversity, by training drills, by mental stress. That brings to awareness hidden weaknesses of unseen fractures, untempered spots. “Taking apart” refers to the deconstruction of habit, belief, movement, reaction: in the martial arts one often unlearns bad posture, reflexes, tension, and rebuilds structure. Then one reassembles with new alignment, better structure, refined intent. The final state is not merely restored but upgraded, like a sword folded multiple times becomes stronger than the original billet; glass tempered is stronger than annealed glass; coal stressed in pressure becomes diamond.

In ethical or moral self-cultivation this means that facing one’s character under pressure reveals hidden fissures: impulsiveness, reactivity, unresolved fear, habit. Good training (physical, mental, moral) allows one to “see” those fissures, to let them be “heated” (examined, confronted) and “hammered” (repeated disciplined practice, correction) until the structure of self becomes more resilient, more integrated, more responsive rather than reactive. The Taoist culture encourages a kind of return to one’s original nature of goodness (德, de) and compassion, which has been obscured by life’s conditioning (Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism, 2025). The “sword” or “diamond” of self-character thus is not about hardness for its own sake, but a resilient clarity, readiness, humility, and refined responsiveness.

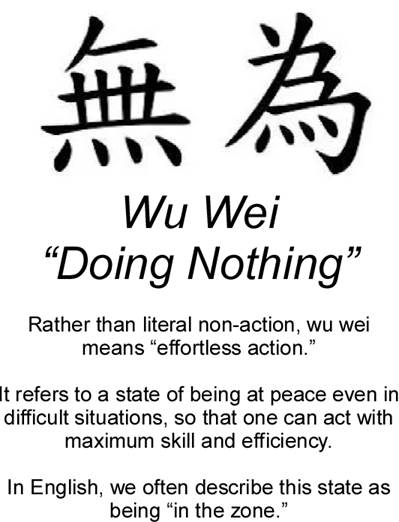

Moreover, the metaphor highlights the paradox: we often think that pressure or challenge is purely negative; yet in transformation systems, from geology to metallurgy to glass tempering, pressure and heat are required for refinement. In martial practice, avoidance of stress means never getting the internal re-working that occurs under challenge. In Taoist cultivation, the path is not easy but transformation. Indeed, the Taoist ideal of wú wéi or “effortless action” is often misunderstood; it is not doing nothing, but acting naturally from a well-tempered, integrated being (Wikipedia contributors, 2025). After the hammering, the sword is sharp without forced strength; the tempered glass resists shatter without brittle rigidity; the diamond shines because prior pressure created its internal perfection.

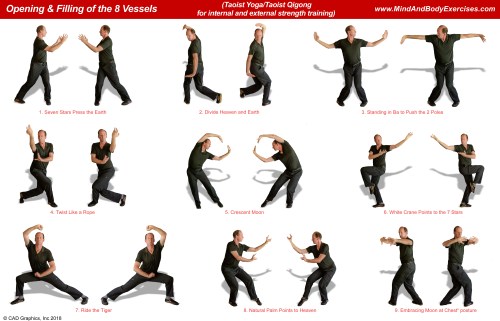

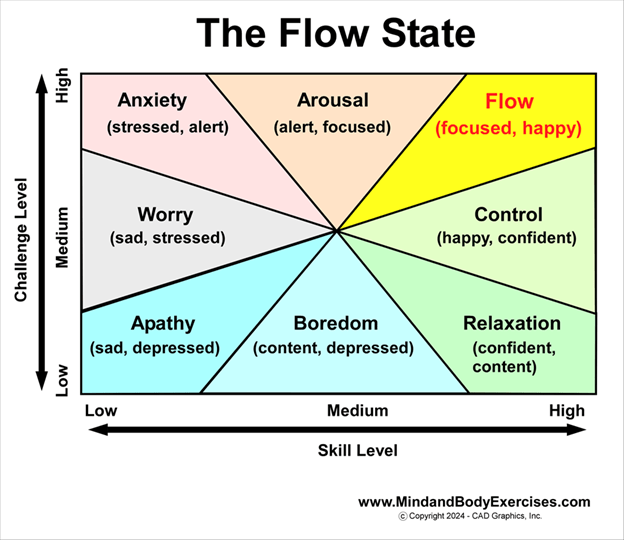

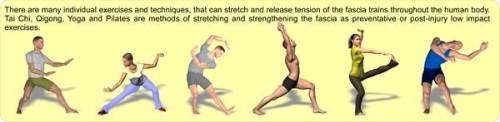

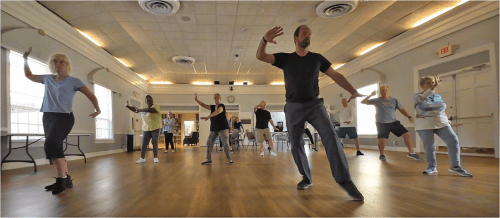

In integrating this into holistic and/or martial arts philosophy (Tai Chi, Bagua, Qigong, etc.), the training forms, the repetitive drills, the internal alignments, the meditations, the stance work, all of these provide the “pressure chamber” in which subtle weaknesses (postural misalignment, mental chatter, emotional reactivity) are exposed. We can “take apart” our default responses by slow mindful repetition, by breaking and rebuilding the body-mind link. Over time we can reassemble into someone who moves from center, aligned in structure, calm in mind, responsive in body, as the sword forged, the diamond formed. That formation is not only for combat or technique but for human character: greater clarity, sharper discernment, stronger resilience, deeper compassion.

Finally, the metaphors of glass and sword and diamond remind us that refinement is not about making something brittle or inflexible. A diamond is hard but also rare and valued; tempered glass remains flexible in the sense of resisting sudden break; a well-forged sword has strength but also resilience, edge but also integrity. The cultivated person is not rigid or inflexible, but resilient and discerning; not hardened by bitterness but refined by purpose. True cultivation (in Taoist terms) is returning to one’s original nature of goodness, clarity and unity with the Tao (Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism, 2025). Thus the journey of applying pressure, refining, deconstructing and reconstructing becomes a path to higher humanness.

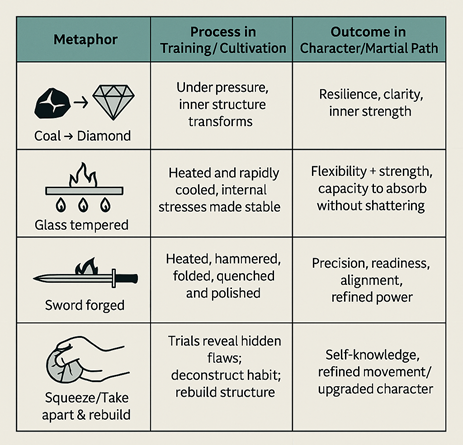

Expanded Insight – Summary Table

| Metaphor | Process in Training / Cultivation | Outcome in Character/Martial Path |

| Coal → Diamond | Under pressure, inner structure transforms | Resilience, clarity, inner strength |

| Glass tempered | Heated and rapidly cooled, internal stresses made stable | Flexibility + strength, capacity to absorb without shattering |

| Sword forged | Heated, hammered, folded, quenched and polished | Precision, readiness, alignment, refined power |

| Squeeze/Take apart & rebuild | Trials reveal hidden flaws; deconstruct habit; rebuild structure | Self-knowledge, refined movement/mind, upgraded character |

- The “squeeze” corresponds to facing real challenge, such as training under fatigue, mental adversity, resisting egoic impulses.

- “Taking apart” corresponds to unlearning: posture, reflexes, mental habits, emotional reactivity.

- “Putting back together” corresponds to rebuilding through alignment, mindful movement, meditative awareness, ethical discipline.

- The end state is not perfection in the sense of rigidity, but refined flexibility, integrated power, clear purpose.

In summary, the metaphors of coal under pressure producing diamond, glass tempered, sword forged, and the squeeze/deconstruction/reconstruction process, are profoundly apt for describing a martial-art and Taoist vision of self-cultivation. They reflect an understanding that becoming a person of refined humanness involves more than mere physical technique: it demands pressure (challenge), refinement (attention, repetition, unlearning), rebuilding (integration of mind/body/spirit), and emergence into a state of character and ability that is both strong and flexible, sharp and compassionate.

In this sense, all of these metaphors of coal, glass, sword, and the squeeze, describe not only refinement but transmutation: the intentional evolution of the inner substance of the self through sustained practice, ethical tempering, and conscious transformation. In the Taoist tradition of internal alchemy, we see this very schema: transforming the body-mind through disciplined practice until one returns to original nature or emerges into a new, refined state (Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism, 2025; Komjathy & The Yuen Yuen Institute, 2008). These metaphors explicitly embody the concept of the Warrior, Scholar & Sage, as principles that connect physical technique with inner alchemical transformation, so that practitioners understand that the pressure in training is not incidental, but rather it is intrinsic to the forging and cultivation of their character.

References:

Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism. (2025). Taoism: Cultivating Body, Mind and Spirit. https://www.taoist.org/taoism-cultivating-body-mind-spirit/ (Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism)

Kohn, L. (2009). Internal Alchemy: Self, Society, and the Quest for Immortality. Three Pines Press.

Komjathy, L. & The Yuen Yuen Institute. (2008). Handbooks for Daoist practice [Book]. The Yuen Yuen Institute. https://ia803408.us.archive.org/3/items/daoist-scriptures-collection-english-translations/Handbooks%20for%20Daoist%20Practice%20-%20%281%29%20Introduction%20-%20Louis%20Komjathy.pdf

Needham, J. (1983). Science and Civilisation in China: Vol. 5. Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part V: Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Physiological Alchemy. Cambridge University Press.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, September 30). Neidan. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neidan?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, October 11). Wu wei. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_wei?utm_source=chatgpt.com