The Korean phrase Myung Sung literally translates as bright thought or clear reflection. In modern Korean, it is also the standard term for “meditation.” In English, the concept has been presented as Living Meditation, an embodied, everyday mindfulness woven into the fabric of ordinary life.

Although Myung Sung is distinctly Korean in name, its roots are Sino-Korean, derived from the Chinese characters 明 (ming, bright/clear) and 想 (xiang, thought/reflection). Comparable ideas appear across East Asian traditions: in Chinese Taoism, alignment with the Dao emphasizes clarity and flow; In Japanese, Meisō is the most direct equivalent, while Ichigyō Zanmai describes being fully absorbed in a single activity, similar to the idea of “Living Meditation.” Thus, “Living Meditation” is not confined to one culture, it is a shared practice of engaging fully and harmoniously with life.

This article critically examines the guiding principles of Living Meditation (Myung Sung), situating them within Taoist philosophy, Zen practice, and modern mindfulness research.

Taoist and Cultural Foundations of Living Meditation

Taoist philosophy views life as an ongoing process of aligning with the Tao, or the natural order of the universe. The Tao emphasizes balance, spontaneity, and effortless action (wu wei) (Kohn, 2020). In Korea, these ideas merged with Confucian ethics and Buddhist practices, producing unique expressions such as Myung Sung. In Japan, Zen Buddhism developed a parallel emphasis on mindfulness in daily activities, from tea ceremonies to martial arts (Suzuki, 1956).

The literal meaning of Myung Sung being “bright reflection” captures the essence of Taoist and Zen practice: illuminating the mind, clarifying perception, and cultivating awareness moment by moment. By viewing meditation as an active, daily process, Living Meditation stands apart from traditions that encourage withdrawal from worldly concerns. Instead, it insists that clarity, harmony, and enlightenment are found in the midst of life.

Mindfulness and Living Meditation

Western psychology defines mindfulness as “moment-to-moment awareness of one’s experience without judgment” (Kabat-Zinn, 2015, p. 148). Myung Sung aligns with this definition but extends it. Rather than being limited to seated practice, it emphasizes that every action, from working to communicating to parenting, can become an act of mindful clarity.

This mirrors Taoist teaching on yin-yang balance and Zen’s shikan taza (“just sitting”), but it goes further in emphasizing relational legacy. Myung Sung asks not only how one lives in the present, but also what seeds of goodness and compassion one leaves for future generations. This collectivist orientation aligns with East Asian traditions of intergenerational responsibility (Li, 2007).

Developments in mindfulness research indicate that these interventions can be successfully adapted to diverse environments, including schools, workplaces, clinical settings, prisons, and military contexts, confirming their wide applicability in contemporary society (Creswell, 2016).

The Eight Principles of Living Meditation

1. Know Your True Self

Self-awareness is described as the foundation of all growth. To know the “true self” is to recognize both the visible and invisible aspects of being. Taoism encourages similar introspection, while Zen uses the term kenshō (“seeing one’s true nature”) to describe this realization.

2. The True-Right-Correct Method

Decision-making is guided by balancing the true (inner feelings), the right (socially beneficial actions), and the correct (harmonious integration of both). This echoes Taoist ethics of balance and the Confucian Doctrine of the Mean (zhongyong).

3. Stop Being Drunk on Your Own Thoughts

In Korean, the phrase Doe Chi literally means to be “drunk on” something or caught up, clouded, and overly attached to one’s own mental noise. This principle warns against excessive attachment to rigid beliefs. Taoism also cautions against clinging to fixed ideas, while Zen emphasizes detachment from discursive thinking.

4. How Will You Be Remembered?

Legacy is framed as the planting of seeds for future generations. Confucian philosophy similarly stresses filial piety and the continuation of virtue across time.

5. Seek Connectedness and Honor

All beings are interrelated, and honor means living with respect, integrity, and compassion. Taoist cosmology views humans as part of a larger web of qi (vital energy), while Confucian ren emphasizes relational humaneness.

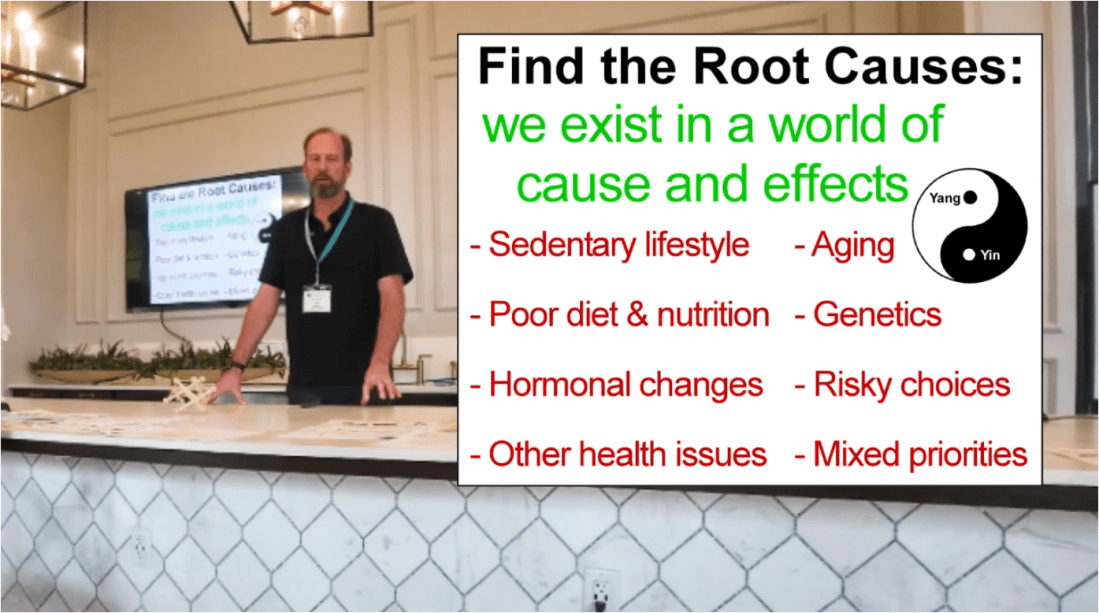

6. Change Your Reality for the Better

Living Meditation insists that inner states shape external realities. Taoist practice of aligning qi with the environment parallels this principle, while modern psychology recognizes the transformative power of reframing thought patterns (Beck, 2011).

7. It Only Takes One Match to Light a Thousand

Small actions produce ripple effects. Taoist yin-yang dynamics and Zen karmic teachings both affirm that even minor choices influence larger outcomes.

8. Be Like Bamboo

Bamboo, strong yet flexible, symbolizes resilience. Taoist writings and Zen poetry both use natural metaphors to highlight adaptability, balance, and endurance.

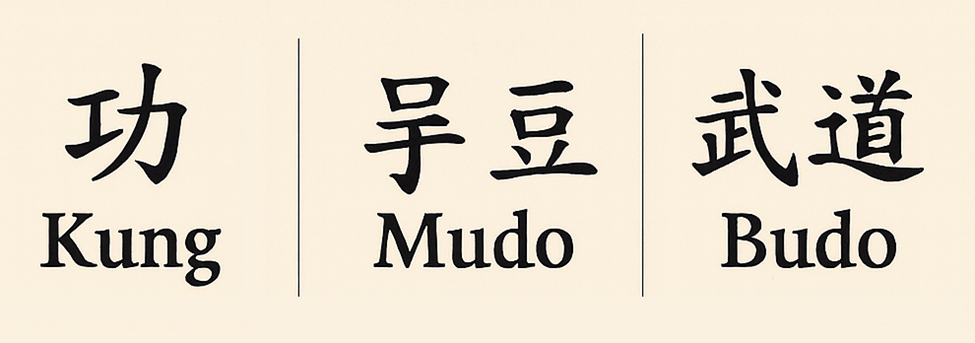

The Three Pillars: Meditation, Medicine, and Movement

Living Meditation is supported by three interconnected practices:

- Meditation – continuous mindfulness integrated into daily activity.

- Medicine – natural remedies and holistic care, paralleling Chinese and Japanese traditional medicine.

- Movement – practices such as Qigong, Tai Chi, or martial arts, uniting body, mind, and spirit.

These three dimensions resemble integrative health frameworks that modern medicine increasingly recognizes (Rakel, 2017).

Conclusion

Though the term Myung Sung originates in Korea and literally means “bright reflection,” its essence transcends culture. Chinese Taoism calls for clarity and balance through the Tao; Japanese Zen offers expressions such as meisō, ichigyō zanmai, and kenshō. English captures it as “Living Meditation,” underscoring its practical, everyday application.

Across languages and traditions, the message is consistent: meditation is not withdrawal from life but illumination within it. By practicing Living Meditation, individuals cultivate clarity, resilience, compassion, and legacy becoming, in essence, living embodiments of bright reflection.

| Language | Term | Literal Meaning | Common Use / Context |

| Korean | Myung Sung | Bright reflection, clear thought | General word for meditation; reframed as “Living Meditation” |

| Chinese | Míng Xiǎng | Bright reflection | Classical and modern meditation term |

| Japanese | Meisō | Closing the eyes and reflecting | General meditation term, closest literal match to Myung Sung |

| Japanese | Ichigyō Zanmai | Samadhi in one activity | Zen concept of mindfulness in everyday action, similar to Living Meditation |

| Japanese | Kenshō | Seeing one’s true nature | Zen awakening experience, parallels “Know Your True Self” |

| English | Living Meditation | Practical mindfulness in daily life | Translation/adaptation of Myung Sung for modern contexts |

References:

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Creswell, J. D. (2016). Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2015). Mindfulness. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1481–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0456-x

Kohn, L. (2020). The Taoist experience: An anthology. SUNY Press. https://archive.org/details/thetaoistexperienceliviakohn

Li, C. (2007). An Introduction to Chinese Philosophy: From Ancient Philosophy to Chinese Buddhism ? by JeeLoo Liu. Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 34(3), 458–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6253.2007.00432.x

Rakel, D. (2017). Integrative Medicine: Fourth Edition. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328497403_Integrative_Medicine_Fourth_Edition

Suzuki, D. T. (1956). Zen Buddhism: Selected writings. Grove Press. https://archive.org/details/zenbuddhismselec00dais