Winter, Immunity, and the Unsustainable Model of Modern Healthcare. Why Lifestyle Medicine Must Become the First Line of Defense

Winter has long been recognized as a season of heightened illness, commonly referred to as “flu season.” This pattern has existed for thousands of years, shaped by environmental conditions, reduced sunlight, behavioral changes, and altered activity patterns. Yet despite humanity’s long-standing awareness of these seasonal rhythms, modern healthcare systems, particularly in the United States, continue to respond with a predominantly pharmaceutical-centered model. Vaccines and medications are promoted as the primary line of defense, while foundational health behaviors such as nutrition, movement, sunlight exposure, sleep, and stress regulation receive comparatively little emphasis.

You can watch my short video on this topic at:

This strategy is proving unsustainable. The United States now faces a continuous decline in both physical and mental health, rising chronic disease burden, escalating healthcare costs, and worsening quality of life indicators. The growing reliance on pharmaceutical intervention without addressing underlying behavioral and environmental contributors has created a reactive, symptom-focused system rather than a proactive, resilience-based model of health. This essay argues that a fundamental reorientation toward lifestyle medicine as the primary foundation of public health is not only logical, but essential for reversing current health trajectories.

The Predictable Nature of Winter Illness

Seasonal illness is not random. Respiratory infections, influenza, and other viral illnesses consistently peak during winter months due to a convergence of physiological, behavioral, and environmental factors. These include increased indoor crowding, reduced physical activity, poorer dietary habits, higher alcohol consumption, disrupted sleep, and reduced exposure to sunlight (Eccles, 2002; Dowell & Ho, 2004).

Human physiology evolved in close relationship with seasonal rhythms. Historically, winter was a period of reduced food availability, lower caloric intake, and continued physical labor. In contrast, modern winter behavior is characterized by caloric excess, sedentary lifestyles, and prolonged indoor confinement, conditions that directly suppress immune function and metabolic health (Booth et al., 2012).

The seasonal rise in illness is therefore not an unavoidable biological fate, but a predictable consequence of modern lifestyle patterns layered onto ancient physiology.

Vitamin D Deficiency: A Global and Seasonal Crisis

One of the most significant contributors to winter immune vulnerability is widespread vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D synthesis is dependent on ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation from sunlight, which is largely absent during winter months in northern latitudes. As a result, deficiency rates increase dramatically during this season.

Globally, over one billion people are estimated to be vitamin D deficient (Holick, 2007). In the United States, approximately 40–60% of adults have insufficient levels during winter months (Forrest & Stuhldreher, 2011). Vitamin D plays a central role in immune regulation, influencing innate immunity, T-cell function, and inflammatory control (Aranow, 2011).

Low vitamin D levels are associated with increased risk of respiratory infections, influenza, autoimmune disease, and poorer outcomes in viral illness (Martineau et al., 2017; Gombart et al., 2020). Yet despite this robust evidence base, vitamin D status is rarely assessed or addressed in routine clinical care.

Physical Inactivity and Immune Suppression

Physical activity is one of the most powerful modulators of immune function. Regular movement enhances immune surveillance, improves lymphatic circulation, reduces chronic inflammation, and improves metabolic health (Nieman & Wentz, 2019).

Conversely, physical inactivity, now widespread in industrialized nations, has been shown to increase susceptibility to infection, worsen vaccine response, and promote chronic low-grade inflammation (Booth et al., 2012; Hamer et al., 2020). Winter months exacerbate sedentary behavior, as colder temperatures and shorter daylight hours reduce outdoor activity.

The modern human body, designed for daily movement, now spends most of its time in chairs, cars, and climate-controlled environments. This mismatch between evolutionary design and modern behavior contributes directly to immune dysfunction and chronic disease.

Ultra-Processed Food and Immune Dysfunction

Diet quality is another central determinant of immune health. Modern winter diets are often dominated by ultra-processed foods high in refined carbohydrates, industrial seed oils, additives, preservatives, and sugar. These foods disrupt gut microbiota, promote insulin resistance, increase systemic inflammation, and impair immune signaling (Monteiro et al., 2018; Zinöcker & Lindseth, 2018).

The gut microbiome plays a critical role in immune regulation, with approximately 70% of immune cells residing in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (Belkaid & Hand, 2014). Diets rich in whole foods, vegetables, fruits, legumes, lean proteins, and healthy fats, support microbial diversity and immune resilience, while ultra-processed foods degrade this vital ecosystem.

The widespread replacement of traditional diets with industrial food products represents one of the most profound biological experiments in human history, and its results are increasingly evident in rising rates of obesity, diabetes, autoimmune disease, depression, and cardiovascular illness.

Mental Health Decline and Immune Consequences

The decline in mental health over recent decades parallels the deterioration of physical health. Rates of anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and suicide have risen sharply in the United States (Twenge et al., 2019; CDC, 2023). Chronic psychological stress suppresses immune function through dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and increased cortisol exposure (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005).

Social isolation, now increasingly common further compounds this effect. Loneliness has been shown to increase inflammatory signaling and reduce antiviral immune responses (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). Winter confinement and digital substitution for human connection intensify this problem.

The modern epidemic of loneliness, combined with chronic stress and digital overexposure, represents a silent immune suppressant operating year-round.

The Reactive Model of Modern Healthcare

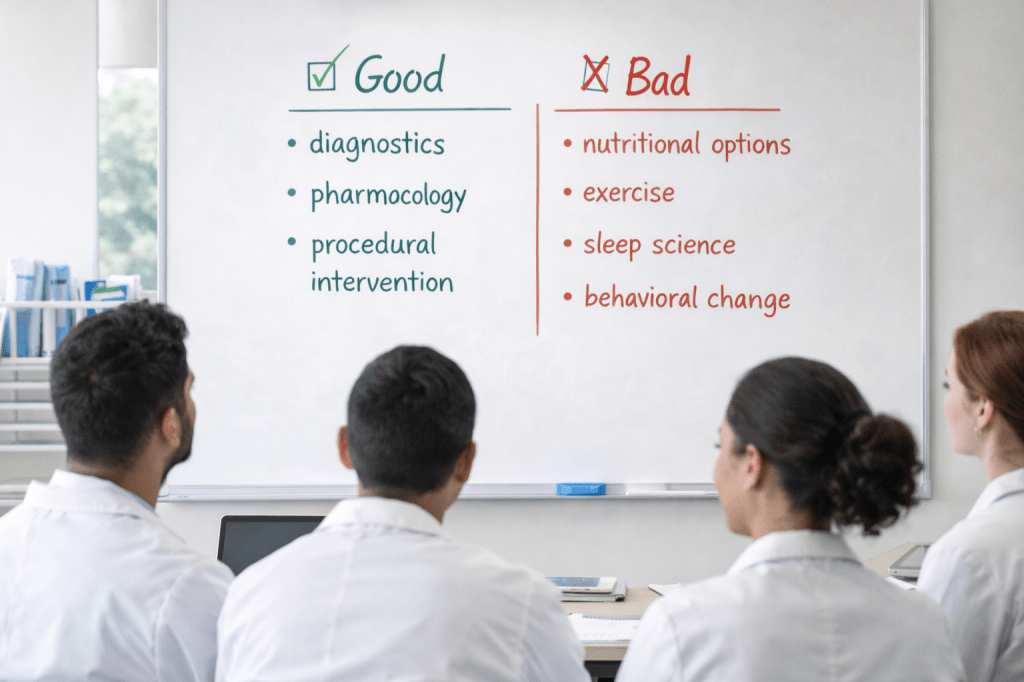

The current healthcare system in the United States is primarily structured around disease management rather than health creation. Physicians receive minimal training in nutrition, exercise physiology, sleep science, or behavioral change counseling (Adams et al., 2010; Devries et al., 2019). As a result, clinical encounters are dominated by diagnostics, pharmacology, and procedural intervention.

This model is highly effective for acute trauma and infectious disease management. However, it is poorly suited for addressing chronic, lifestyle-driven illnesses. The system is financially incentivized to treat disease after it develops rather than prevent it from occurring.

Vaccines and medications are promoted as population-level solutions because they can be standardized, deployed rapidly, and measured easily. Lifestyle change, by contrast, requires time, education, accountability, and cultural transformation.

The result is a healthcare system that waits for illness to emerge rather than building resilient physiology in advance.

The Unsustainable Trajectory of U.S. Health

Despite spending more on healthcare than any nation in the world, the United States ranks poorly in life expectancy, chronic disease burden, and quality-of-life metrics (Tikkanen & Abrams, 2020). Obesity rates exceed 40%, diabetes affects over 11% of adults, and cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death (CDC, 2023).

Mental health outcomes have deteriorated alongside physical health. The pharmaceutical expansion has not reversed these trends. Instead, the nation now consumes more prescription medications per capita than any other country while continuing to grow sicker.

This trajectory is not sustainable economically, biologically, or socially.

Reclaiming the Logical Hierarchy of Health

Human physiology evolved in an environment defined by:

- Daily physical labor

- Seasonal sunlight exposure

- Whole-food nutrition

- Natural circadian rhythms

- Social cooperation

- Environmental challenge

Modern life has inverted these conditions. The logical hierarchy of health must be restored:

- Nutrition quality

- Physical movement

- Sleep hygiene

- Sunlight exposure

- Stress regulation

- Social connection

- Medical intervention when necessary

Pharmaceuticals should function as supportive tools—not the foundation of human health.

This integrative model does not reject medicine. It restores medicine to its proper role.

Winter illness is not merely a seasonal inconvenience, it is a symptom of a broader systemic failure to align modern life with human biology. The current healthcare model, built on pharmaceutical intervention rather than physiological resilience, is incapable of reversing the ongoing decline in physical and mental health.

Encouraging better nutrition, more movement, adequate sunlight exposure, sufficient sleep, stress regulation, and social connection is not alternative medicine. It is foundational medicine.

Without a return to these biological essentials, no number of pharmaceuticals will reverse the trajectory of modern disease. The future of healthcare must shift from managing illness to cultivating health. Only then can winter become a season of resilience rather than vulnerability.

References:

Adams, K. M., Kohlmeier, M., Powell, M., & Zeisel, S. H. (2010). Nutrition in medicine: nutrition education for medical students and residents. Nutrition in clinical practice : official publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 25(5), 471–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533610379606

Aranow, C. (2011). Vitamin D and the immune system. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 59(6), 881–886. https://doi.org/10.2310/JIM.0b013e31821b8755

Belkaid, Y., & Hand, T. W. (2014). Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell, 157(1), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011

Booth, F. W., Roberts, C. K., & Laye, M. J. (2012). Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Comprehensive Physiology, 2(2), 1143–1211. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c110025

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Chronic disease indicators and mental health statistics. https://www.cdc.gov

Devries, S., Dalen, J. E., Eisenberg, D. M., Maizes, V., Ornish, D., Prasad, A., Sierpina, V., Weil, A. T., & Willett, W. (2014). A deficiency of nutrition education in medical training. The American journal of medicine, 127(9), 804–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.003

Dowell, S. F., & Ho, M. S. (2004). Seasonality of infectious diseases and severe acute respiratory syndrome—What we don’t know can hurt us. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 4(11), 704–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01177-6

Eccles, R. (2002). An explanation for the seasonality of acute upper respiratory tract viral infections. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 122(2), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480252814207

Forrest, K. Y. Z., & Stuhldreher, W. L. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of vitamin D deficiency in US adults. Nutrition Research, 31(1), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2010.12.001

Glaser, R., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2005). Stress-induced immune dysfunction. Nature Reviews Immunology, 5(3), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1571

Gombart, A. F., Pierre, A., & Maggini, S. (2020). A review of micronutrients and the immune system. Nutrients, 12(1), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010236

Hamer, M., Kivimäki, M., Gale, C. R., & Batty, G. D. (2020). Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: A community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 87, 184–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.059

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Holick, M. F. (2007). Vitamin D deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(3), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra070553

Martineau, A. R., et al. (2017). Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections. BMJ, 356, i6583. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6583

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Moubarac, J. C., Levy, R. B., Louzada, M. L. C., & Jaime, P. C. (2018, January 1). The un Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutrition. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000234

Nieman, D. C., & Wentz, L. M. (2019). The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. Journal of sport and health science, 8(3), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2018.09.009

Tikkanen, R., Abrams, M. K., & The Commonwealth Fund. (2020). U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2019: Higher Spending, Worse Outcomes? In Data Brief. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/Tikkanen_US_hlt_care_global_perspective_2019_OECD_db_v2.pdf

Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E., & Binau, S. G. (2019). Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. Journal of abnormal psychology, 128(3), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000410

Zinöcker, M. K., & Lindseth, I. A. (2018). The Western Diet-Microbiome-Host Interaction and Its Role in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients, 10(3), 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10030365