Now in my sixties, I find myself reflecting on observations that began much earlier in life. Since my teenage years, I have paid close attention to how people behave, how they relate to themselves, and how they interact with others. Over time, certain patterns become difficult to ignore. Pain and suffering, both physical and psychological, are not rare events that suddenly appear in old age. They are present throughout life. I witnessed them early on among relatives, friends, and associates struggling with health issues, emotional burdens, addiction, isolation, and loss.

What strikes me most now is that, as I enter what society often calls the “golden years,” I see many of the very same issues playing out again. They are now appearing not only in those around me, but also within my own body, my own relationships, and my own reflections. Aging does not introduce suffering so much as it reveals what has been quietly accumulating all along.

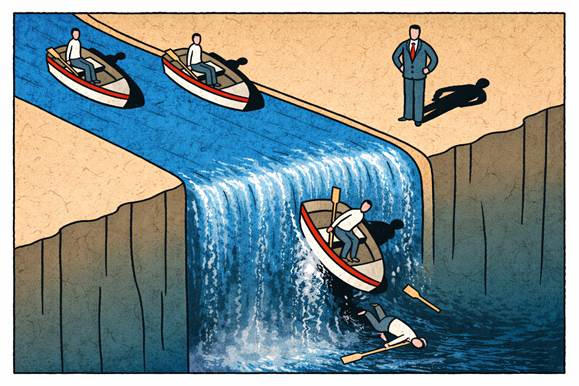

A metaphor that often comes to mind is that of individual boats floating on a river. Each of us is in our own vessel, shaped by our experiences, injuries, beliefs, habits, and fears. And yet we are all on the same river. We know where it leads. The waterfall at the end is not a secret. Mortality is not the surprise. What is surprising is how passively many of us drift toward it, aware of the direction, yet doing little to slow, redirect, or meaningfully engage with the journey itself.

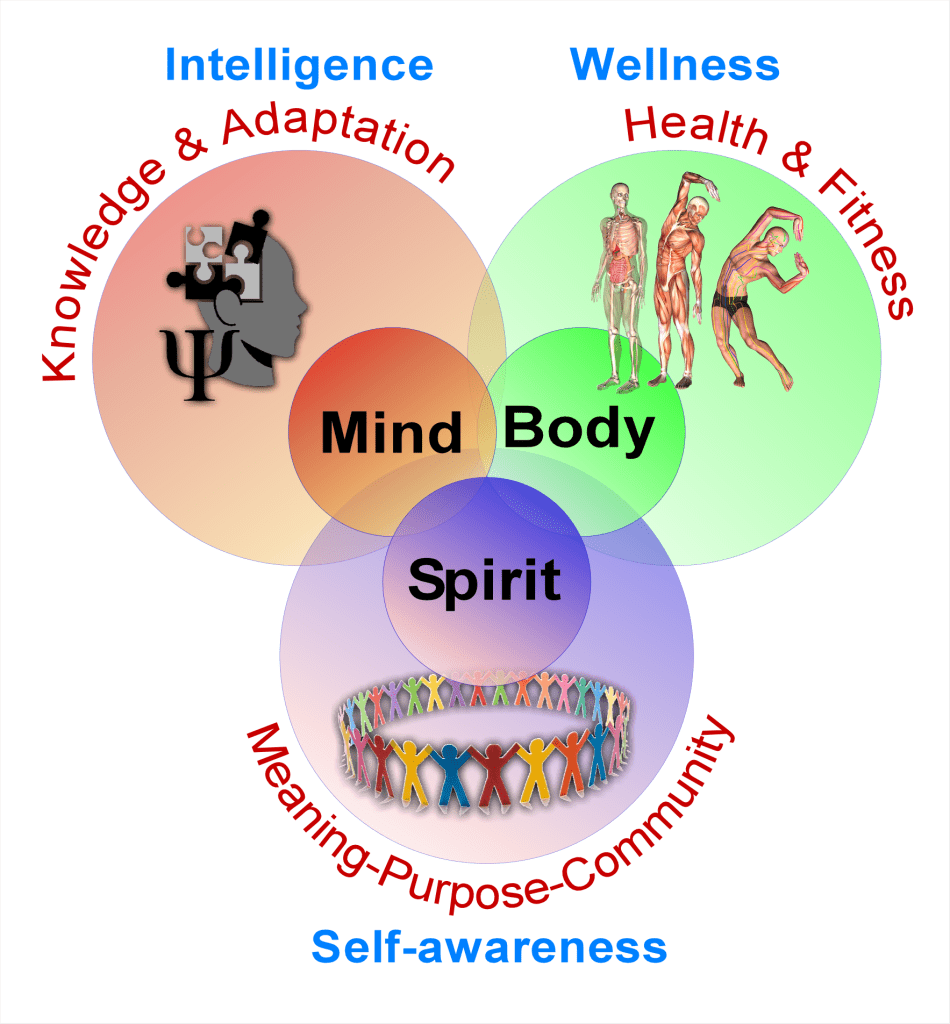

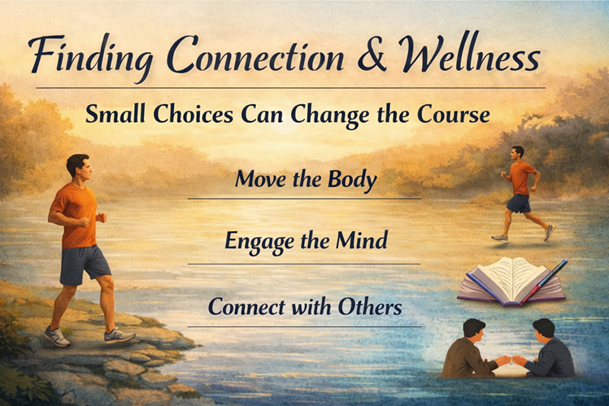

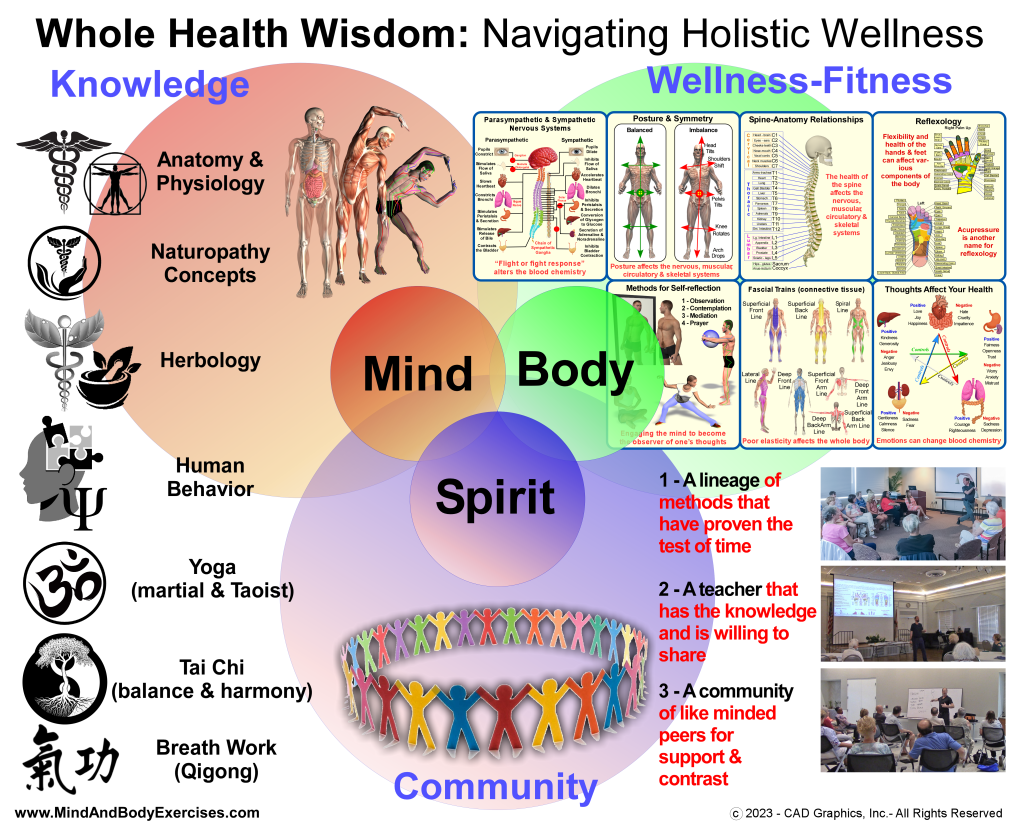

Through decades of study and practice in martial arts, fitness, wellness, and character development, I have seen that much physical pain and mental suffering are not inevitable in the way we often assume. Aging brings change, yes, but deterioration is frequently accelerated by inactivity, isolation, and disengagement. This is where frustration sometimes arises for me. Not because people suffer, but because so many appear unwilling or unable to consider ways of reducing that suffering, even when those ways are accessible and humane.

To engage in practices that promote health, connection, or growth quietly implies that something can be done. Psychological research helps explain why this implication can feel empowering to some and threatening to others. Self-efficacy theory emphasizes the importance of a person’s belief in their ability to influence outcomes through their own actions (Bandura, 1997). When individuals no longer believe that their efforts will make a difference, withdrawal, avoidance, and resignation become understandable responses. From this perspective, resistance to change is not stubbornness or apathy, but a protective response to the fear that trying will only confirm one’s limitations.

This resistance is rarely about a dislike of movement, wellness, or community. More often, it reflects years of diminished confidence, repeated disappointment, or environments that subtly reinforce helplessness. When effort feels futile, suffering becomes something to endure rather than address. Familiar discomfort can begin to feel safer than uncertain improvement.

At the same time, I recognize a tension within myself. When I speak openly about movement, connection, and intentional living, I worry about coming across as preachy, mystical, or overly insistent. I am not a pastor. I am not promoting religion, nor am I suggesting that people join a cult or subscribe to a belief system. I am not even saying that everyone should practice tai chi, qigong, or martial arts. When I refrain from speaking, however, I feel that I am withholding something valuable. I feel that I am not fully honoring the experiences, insights, and responsibilities that come with a lifetime of observation and practice.

This tension is not about convincing or converting others. It is about witnessing. With time, some people naturally step into the role of observer, elder, or quiet guide. Not because they have all the answers, but because they have watched patterns repeat long enough to recognize their consequences. The challenge is learning how to share those observations without turning them into judgements or prescriptions.

One thing I have come to believe deeply is that human beings are not meant to regulate, heal, or make meaning entirely on their own. Loneliness is not simply an emotional state. It is a physiological stressor that affects mood, immune function, and overall health. Prolonged inactivity is not merely a lack of motivation. It contributes to neurological, metabolic, and emotional decline. These are not moral failings. They are relational failures, often reinforced by cultural norms that normalize isolation and passivity, especially in later life.

As people grow older, many intuitively sense the importance of connection, yet they often seek it in indirect or diluted ways. Simply getting out of the house becomes a strategy in itself. Some look for brief interactions at grocery stores, shopping malls, parks, or other public places. Others join social gatherings at churches, recreation centers, or community programs, playing chess, cards, or other games. Many find comfort and companionship in caring for pets, which offer unconditional presence and emotional soothing. These choices are understandable, and they can provide genuine relief from isolation.

However, an important question remains. While these activities offer contact, do they consistently provide the depth of connection and sense of purpose that many people seek as they age? Casual interactions, routine social exposure, or even well-intentioned group activities can still leave an underlying sense of emptiness if they lack shared meaning, mutual growth, or authentic engagement. Being around people is not the same as being with people in a way that nourishes identity, contribution, and belonging.

From a psychological perspective, this distinction matters. Self-determination theory emphasizes that relatedness is not simply about proximity to others, but about experiencing connection that feels mutual, valued, and purposeful (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Likewise, self-efficacy is strengthened not merely through activity, but through participation that allows individuals to feel useful, capable, and seen (Bandura, 1997). Without these elements, social contact can become another form of distraction rather than a source of restoration.

Meaningful connection often emerges where people share interests, challenges, values, or practices that invite participation rather than passive attendance. Whether through movement, learning, service, discussion, or creative expression, deeper connection tends to form when individuals feel they are contributing to something larger than themselves, while still being accepted as they are. In this way, connection becomes not just a buffer against loneliness, but a pathway toward purpose, resilience, and continued growth later in life.

Self-determination theory offers further insight into this pattern by identifying three basic psychological needs that support motivation and well-being: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2000). When people feel they have little choice over their circumstances, when they no longer feel capable in their bodies or minds, and when meaningful social connection fades, motivation naturally erodes. In such conditions, disengagement is not a character flaw. It is an adaptive response to unmet psychological needs.

I see far too many people sitting alone in front of their televisions, day after day, in physical pain from lack of movement and mental suffering from loneliness. Many of them do not describe themselves as lonely. They describe themselves as introverted, tired, bored, anxious, or resigned. Yet beneath these labels is often a quiet grief and a sense of disconnection that no amount of passive entertainment can resolve.

Life is remarkably short. This truth is easy to intellectualize and difficult to feel until much later than we would like. By the time many people recognize the cost of years spent disengaged, rebuilding strength, relationships, and purpose, it all feels overwhelming. And so, the river carries them onward.

Despite our separate boats, we are not truly alone on this river. We move together, influenced by the same currents of aging, cultural distraction, and social fragmentation. This is why individual solutions, while important, are not sufficient on their own. Exercise matters, but so does shared experience. Reflection matters, but so does conversation. Discipline matters, but so does belonging. Environments that emphasize choice, encouragement, and shared participation help restore both self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation by allowing people to experience small successes within supportive social contexts (Bandura, 1997; Deci & Ryan, 2000).

When I speak about wellness, connection, and engagement, I try to do so from observation rather than instruction. I speak from my own struggles, not from a place of authority. I talk about what has helped me manage pain, stress, and meaning, rather than what others should do. I ask questions instead of offering conclusions. I trust that those who are ready will hear what resonates and leave the rest.

I have also come to accept a sobering but liberating truth. Not everyone wants to reduce their suffering. And that is not something I can change. But those who do want to suffer less are often quietly searching for examples, not sermons. They are looking for people who embody coherence, engagement, and a willingness to remain active in life, physically and relationally.

Perhaps the most honest role I can play is not that of teacher or promoter, but of a participant. Someone who keeps paddling, not frantically, but deliberately. Someone who remains available, curious, and open to connection. Someone who extends invitations rather than demands. Whether that invitation takes the form of a class, a walk, a conversation, or a shared interest matters less than the spirit in which it is offered.

If tai chi or qigong resonates, wonderful. If not, there are countless other ways to engage. Art, music, volunteering, discussion groups, gardening, learning, mentoring, movement of any kind. What matters is not the activity itself, but the willingness to participate in life rather than observe it from the sidelines.

We are all on the same river. The current is real. The waterfall is inevitable. But how we travel, whom we travel with, and whether we choose to paddle at all remain within our influence. If sharing that perspective helps even a few people lift their eyes from the screen, move their bodies, or reach out to another human being, then speaking is not preaching. It is simply responding, honestly, to what a lifetime of observation has revealed.

As we age, the question often shifts from how to stay occupied to how to stay meaningfully engaged, with ourselves, with others, and with life itself.

If these reflections resonate with you, you are not alone. Meaningful connection often begins simply by reaching out. I welcome conversations about creating small, supportive gatherings, whether through discussion, movement, shared practice, or reflection, that explore mind, body, and consciousness as integrated aspects of human life. Sometimes the most important step is just finding others willing to paddle alongside us.

References:

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman and Company.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01