Understanding Why the Human Prefrontal Cortex Matures Late

One of the most profound discoveries in neuroscience over the last several decades is that the human brain does not fully mature until well into the mid-twenties. While physical growth often plateaus by late adolescence, cognitive and emotional maturity continue to evolve long afterward. This discrepancy between physical and neural development is primarily due to the slow maturation of the prefrontal cortex, the region responsible for executive functions such as decision-making, impulse control, foresight, and moral reasoning. Understanding this process not only explains the often turbulent behavior of adolescents and young adults but also highlights how life experiences, education, and mindfulness practices can support optimal brain development.

Neurological Foundations of Brain Maturation

During early childhood, the human brain undergoes explosive growth in both neural density and connectivity. However, the adolescent and early adult years are marked by a different kind of neurological transformation, one of refinement rather than expansion. The brain’s gray matter, which is abundant in synaptic connections, peaks in volume during adolescence before undergoing a process called synaptic pruning. This selective elimination of unused connections allows for greater efficiency and specialization within neural networks (Giedd et al., 2012). Simultaneously, myelination, the insulation of neural pathways with fatty sheaths that enhance signal transmission, continues to progress through the frontal lobes well into the mid-twenties (Paus et al., 2008).

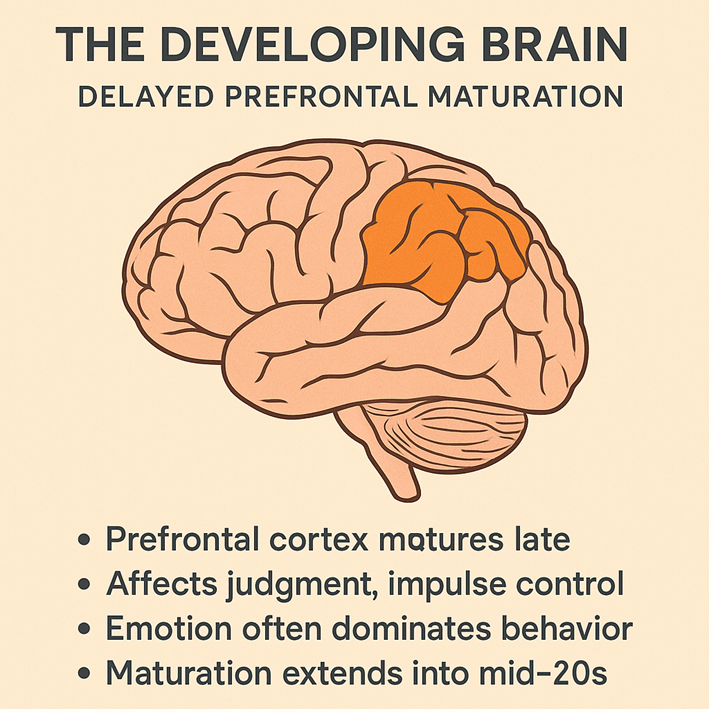

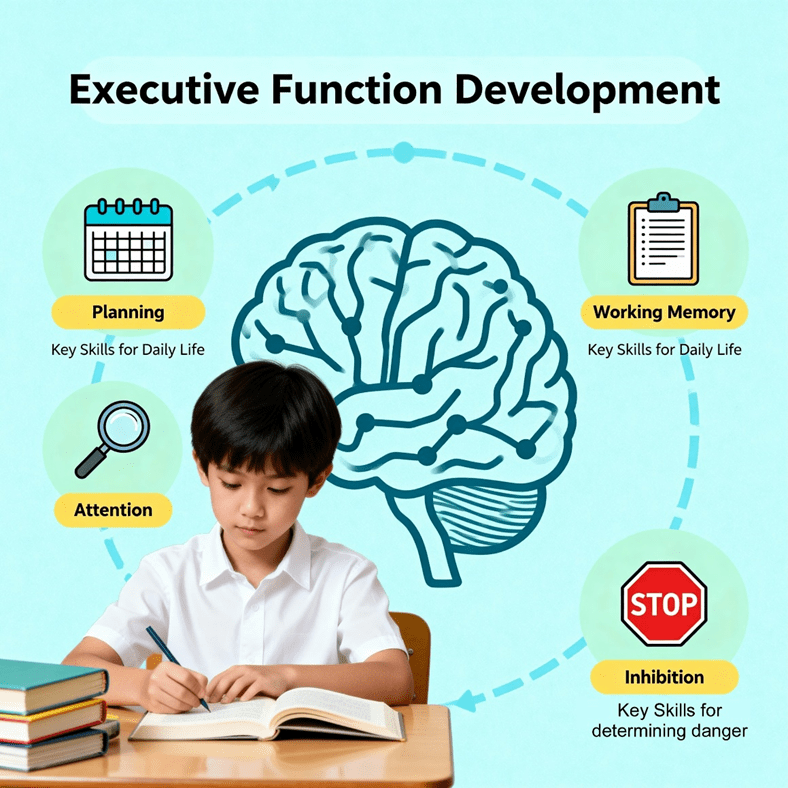

The prefrontal cortex, located just behind the forehead, is the last major brain region to complete these processes. It orchestrates what psychologists call executive functions: planning, organizing, prioritizing, regulating emotions, and exercising self-control. The delayed maturation of this region explains why adolescents and even young adults often display risk-taking behavior, heightened emotionality, and difficulty predicting the long-term consequences of their actions (Casey et al., 2008). In a sense, the “hardware” for rational decision-making exists, but the “software” or the refined connections and pathways that support mature judgment, is still under construction.

Emotional Regulation and Risk Behavior

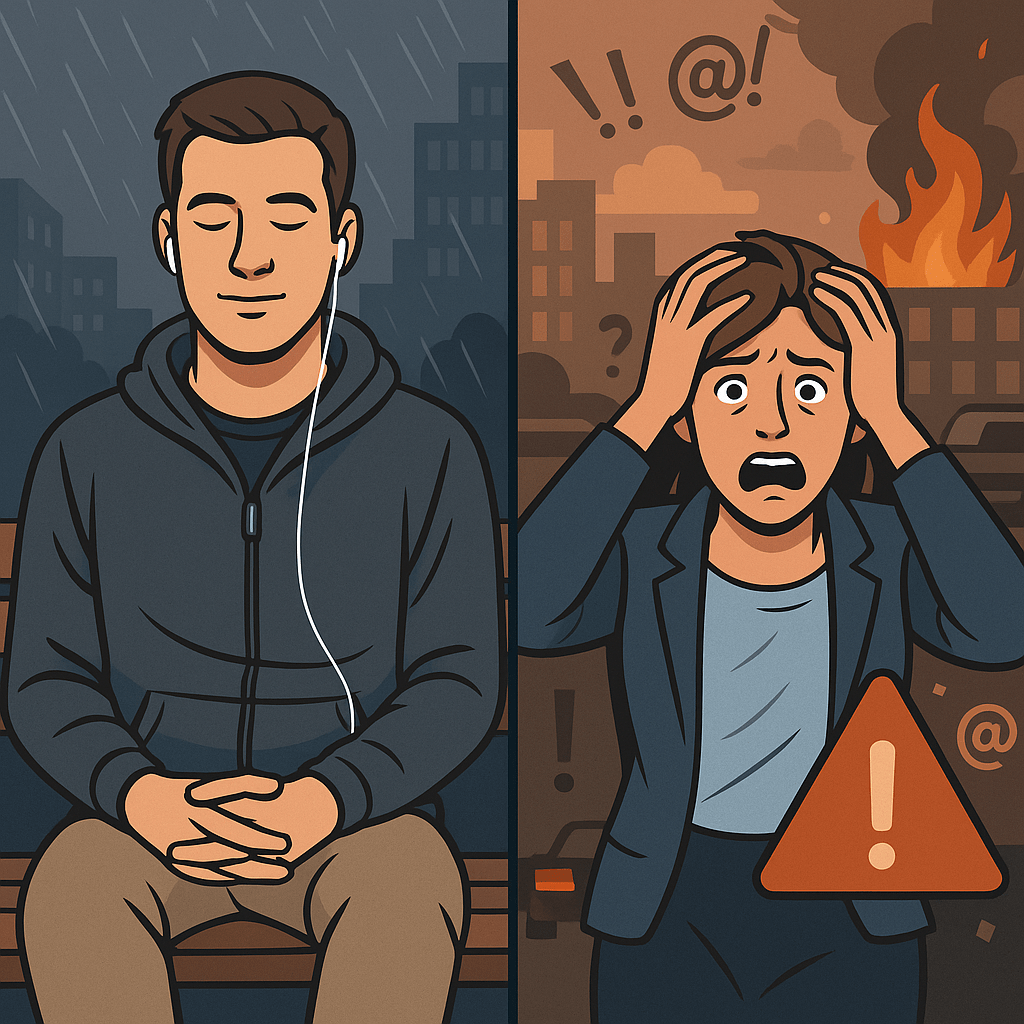

Because the prefrontal cortex matures later than the limbic system (the brain’s emotional center) there is often a developmental mismatch during adolescence. The limbic system, including structures such as the amygdala and nucleus accumbens, becomes highly active and sensitive to reward, novelty, and social approval during the teenage years (Steinberg, 2010). This imbalance leads to emotional intensity and impulsiveness that can overshadow rational thought. Consequently, young people may engage in high-risk behaviors, from reckless driving to substance use, not necessarily because they lack intelligence, but because their cognitive control systems are still evolving.

Hormonal surges during puberty further amplify emotional reactivity, creating a neural environment that prioritizes sensation and social belonging over long-term reasoning (Somerville et al., 2010). While this can lead to errors in judgment, it also fuels exploration, learning, and creativity, all essential components of human development. In this sense, adolescence is not a flaw in design but an adaptive phase that prepares individuals for independence, innovation, and identity formation.

The Role of Experience and Neuroplasticity

The extended development of the prefrontal cortex offers a unique evolutionary advantage: a prolonged window of neuroplasticity. This means that the brain remains malleable and highly responsive to environmental influences throughout the teens and early adulthood. Experiences such as education, social interaction, mentorship, and even adversity all sculpt the brain’s architecture through repeated patterns of thought and behavior (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006). Positive experiences like supportive relationships, mindfulness training, or structured skill development, strengthen neural circuits associated with resilience, empathy, and foresight.

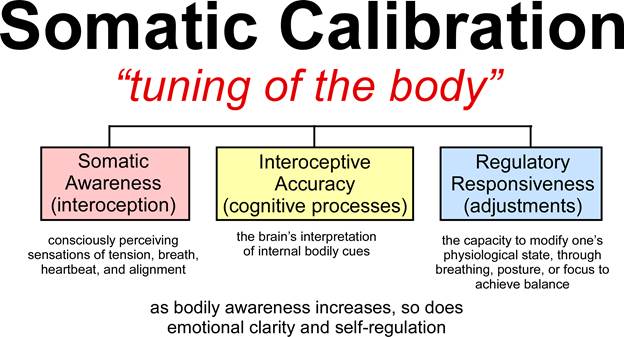

Conversely, chronic stress, trauma, or exposure to substance abuse during this sensitive period can disrupt prefrontal development and lead to long-term difficulties in emotional regulation and decision-making (Luna et al., 2015). This highlights the importance of nurturing environments, holistic education, and practices that promote self-regulation and body awareness during the formative years of brain development.

Enhancing Prefrontal Development Through Mind-Body Practices

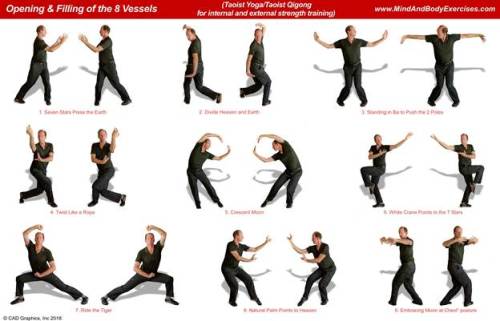

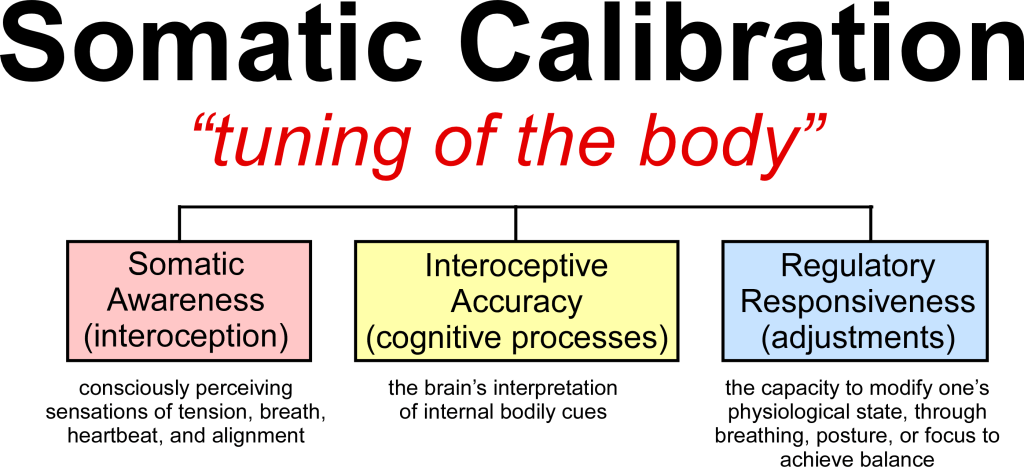

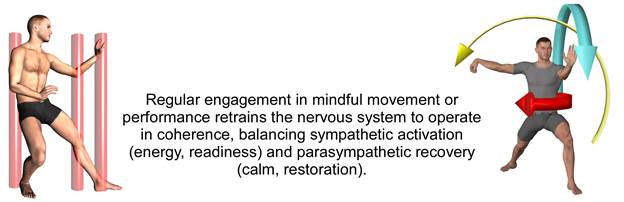

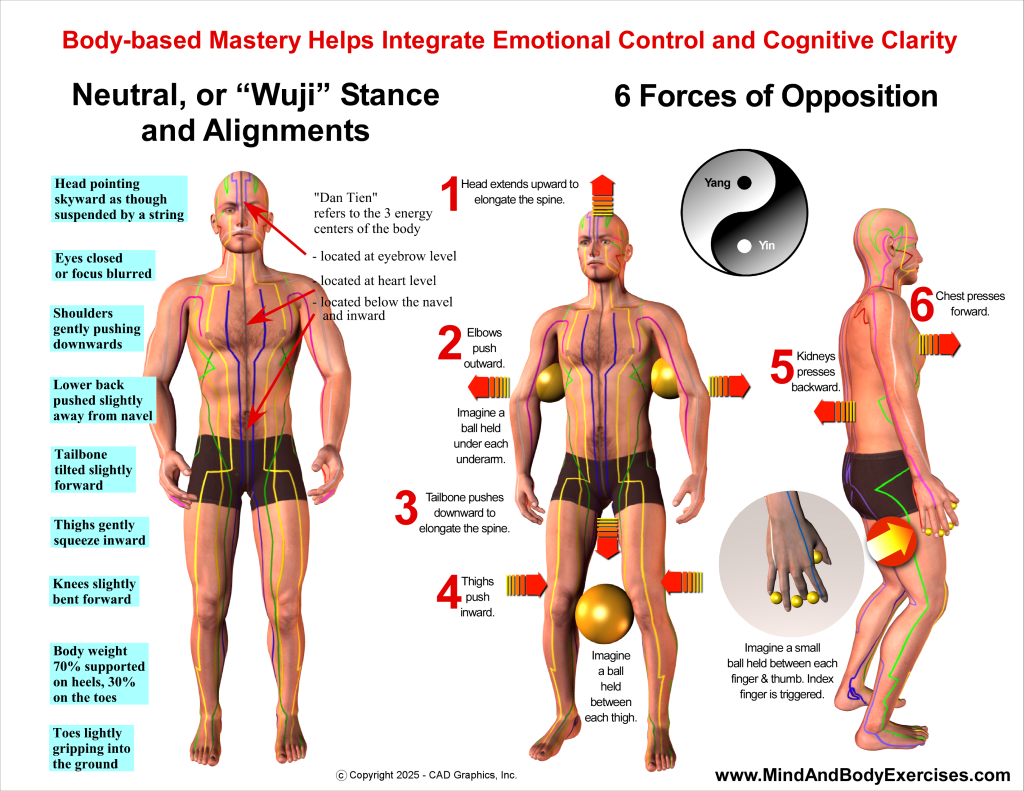

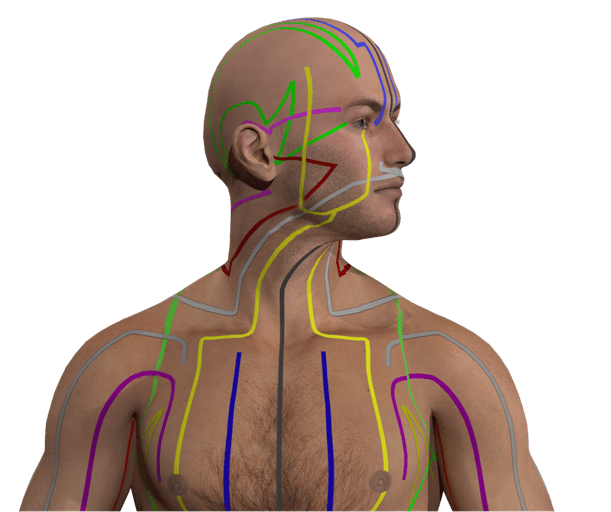

Mind-body disciplines such as yoga, Qigong, Tai Chi, and Bagua Zhang provide valuable pathways to enhance prefrontal development by integrating attention, movement, and emotional regulation. These practices require individuals to cultivate mindfulness, balance, and fine motor control, all of which engage the same neural circuits responsible for executive functioning. Studies have shown that consistent engagement in mindfulness and meditative movement practices can increase cortical thickness and functional connectivity in the prefrontal cortex, leading to improvements in attention, emotional balance, and self-awareness (Tang et al., 2015).

Furthermore, activities that require coordinated, deliberate movement such as martial arts, dance, or even playing a musical instrument, stimulate both hemispheres of the brain and reinforce the mind-body connection. These practices can effectively “train” the prefrontal cortex, helping individuals refine focus, control impulses, and manage stress more effectively. Thus, while biology sets the stage for brain maturation, experience and intentional practice determine the quality of that development.

Implications for Lifelong Growth

Recognizing that the brain continues to mature into the mid-twenties carries significant implications for education, parenting, and social policy. It suggests that late adolescence and early adulthood should not be viewed as the endpoint of development but rather as a critical phase of refinement and responsibility-building. Encouraging environments that promote autonomy, reflection, and self-regulation can help young adults transition more smoothly into mature, balanced individuals.

From a holistic perspective, the developing prefrontal cortex reflects a broader principle of human growth: maturity is not merely a biological milestone but a process of integration of body, mind, and spirit. The capacity for foresight, empathy, and moral reasoning emerges not only through neural wiring but through conscious cultivation. Just as physical training strengthens the body, mindful discipline strengthens the brain, allowing individuals to live with greater purpose, clarity, and wisdom.

References:

Blakemore, S.-J., & Choudhury, S. (2006). Development of the adolescent brain: Implications for executive function and social cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3–4), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01611.x

Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., & Hare, T. A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.010

Giedd, J. N., Raznahan, A., Mills, K. L., & Lenroot, R. K. (2012). Review: magnetic resonance imaging of male/female differences in human adolescent brain anatomy. Biology of Sex Differences, 3(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/2042-6410-3-19

Luna, B., Marek, S., Larsen, B., Tervo-Clemmens, B., & Chahal, R. (2015). An integrative model of the maturation of cognitive control. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38, 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-034054

Paus, T., Keshavan, M., & Giedd, J. N. (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(12), 947–957. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2513

Somerville, L. H., Jones, R. M., & Casey, B. J. (2010). A time of change: Behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.07.003

Steinberg, L. (2010). A dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Psychobiology, 52(3), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20445

Tang, Y.-Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916