Introducing a new book by Jim Moltzan

At its heart, The Path of Integrity is both a philosophical treatise and a psychological guide. A rare combination that bridges ancient wisdom traditions with contemporary understandings of human growth, resilience, and meaning-making.

From a psychological perspective, the manuscript reflects a humanistic foundation, echoing thinkers like Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow in its focus on authenticity, self-knowledge, and the pursuit of a life aligned with core values. The text moves beyond prescriptive “self-help” to address the deeper internal architecture of the self in the mind, body, spirit, and relational being and how each must be cultivated in balance.

The book also engages with existential psychology, confronting questions of purpose, mortality, and moral responsibility. By drawing parallels between the “Path of Integrity” and the “Way of Dissonance,” it frames life as a series of choices that either bring us into alignment with our highest potential or lead us away from it. This dichotomy functions as a form of cognitive re-framing, helping readers see their daily decisions in a broader, values-driven context.

Importantly, the manuscript explores post-traumatic growth, not as an abstract theory but as a lived reality. It acknowledges that adversity, when met with awareness and intention, can deepen resilience, empathy, and wisdom. This theme is woven throughout personal reflections, martial philosophy, and spiritual principles to create a layered and authentic approach to transformation.

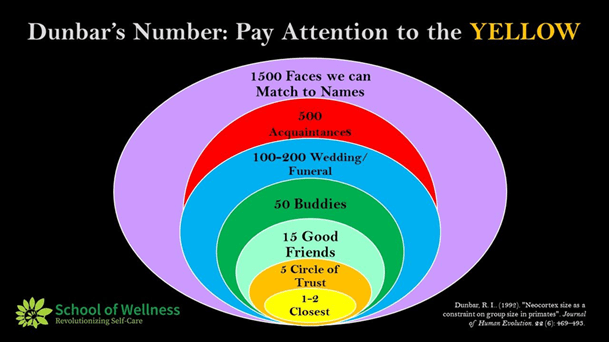

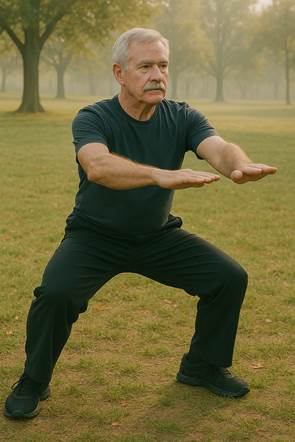

The emphasis on discipline, self-awareness, and service aligns closely with self-determination theory, which holds that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are essential to psychological well-being. The book’s integration of martial arts principles, such as inner guarding, patience, and strategic action, translates these abstract needs into concrete practices.

The style is psycho-educational, offering not only insight but also practical steps, from developing mental clarity and setting energetic boundaries to cultivating stillness as a tool for decision-making. This pedagogical approach makes it equally relevant to martial artists, spiritual seekers, and those navigating the complexities of modern life.

Psychologically, The Path of Integrity stands out because it addresses both the inner terrain (belief systems, emotional regulation, moral reasoning) and the outer application (relationships, teaching, leadership, legacy). This dual focus ensures that readers do not merely reflect but act, integrating new perspectives into daily living.

Ultimately, the book’s psychological message is clear. Integrity is not an abstract ideal. It is a lived state of alignment that requires ongoing attention, honest self-evaluation, and the courage to choose what is right over what is easy. By walking this path, we move beyond survival into a life of grounded purpose, resilience, and contribution.

The Path to Integrity is available at Amazon at: https://a.co/d/bgm7U2t