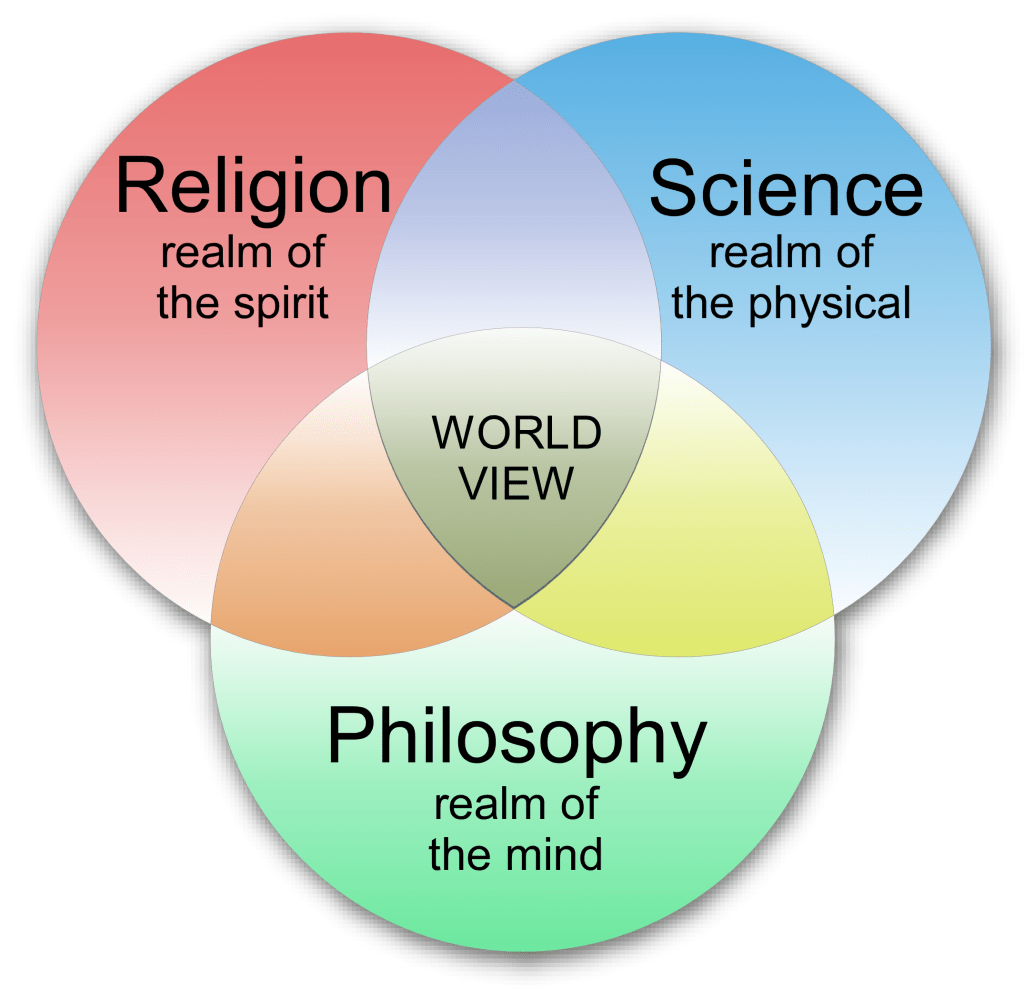

Throughout human history, the quest to understand existence, purpose, and the nature of reality has taken many forms. While these explorations often overlap, they can generally be organized into three interrelated systems of inquiry: faith-based systems, philosophical systems, and scientific systems. Each provides a unique lens through which humanity seeks truth. Faith appeals to divine or spiritual revelation, philosophy relies on reason and reflection, and science depends on observation and empirical validation (Capra, 1975; Wilber, 2000). Together, they represent the triadic foundation of human knowledge and understanding (Russell, 1945; Hawking, 1988). I must comment that some may debate what specific systems fall under what labels.

1. Faith-Based Systems (Religious / Spiritual Traditions)

Faith-based systems are rooted in spiritual conviction and the belief in realities that transcend material experience (Eliade, 1959). They have shaped civilizations, moral codes, and social structures, offering meaning beyond the tangible (Smith, 1991). Whether through monotheism, polytheism, or animism, these systems establish a bridge between the human and the divine (Armstrong, 2006). Faith systems often focus on transformation through belief, ritual, and devotion. They frame life as a sacred journey, interweaving myth, morality, and transcendence into the human story (Otto, 1917/1958; Campbell, 1949).

Major World Religions

- Christianity

- Islam

- Judaism

- Hinduism

- Buddhism

- Sikhism

Indigenous / Ethnic Traditions

- Shinto (Japan)

- Taoism (China)

- Confucianism (often straddles philosophy & faith)

- Native American spiritual traditions

- African traditional religions (e.g., Yoruba, Akan)

- Aboriginal Dreamtime spirituality

Mystical / Esoteric Systems

- Gnosticism

- Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism)

- Sufism (Islamic mysticism)

- Christian Mysticism

- Hermeticism

- Theosophy

- New Age and Neo-Pagan movements

2. Philosophical Systems

Philosophy occupies the middle ground between belief and empirical proof. It explores the “why” and “how” of existence through logic, introspection, and dialogue (Russell, 1945). Philosophical inquiry provides a rational structure for understanding ethics, consciousness, and the principles underlying all experience (Nagel, 1986). Philosophy seeks coherence and meaning through thought rather than faith yet often converges with both spirituality and science in its pursuit of truth. It serves as the bridge between the unseen convictions of religion and the measured observations of science (Wilber, 2000; Capra, 1975).

Classical Philosophy

- Greek: Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism, Epicureanism

- Indian: Vedanta, Samkhya, Nyaya, Yoga, Jain philosophy, Buddhist philosophy

- Chinese: Taoism, Confucianism, Legalism, Mohism

Medieval & Theological Philosophy

- Scholasticism (Thomas Aquinas, Augustine)

- Islamic philosophy (Avicenna, Averroes)

- Jewish philosophy (Maimonides)

Modern Philosophy

- Rationalism (Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz)

- Empiricism (Locke, Berkeley, Hume)

- Idealism (Kant, Hegel)

- Existentialism (Kierkegaard, Sartre)

- Pragmatism (Peirce, James, Dewey)

- Phenomenology (Husserl, Merleau-Ponty)

- Structuralism & Postmodernism (Foucault, Derrida)

Eastern Philosophy

- Taoist metaphysics (Yin–Yang, Wu Wei)

- Zen and Chan Buddhism

- Confucian ethics

- Advaita Vedanta

- Tibetan philosophy (Madhyamaka, Yogācāra)

3. Sciences (Empirical and Theoretical Frameworks)

Science represents the empirical branch of human understanding through testing, measuring, and analyzing the natural world (Popper, 1959). It aims not to interpret meaning but to uncover mechanisms. Rooted in observation and experimentation, scientific disciplines have revolutionized how humanity interacts with the universe (Kuhn, 1962). Through experimentation and evidence, science strives for predictability and control. Yet, even in its rigor, it leaves open the mystery of “why,” which returns the seeker to the realms of philosophy and faith (Einstein, 1930/2005).

Natural Sciences

- Physics

- Chemistry

- Biology

- Astronomy

- Geology

- Ecology

Formal Sciences

- Mathematics

- Logic

- Computer Science

- Statistics

Social Sciences

- Psychology

- Sociology

- Anthropology

- Economics

- Political Science

- Linguistics

Applied Sciences

- Medicine

- Engineering

- Environmental Science

- Neuroscience

- Health Sciences

Emerging / Interdisciplinary Fields

- Cognitive Science

- Systems Theory

- Biophysics

- Artificial Intelligence

- Quantum Information Science

Faith, philosophy, and science form a triad that has guided human civilization toward deeper understanding and evolution. Faith gives meaning to existence, philosophy refines thought and ethics, and science illuminates the mechanics of reality. When harmonized, they represent the full spectrum of human inquiry, in body, mind, and spirit in dynamic equilibrium (Wilber, 2000; Capra, 1996). The synthesis of these systems invites a more holistic comprehension of life itself, reminding us that truth may not lie in one domain alone, but in the dialogue between them (Hawking, 1988; Nasr, 2007).

References:

Armstrong, K. (2006). The great transformation: The beginning of our religious traditions. Knopf. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-07760-000

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. Princeton University Press.

Capra, F. (1975). The Tao of physics. Shambhala. https://archive.org/details/the-tao-of-physics_202504

Capra, F. (1996). The web of life: A new scientific understanding of living systems. Anchor Books. https://archive.org/details/weboflifenewscie00capr

Eliade, M. (1959). The sacred and the profane: The nature of religion. Harcourt Brace. https://archive.org/details/sacredprofanenat00elia

Einstein, A. (2005). Ideas and opinions. Crown. (Original work published 1930)

Hawking, S. (1988). A brief history of time. Bantam Books. https://archive.org/details/briefhistoryofti0000hawk

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Nagel, T. (1986). The view from nowhere. Oxford University Press.

Nasr, S. H. (2007). Religion and the order of nature. Oxford University Press.

Otto, R. (1958). The idea of the holy. Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1917)

Popper, K. R. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. Hutchinson. https://philotextes.info/spip/IMG/pdf/popper-logic-scientific-discovery.pdf

Russell, B. (1945). A history of Western philosophy. Simon & Schuster.

Smith, W. C. (1991). The Meaning and End of Religion. Augsburg Fortress. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1hqdhgt

Wilber, K. (2000). A theory of everything: An integral vision for business, politics, science, and spirituality. Shambhala.