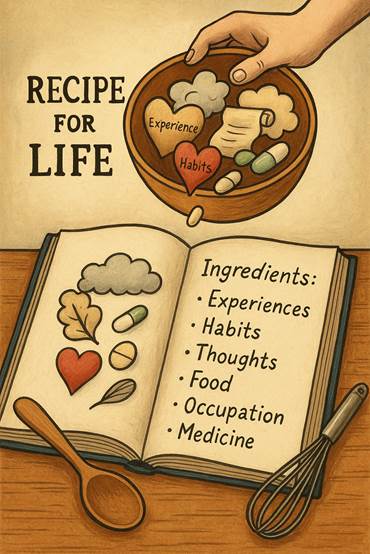

Life, in many ways, is a recipe, as an ever-evolving mixture of choices, habits, relationships, thoughts, and actions. Just as a baker combines flour, sugar, butter, and eggs to produce a cookie, each of us blends experiences, beliefs, and intentions to create our unique outcomes. The image of imperfect cookies illustrates this beautifully: each variation may have too much flour, too little sugar, or overmixing. This reveals how imbalance, excess, or neglect in one area can affect the entire result. Our bodies, minds, and spirits are the ovens in which this recipe bakes, and the quality of what we put in determines what eventually comes out (Seligman, 2011).

The Ingredients of Life

Every life begins with a set of core ingredients: genetic inheritance, environment, education, relationships, nutrition, movement, and purpose. These are our “flour, sugar, and eggs.” Each represents a dimension of well-being that requires mindful measurement.

Flour might symbolize structure and stability, in the routines, responsibilities, and moral foundations that give life its form. Too little structure leads to chaos; too much, and we become rigid, losing spontaneity. Sugar represents pleasure, creativity, and joy, or the sweetness that makes life enjoyable. Depriving ourselves of it can make us bitter, but too much can lead to dependency or self-indulgence. Butter conveys warmth, compassion, and connection; when it is lacking, life becomes dry and crumbly, devoid of emotional cohesion. And eggs, which bind everything together, mirror our inner consciousness, or the vital essence that integrates all experiences into a unified self (Csikszentmihalyi, 2008).

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), health is sustained through balance among elements such as yin and yang or the Five Elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water), which interact like ingredients that must be properly harmonized. When one dominates or depletes another, imbalance arises, similar to a recipe gone wrong (Kaptchuk, 2000). Thus, the ingredients of our lives require ongoing awareness, proportion, and calibration.

Mixing the Ingredients: Balance and Awareness

The act of mixing is where mindfulness enters the recipe. Overmixing the batter of life mirrors overthinking and overcontrolling. These are states that psychologists associate with anxiety and emotional exhaustion (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). Undermixing, conversely, reflects inattention, or a lack of integration between body, mind, and purpose.

In Taoist and holistic thought, balance is not about equal measures but appropriate harmony. The Dao De Jing teaches that “to be too rigid is to break, to be too soft is to lose form” (Lao-Tzu, trans. 2006). Similarly, the recipe for a fulfilling life requires constant recalibration. What nourished us at twenty may not suit us at fifty. The wise “cook” observes the body’s responses, the mind’s tendencies, and the spirit’s needs to adjust accordingly.

Just as mindful eating can transform the physiological experience of food (Bays, 2017), mindful living transforms our relationship to every experience. Awareness becomes the spoon that stirs the bowl; it integrates, blends, and unifies the ingredients into a coherent whole.

Cooking: Transformation Through Heat and Pressure

Once ingredients are combined, heat completes the transformation. In the kitchen, heat activates hidden properties and deepens flavor. In life, heat symbolizes challenge or the friction, stress, and adversity that refine our raw experiences into resilience and wisdom (Frankl, 2006).

The process parallels the Taoist concept of Nei Dan, or inner alchemy, where the practitioner refines the course into the pure through disciplined effort and patience. Similarly, psychologists describe “post-traumatic growth” as the phenomenon in which adversity fosters new strength, perspective, and appreciation (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

A life without heat remains underdeveloped; too much heat, however, can scorch the spirit. Practices such as qigong, tai chi, and meditation serve as thermoregulators for the psyche by balancing sympathetic activation with parasympathetic restoration (Wayne & Kaptchuk, 2008). The goal is not to eliminate stress but to transmute it into transformation, just as dough becomes a golden cookie through precisely applied warmth.

Presentation: The Art of Serving Our Lives

When the cookie emerges from the oven, it reflects every decision made along the way. Its color, texture, and taste are records of process and intention. In human terms, this is the stage of expression and legacy. How our inner work manifests in our actions, relationships, and contributions to others.

Some lives are underbaked, never given enough time or courage to fully develop. Others are overdone and burnt by perfectionism, resentment, or the relentless pursuit of approval. Yet even an imperfect cookie can nourish when crafted with sincerity and love. The key lies in presence: being aware of what we are serving to others and what we are ingesting ourselves, be it thoughts, emotions, or energy.

Adjusting the Recipe

The beauty of the metaphor lies in its invitation to adjust. If life tastes too bitter, add sweetness through gratitude and forgiveness. If it feels too dry, soften it with compassion and rest. If it is heavy, add air through breathwork, laughter, or creativity.

This reflects the principle of iterative self-cultivation: continuous refinement through reflection and adaptation. Neuroscience supports this metaphor as habits and behaviors can be reshaped through neuroplasticity, the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself in response to intentional change (Doidge, 2007). Like a baker improving with each batch, we learn to align ingredients and timing more skillfully over time.

The Final Dish of a Life Well-Lived

The image of the imperfect cookies reminds us that every life is an experiment in balance. Some batches fail; others surprise us. With awareness, patience, and courage, we can create a recipe that embodies authenticity and harmony. The ultimate goal is not perfection but nourishment, for ourselves and those we touch.

In the end, we are both the chef and the dish; the baker and the baked. Every thought, emotion, meal, and relationship becomes part of our flavor profile. By tending carefully to the ingredients of life, we ensure that when our final recipe is complete, it will satisfy not only the hunger for happiness but the deeper longing for meaning and wholeness.

References:

Bays, J. C. (2017). Mindful eating: A guide to rediscovering a healthy and joyful relationship with food (2nd ed.). Shambhala Publications.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper Perennial. https://archive.org/details/flowpsychologyof2008csik

Doidge, N. (2007). The brain that changes itself: Stories of personal triumph from the frontiers of brain science. Viking. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-23192-000

Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press. https://archive.org/details/viktor-emil-frankl-mans-search-for-meaning

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness (2nd ed.). Bantam.

Kaptchuk, T. J. (2000). The web that has no weaver: Understanding Chinese medicine. McGraw-Hill.

Lao-Tzu. (2006). Tao Te Ching (S. Mitchell, Trans.). Harper Perennial. https://ia600209.us.archive.org/16/items/taoteching-Stephen-Mitchell-translation-v9deoq/taoteching-Stephen-Mitchell-translation-v9deoq_text.pdf

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-25554-000

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

Wayne, P. M., & Kaptchuk, T. J. (2008). Challenges inherent to t’ai chi research: part I–t’ai chi as a complex multicomponent intervention. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.), 14(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2007.7170a