In my research of Eastern culture, traditions and even more specifically, martial arts, I have come across some interesting images and photographs warranting further scrutiny and discussion. The mid-20th century image below under discussion captures a seemingly young male in clerical-style robes. At first glance, the formality of the garment, the draped outer layer, and the posture may evoke comparison to Japanese Shinto vestments. However, closer historical and cultural examination reveals that the attire aligns more strongly with Korean Buddhist clerical dress of the period, particularly in the late 1940s. This distinction is significant in interpreting the individual’s identity, role, and cultural context.

This photograph shows mid-20th-century rural Korea, depicting a young Buddhist lay scholar standing within a temple courtyard. The tiled-roof structure in the background reflects traditional hanok temple architecture, while the rough stonework beneath his feet signifies a liminal space between the secular and sacred. The rope strung across the upper frame (cheonjul), likely a ceremonial boundary, demarcates the area used for purification or seasonal rites. Together with the surrounding forested setting, these details express Korea’s enduring Seon (Zen) Buddhist aesthetic in simplicity, natural harmony, and introspection. The young man’s attire is a jangsam robe layered beneath a seungbok and possibly a lightweight durumagi, signifies Buddhist devotion without full ordination, embodying humility and continuity of native spiritual traditions in the years following Japanese occupation (Buswell & Lopez, 2014; Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, 2016; Victoria and Albert Museum, n.d.; Lee, 2007).

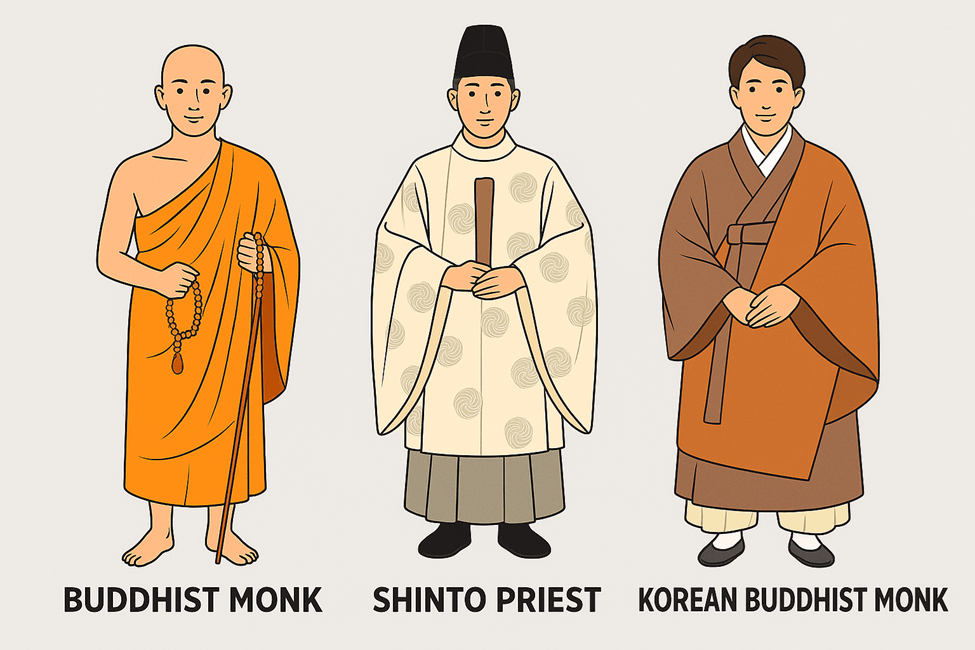

Korean Buddhist Attire: Core Garments

In Korea, Buddhist monks and clerics were distinguished by a layered system of robes that combined both functionality and symbolism (Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, 2016):

- Jangsam: The jangsam was a long-sleeved robe commonly worn by monks in both formal and ritual settings. It served as the foundational clerical garment, similar in form to other East Asian monastic robes but adapted to Korean stylistic preferences. Its ample sleeves and length conveyed dignity and solemnity, reflecting the Buddhist ideal of detachment from worldly vanity (Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, 2016).

- Seungbok: The seungbok was the formal robe, typically heavier in material and reserved for ceremonies. This garment marked elevated ritual occasions and reinforced the clerical role of the wearer. Unlike Japanese Shinto robes (sokutai or jōe), the Korean seungbok emphasized simplicity and austerity rather than ornamental layering (Buswell & Lopez, 2013).

- Durumagi: Over the jangsam or seungbok, Korean monks sometimes wore a durumagi, or an outer coat especially common in colder months or crafted from lightweight ramie during hot summers. The use of ramie, a breathable fabric, reflects both regional textile traditions and the pragmatic adaptation of Buddhist attire to Korea’s humid climate (Lee, 2007; Victoria and Albert Museum, n.d.)

Distinctive Markers of Korean Buddhism

Several key features help distinguish the Korean Buddhist clerical identity in this image from that of a Japanese Shinto priest:

- Garment Structure: Korean monks layered jangsam and seungbok, sometimes with a durumagi, rather than the sokutai and white hakama of Shinto priests.

- Hands and Objects: Korean monks traditionally held the sash (kasa belt) or ribbons of their robes (Buswell & Lopez, 2014). By contrast, Shinto priests often carried a shaku, a flat wooden baton symbolizing authority and ritual meditation (Grapard, 1984).

- Head: A shaved head was a Buddhist marker (Buswell & Lopez, 2014), symbolizing renunciation of worldly attachments. This stands in contrast to Shinto priests, who wore their hair and covered it with the black lacquered eboshi hat, itself a courtly remnant of Japan’s Heian era.

- Color Palette: Korean Buddhist robes were often white, gray, or natural-toned, with colors representing humility and impermanence. In summer, ramie fabric offered a light, breathable weave. This muted aesthetic differs from the brightly layered silks or symbolic colors of Shinto ceremonial vestments.

Historical Context: Korea in the 1940s

The timing of this photograph (circa 1947) is particularly significant. Korea had just emerged from Japanese colonial rule (1910–1945). During the occupation, Japanese cultural and religious symbols, including Shinto shrines, were imposed on the Korean populace. However, Buddhist traditions persisted and adapted.

Thus, while an initial reading of the robes might suggest Japanese Shinto influence, the more accurate interpretation is that these garments represent Korean Buddhist continuity, emphasizing tradition over imposed cultural forms. For a young novice or lay practitioner-scholar, wearing such robes symbolized dedication to the Dharma, education in Buddhist doctrine, and participation in monastic life.

Significance of the Image

This image, therefore, is more than an image of an individual; it embodies a cultural and historical dialogue:

- It reflects Korean Buddhism’s resilience in maintaining distinctive clerical attire despite decades of Japanese cultural hegemony.

- It demonstrates the formalized roles of youth in Buddhist practice, as young novices (sometimes in their teens) trained in monastic settings.

- It highlights the visual markers of identity, robe layering, and sash handling that firmly locate the figure in Korean Buddhist tradition rather than Shinto ritual practice.

The attire in this mid-20th century Korean image should not be mistaken for Japanese Shinto garb. Instead, it exemplifies the distinctive markers of Korean Buddhism: the jangsam, seungbok, and durumagi, worn with simplicity and practicality; the handling of robe sashes. While Shinto may serve as a useful comparative foil, the clothing and cultural cues here strongly support a Buddhist clerical identity in post-liberation Korea (Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, 2016; Victoria and Albert Museum, n.d.).

Three Traditions of East Asian Clerical Attire

| Feature | Shinto Priest (Japan) | General Buddhist Monk (China/India lineage) | Korean Buddhist Monk (Korea) |

| Core Robe | Jōe or sokutai: layered silk robes of court style. | Kasaya: orange/yellow robe draped over one shoulder. | Jangsam: long-sleeved daily/ritual robe. |

| Formal Garment | Sokutai: formal court-style vestment. | Kasaya folded with underrobe for ceremonies. | Seungbok: heavier robe for formal services. |

| Outer Layer | Kariginu or outer mantle. | Optional shoulder robe or upper wrap. | Durumagi: outer coat, ramie in summer. |

| Fabric & Color | Bright silks, symbolic colors. | Cotton/silk, saffron or orange tones. | Ramie/hemp, muted grays or whites. |

| Head | Natural hair with eboshi cap. | Shaved head (Vinaya tradition). | Usually shaved, but lay novices may retain hair. |

| Hands / Object | Shaku (flat baton). | Empty hands or mala beads. | Holds robe sash (kasa belt). |

| Symbolism | Purity, hierarchy, link to imperial rites. | Renunciation, simplicity, discipline. | Humility, devotion, continuity of tradition. |

References:

Buswell, R. E., Lopez, D. S., Ahn, J., Bass, J. W., Chu, W., Goodman, A., Ham, H. S., Kim, S.-U., Lee, S., Pranke, P., Quintman, A., Sparham, G., Stiller, M., & Ziegler, H. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n41q

GRAPARD, A. G. (1992). The Protocol of the Gods: A Study of the Kasuga Cult in Japanese History (1st ed.). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.2392282

Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism. (2016, July 15). Gasa and Jangsam (가사, 장삼). https://jokb.org/bbs/board.php?bo_table=1020&wr_id=12

Lee, P. H. (2007). Sources of Korean Tradition, Vol. 1: From Early Times Through the Sixteenth Century. Columbia University Press.

Victoria and Albert Museum. (n.d.). Hanbok – Traditional Korean Dress (Notes on Durumagi). https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/hanbok-traditional-korean-dress