Physiological, Psychological, and Spiritual Dimensions of a Classical Koan

The aphorism “Death begins in the big toe” is a deceptively simple statement drawn from the long tradition of Chinese medical wisdom and Zen contemplative practice. Like many koans and proverbial sayings from classical East Asian thought, its brevity conceals a depth of layered meaning. At the surface level, it speaks to the observable fact that physiological decline often begins at the extremities. On a subtler level, it gestures toward psychological processes of neglect and dissociation that accompany aging and decay. At its deepest level, the phrase serves as a spiritual teaching about impermanence, awareness, and the cyclic nature of existence.

In Taoist medicine and Chan Buddhist teaching alike, the body is seen as a microcosm of the cosmos, and every small detail reflects the whole. The “big toe” in this aphorism symbolizes more than just anatomy: it is the farthest reach of circulation from the heart, the starting or ending point of many meridians, and the first part of the body to meet the earth with each step. That death might begin there is not a literal prediction but a metaphor for the way life’s endings emerge subtly at the margins before manifesting at the center.

Historical Origins of the Koan

Although the precise origin of the saying is difficult to trace, its spirit can be found in early Chinese medical classics and Zen writings. The Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon), compiled between the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE, repeatedly emphasizes that “illness arises in the extremities before it reaches the organs” and that “to know the distant is to protect the center” (Unschuld, 2003). Similarly, Taoist texts such as the Dao De Jing highlight the principle that great change arises from subtle beginnings: “A tree as great as a man’s embrace springs from a tiny sprout. A journey of a thousand miles begins beneath one’s feet” (Laozi, trans. Addiss & Lombardo, 1993).

In Chan Buddhism, koans often use ordinary body parts as metaphors for the process of awakening or decay. The Tang-era master Yunmen famously remarked, “The toe that touches earth is the whole universe touching earth” (Cleary, 1998), pointing to the subtlety with which the infinite is revealed in the infinitesimal. Over centuries, the saying “death begins in the big toe” entered the shared vocabulary of physicians, monks, and martial artists alike, a succinct reminder that mortality’s first signs are often peripheral and easily overlooked.

Physiological Interpretation: The Body’s Peripheral Messengers

Peripheral Circulation and Aging

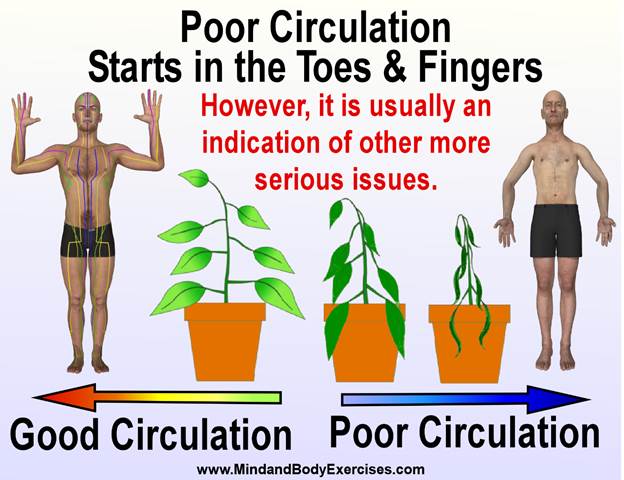

From a biomedical perspective, the big toe is not merely metaphorical. It is literally among the first regions to reveal systemic decline because it sits at the farthest point of the circulatory network. As the heart ages and vascular elasticity decreases, peripheral perfusion diminishes, often manifesting as cold, numb, or discolored toes long before symptoms appear elsewhere (Hamburg & Benjamin, 2009). Peripheral arterial disease, a common condition in older adults, often begins in the feet and toes and is associated with a significant increase in all-cause mortality (Criqui & Aboyans, 2015).

These physiological realities lend empirical support to the ancient observation. If “death” is defined as the progressive failure of the body’s regulatory systems, then it is indeed accurate to say that it begins in the places farthest from the heart and brain. The big toe, as the most distal point of the lower extremities, is the proverbial “canary in the coal mine” for vascular health.

Mobility, Balance, and Longevity

Mobility is another physiological dimension that links the toe to mortality. The toes and particularly the hallux, or great toe, play a crucial role in balance, propulsion, and gait. Degenerative changes, neuropathy, or muscular weakness that impair toe function can reduce walking speed, a biomarker strongly correlated with lifespan (Studenski et al., 2011). Gait speed below 0.8 m/s in older adults is associated with significantly increased risk of disability, hospitalization, and death (Abellan van Kan et al., 2009).

The simple ability to rise from a chair, stand on one’s toes, or walk briskly requires integrated function across multiple physiological systems of the musculoskeletal, nervous, and cardiovascular. Physical decline often first appears subtly in the toes and feet as reduced sensation, proprioception, or push-off strength. Once these diminish, the cascade toward frailty begins. As gerontologist Luigi Ferrucci observed, “Mobility is the most fundamental expression of independence, and its loss is the beginning of the end” (Ferrucci et al., 2016).

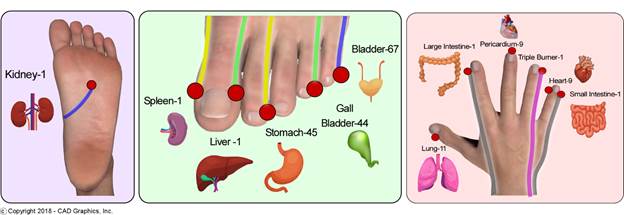

Meridians and Vital Energy Flow

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) expresses similar insights through the language of qi (vital energy) and meridians. Several of the body’s primary channels, including the Liver, Spleen, Stomach, Kidney, and Bladder, either begin or end at the toes (Maciocia, 2015). These meridians govern vital processes such as digestion, reproduction, and detoxification. Disruption of flow at the periphery is believed to reverberate inward, creating systemic disharmony.

As the Lingshu Jing (a companion text to the Neijing) states, “When the qi of the extremities is blocked, the organs within will suffer” (trans. Wu, 2008). In this paradigm, coldness, stagnation, or numbness in the toes are not trivial complaints but early signs of declining vitality, the first whispers of death’s approach.

Psychological Interpretation: Awareness, Neglect, and the Periphery of Consciousness

While the physiological layer of the aphorism highlights the body’s peripheral signals as early indicators of decline, the psychological dimension explores how awareness, or lack thereof shapes that process. In this context, “death” represents not just physical decay but the gradual erosion of vitality, engagement, and responsiveness to life’s subtleties.

Dissociation and Embodiment

Modern psychology has increasingly recognized the importance of embodiment, the lived experience of inhabiting one’s physical body, as essential to mental health and cognitive function (Durt, et al (2017). Yet, in contemporary societies characterized by sedentary lifestyles and disembodied digital existence, many people lose sensitivity to their physical selves. The feet and toes, distant from the brain and often ignored, become metaphors for the neglected peripheries of awareness.

This dissociation is not benign. Studies have shown that reduced proprioception and interoception, the senses of bodily position and internal state, correlate with anxiety, depression, and diminished cognitive function (Khalsa et al., 2018). In Jungian psychology, the shadow represents the disowned or unconscious aspects of the self. In a similar way, the body’s extremities can symbolize the “shadow” of bodily awareness, parts of ourselves we rarely think about but that profoundly shape our experience. Neglecting them reflects a broader neglect of the unconscious and the subtle.

The Psychology of Small Beginnings

The aphorism also teaches that decline begins with small lapses in attention. Cognitive-behavioral theorists note that habits, both constructive and destructive can emerge gradually through repeated micro-decisions (Neal et al., 2012). In the same way, death “beginning” in the big toe symbolizes the cumulative effect of minor neglect. A blister ignored becomes an infection; a sedentary day becomes a sedentary year. The toe, seemingly insignificant, becomes the starting point of a larger process of decay.

Zen teachings mirror this concept. Master Dōgen wrote, “To neglect the small is to betray the great” (Shōbōgenzō, trans. Nishijima & Cross, 1994). Psychologically, the lesson is clear: by training awareness toward the smallest and most peripheral phenomena, the sensations in the toes, the first signs of imbalance, the whispers of discontent, one cultivates a capacity to intervene before decay becomes inevitable.

Spiritual Interpretation: Impermanence, Return, and the Subtle Path

At the spiritual level, “death begins in the big toe” is neither a physiological warning nor a psychological metaphor but a profound statement about impermanence and the nature of life itself.

Impermanence and the Gradual Approach of Death

Buddhist philosophy emphasizes that impermanence (anicca) is the fundamental characteristic of all conditioned phenomena. Life does not end abruptly but is a continuous unfolding of change, a river flowing toward the ocean of dissolution. Just as the body’s vitality wanes first at its extremities, so too does the soul’s departure begin subtly in the smallest changes of breath, the faintest shifts in sensation.

The Diamond Sutra reminds practitioners that “All conditioned things are like a dream, an illusion, a bubble, a shadow” (Red Pine, 2001). The big toe, as the furthest point from the body’s “center,” becomes a symbol of these subtle transitions. Death is not a singular event but a process that begins long before the final breath and the wise cultivate awareness of this process without fear.

The Circle of Return

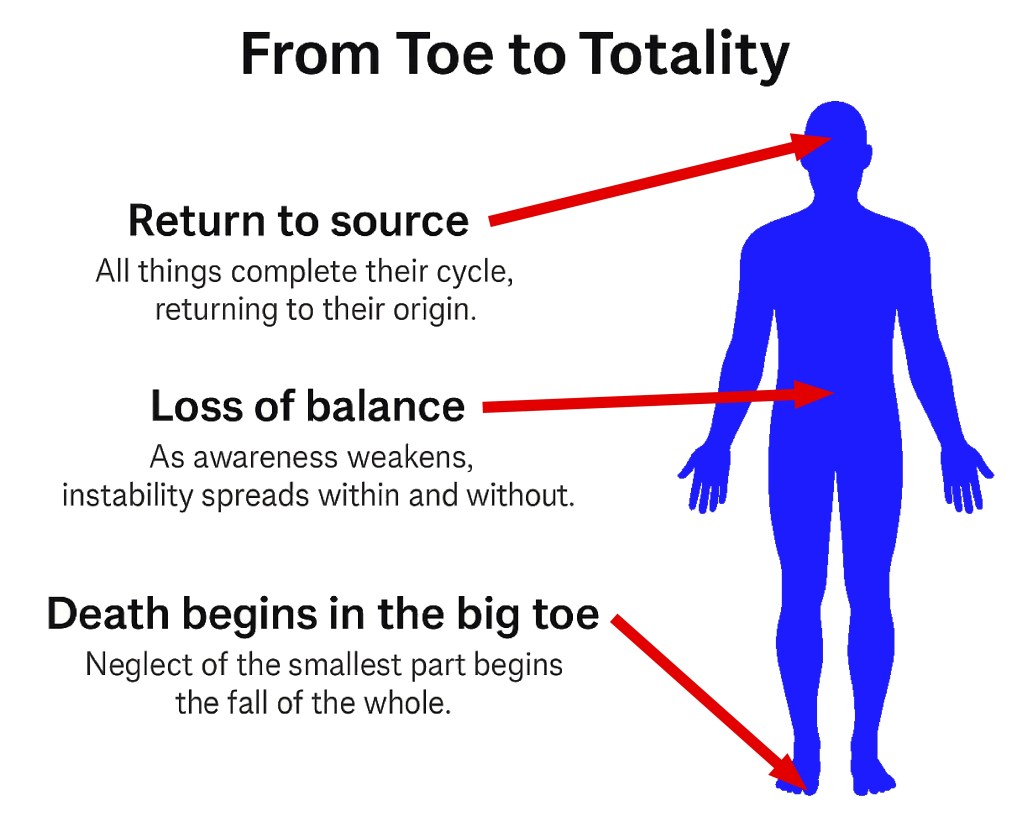

Taoist cosmology frames death not as an end but as a return to the source. “Returning is the motion of the Dao,” Laozi wrote (Tao Te Ching, trans. Addiss & Lombardo, 1993). In this framework, the toe is the starting point of walking while also becoming the place where the journey ends. The path that began with the first step returns to the same ground.

This cyclical vision is echoed in many traditional arts. In Taijiquan, for example, practitioners speak of “returning to the root” where physical, energetic, and spiritual processes are symbolized by grounding through the feet. As the root weakens with age, the spirit begins its return to the Dao. “Death begins in the big toe” thus becomes a poetic recognition of the natural rhythm of return: from periphery to center, from earth to heaven, from form to formlessness.

Integrative Perspective: Caring for the Small to Preserve the Whole

Across all three dimensions. physiological, psychological, and spiritual, a single principle emerges: the state of the whole is revealed in the condition of the periphery. The big toe, distant from the heart and often neglected, becomes both a literal and metaphorical early warning system. It tells us about the integrity of our circulation, the sharpness of our awareness, and the depth of our spiritual understanding.

In preventive medicine, this principle underlies the emphasis on foot care in diabetic patients, where early interventions at the level of the toes can prevent systemic complications (Boulton et al., 2005). In psychology, mindfulness practices that cultivate awareness of the body from the ground up improve interoception and reduce emotional dysregulation (Mehling et al., 2011). In spiritual disciplines, practices like walking meditation (baguazhang), standing meditation (zhanzhuang), and barefoot qigong remind practitioners to anchor their consciousness in the humblest and forgotten parts of the body.

To say that “death begins in the big toe” is therefore to issue a call for radical attentiveness — to the smallest sensations, the earliest signs of imbalance, and the often-ignored peripheries of our existence. It is a koan not about death, but about life: a reminder that to live fully is to remain awake even to the faintest signals of change.

Big Toe as a Symbol of Decline and Awareness Across Three Dimensions

| Dimension | Meaning of “Death Begins in the Big Toe” | Key Insights & Applications |

| Physiological | Early signs of systemic decline often appear first in the extremities (coldness, numbness, circulation issues, mobility loss). | – Toe and foot health reflect cardiovascular and neurological function. – Loss of gait speed or balance predicts mortality. – Meridians begin/end at the toes, blockages here affect the entire body. – Preventive care (mobility, balance, circulation) can slow aging. |

| Psychological | Neglect and dissociation often begin with the smallest, least noticed aspects of the self – the “periphery” of awareness. | – Reduced body awareness correlates with anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline. – Small acts of neglect accumulate into larger patterns of decay. – Training awareness of subtle sensations builds mindfulness and resilience. – Attention to the “shadow” parts of the self, fosters wholeness. |

| Spiritual | Death is a gradual return to source, beginning subtly and symbolically at the periphery – a process to be observed, not feared. | – Impermanence is revealed in subtle transitions. – The journey that begins with the first step returns to the same ground. – Awareness of small changes leads to acceptance of life’s cycles. – Practices like walking meditation and grounding cultivate spiritual presence. |

Conclusion

The Chinese saying “death begins in the big toe” is more than a quaint proverb. It is a concise expression of a deep and timeless truth: that decline, decay, and death all begin subtly, in places and ways we are least likely to notice. Physiologically, the toe is the frontier where circulatory weakness, neuropathy, and frailty first manifest. Psychologically, it symbolizes the peripheries of awareness, where neglect and dissociation take root. Spiritually, it represents the cosmic rhythm of impermanence, where the journey back to the source begins in the smallest steps.

Ultimately, the koan invites us to approach life with a heightened sensitivity, to honor the periphery as we do the center, to care for the small as we do the great. It teaches that the path to vitality, wisdom, and even enlightenment often begins not with dramatic gestures but with the humble act of noticing what is happening beneath our feet.

References:

Abellan van Kan, G., Rolland, Y., Andrieu, S., Bauer, J., Beauchet, O., Bonnefoy, M., Cesari, M., Donini, L. M., Gillette Guyonnet, S., Inzitari, M., Nourhashemi, F., Onder, G., Ritz, P., Salva, A., Visser, M., & Vellas, B. (2009). Gait speed at usual pace as a predictor of adverse outcomes in community-dwelling older people an International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (IANA) Task Force. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 13(10), 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-009-0246-z

Addiss, S., & Lombardo, S. (Trans.). (1993). Tao Te Ching. Hackett.

Boulton, A. J. M., Armstrong, D. G., Albert, S. F., Frykberg, R. G., Hellman, R., Kirkman, M. S., … & Sanders, L. J. (2005). Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment: A report of the task force of the foot care interest group of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care, 31(8), 1679–1685. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-9021

Cleary, T. (1998). Zen Essence: The Science of Freedom. Shambhala.

Criqui, M. H., & Aboyans, V. (2015). Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circulation research, 116(9), 1509–1526. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303849

Durt, C., Fuchs, T., & Tewes, C. (Eds.). (2017). Embodiment, enaction, and culture: Investigating the constitution of the shared world. Boston Review. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-28670-000

Ferrucci, L., Cooper, R., Shardell, M., Simonsick, E. M., Schrack, J. A., & Kuh, D. (2016). Age-Related Change in Mobility: Perspectives From Life Course Epidemiology and Geroscience. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 71(9), 1184–1194. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw043

Hamburg, N. M., & Benjamin, E. J. (2009). Assessment of endothelial function using digital pulse amplitude tonometry. Trends in cardiovascular medicine, 19(1), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2009.03.001

Khalsa, S. S., Adolphs, R., Cameron, O. G., Critchley, H. D., Davenport, P. W., Feinstein, J. S., … & Zucker, N. (2018). Interoception and mental health: A roadmap. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(6), 501–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.12.004

Laozi. (1993). Tao Te Ching (S. Addiss & S. Lombardo, Trans.). Hackett. https://archive.org/details/taoteching0000laoz_l1p2

Maciocia, G. (2015). The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

Mehling, W. E., Wrubel, J., Daubenmier, J. J., Price, C. J., Kerr, C. E., Silow, T., Gopisetty, V., & Stewart, A. L. (2011). Body Awareness: a phenomenological inquiry into the common ground of mind-body therapies. Philosophy, ethics, and humanities in medicine : PEHM, 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-5341-6-6

Neal, D. T., Wood, W., & Quinn, J. M. (2006). Habits—A Repeat Performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(4), 198-202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00435.x

Nishijima, G., & Cross, C. (1994). Shōbōgenzō: The True Dharma Eye Treasury (Vol. 1). Windbell.

Red Pine. (2001). The Diamond Sutra: The Perfection of Wisdom. Counterpoint.

Studenski, S., Perera, S., Patel, K., Rosano, C., Faulkner, K., Inzitari, M., Brach, J., Chandler, J., Cawthon, P., Connor, E. B., Nevitt, M., Visser, M., Kritchevsky, S., Badinelli, S., Harris, T., Newman, A. B., Cauley, J., Ferrucci, L., & Guralnik, J. (2011). Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA, 305(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1923

Unschuld, P. U., Jr. (2003). Huang Di nei jing su wen. University of California Press. https://ia801208.us.archive.org/9/items/huang-di-nei-jing-su-wen/Huang%20Di%20nei%20jing%20su%20wen.pdf

Wu, J. (2008). Ling Shu: The Spiritual Pivot. University of Hawaii Press.