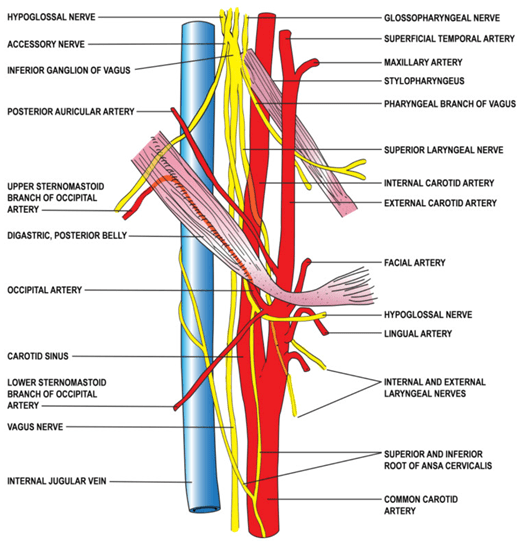

Although the vagus nerve is not directly stretched or compressed during normal cervical rotation, turning the head to the left produces well-documented functional effects on vagal tone. The vagus travels through the carotid sheath along with the internal jugular vein and carotid artery, all of which are influenced by head position. When the head rotates left, the right carotid sheath experiences mild elongation while the left side shortens, altering the tension patterns of the surrounding fascia and connective tissues. Studies show that cranial nerves, including the vagus, transmit mechanical forces through their perineural sheaths, meaning that changes in cervical fascial tension can influence the nerve’s functional environment without producing harmful compression (Wilke et al., 2017). Additionally, rotation modifies the hemodynamics of the internal jugular vein, subtly shifting the pressure dynamics adjacent to the vagus nerve (Zhou et al., 2022).

Head rotation also affects autonomic balance through the carotid sinus baroreceptors, which are located bilaterally along the internal carotid artery. These mechanosensitive receptors respond to tissue deformation during rotation, increasing afferent signals to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the brainstem. The NTS integrates baroreceptor input and modulates parasympathetic output through the vagus nerve (Chapleau & Abboud, 2020). As a result, turning the head to the left can modestly increase vagal activity, leading to decreased sympathetic tone, mild reductions in heart rate, and an overall calming effect. This mechanism explains why some individuals experience relaxation, lightheadedness, or parasympathetic settling during slow, sustained cervical rotation.

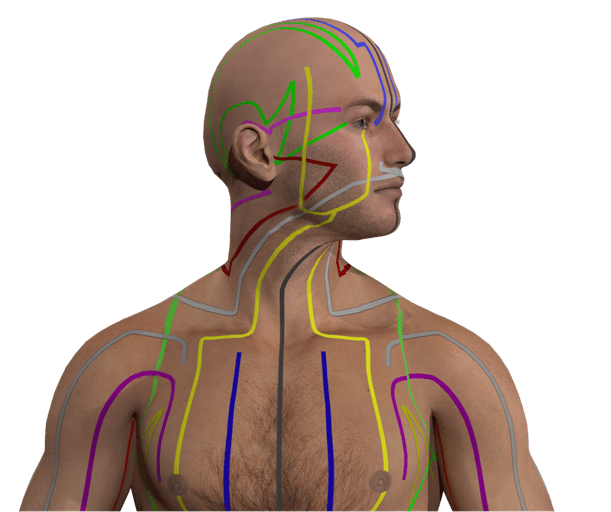

These modern findings complement traditional practices in Tai Chi, Qigong, and Dao Yin, where gentle head turning is used to regulate internal balance and calm the mind. Cervical rotation influences both the fascial network and the autonomic nervous system, creating a physiological basis for classical teachings on opening meridians, regulating Qi in the upper Jiao, and settling the shen (spirit or consciousness). When practiced with coordinated breathing, head rotation enhances respiratory sinus arrhythmia and further strengthens vagal tone, aligning ancient somatic wisdom with contemporary neurophysiology. Thus, the simple act of turning the head becomes a multidimensional practice of neurological, physiological, and energetic, that harmonizes the mind-body system.

1. Vagus Nerve + Carotid Sheath + Effects of Head Turning

When the head rotates to the left:

- The right carotid sheath (containing the vagus nerve, internal jugular vein, and carotid artery) becomes slightly elongated, increasing fascial tension around the right vagus nerve.

- The left carotid sheath slightly shortens, reducing tension.

- The carotid sinus on the left side may be gently stimulated as the tissues shift and rotate, activating baroreceptors.

- Baroreceptor firing sends signals to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the brainstem, which in turn increases parasympathetic (vagal) output and slightly decreases sympathetic tone.

- The internal jugular vein, which lies directly adjacent to the vagus nerve, experiences flow changes during rotation—altering the mechanical environment of the vagus nerve without compressing it.

This creates a functional parasympathetic adjustment, not a structural change.

2. Tai Chi / Qigong / Dao Yin Interpretation

In traditional Tai Chi, Qigong, and Dao Yin systems, turning the head is never just a mechanical action, but rather it is an autonomic, energetic, and fascial balancing maneuver. Modern neurophysiology now helps explain why ancient practitioners described head turning as calming, centering, and “opening the channels.”

A. Cervical Spiraling Opens the Upper Jiao

Gentle rotational movements lengthen one side of the neck while softening the other. In TCM terms, this affects:

- Lung meridian (Taiyin)

- Large intestine meridian (Yangming)

- Stomach/Spleen fascia

- Upper Jiao Qi dynamics

In modern terms, this mirrors changes in:

- Vagal tension

- Baroreflex sensitivity

- Jugular flow

- Cervical proprioceptive input to the brainstem

This produces an immediate calming effect, what modern clinicians call increased vagal tone, and what classical teachers called settling the shen.

B. Head Turning + Breath = Amplified Parasympathetic Response

When the head turns left while breathing slowly, three systems synchronize:

- Vagal afferent signaling (mechanically modulated via carotid sinus)

- Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (slow diaphragmatic breathing increases vagal firing)

- Cervical proprioception (upper spine movement reduces sympathetic output)

This synergy explains why Qigong forms such as:

- “Looking Left and Gazing Right”

- Ba Duan Jin #7 “Punching with Steady Eyes”

- Dao Yin head/neck spirals

are profoundly relaxing and centering.

Ancient language: “Qi descends, Shen becomes clear.”

Modern language: “Vagal tone rises, prefrontal cortex stabilizes.”

C. The Brainstem Connects the Energetic & Physiological Models

The vagus nerve’s nuclei:

- NTS (sensory integration)

- Dorsal motor nucleus

- Nucleus ambiguus

are directly influenced by cervical rotation.

This provides the bridge between:

- Energetic models: opening channels, balancing Yin/Yang of the neck

- Neurophysiology: altering baroreflex input to stabilize heart rate, calm limbic reactivity

This is why even subtle head turning in Tai Chi or meditation immediately shifts internal state. It is both energetic and neurological.

References:

Chapleau, M. W., & Abboud, F. M. (2020). Autonomic regulation and baroreflex mechanisms. Comprehensive Physiology, 10(2), 675–702. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c190015

Garner, D. H., Kortz, M. W., & Baker, S. (2023, March 11). Anatomy, head and neck: carotid sheath. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519577/

Wilke, J., Schleip, R., Yucesoy, C. A., & Banzer, W. (2017). Not merely a protective packing organ? A review of fascia and its force transmission capacity. Journal of Applied Physiology, 124(1), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00565.2017

Zhou, J., Khatri, M., & Hasan, D. M. (2022). Internal jugular venous dynamics during head rotation: Implications for cervical vascular flow. Journal of Vascular Research, 59(4), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1159/000524993