A Detailed Review of Long-Form Practices, Cognitive Limits, and Contemporary Application

With nearly 45 years of continuous study, practice, and teaching in the internal martial arts, I offer this article as both a practitioner and researcher deeply immersed in the tradition of Baguazhang. My experience spans several influential branches of the art, including Sun, Cheng, Emei, and Chung styles. Each has contributed to my understanding of the circular, spiraling, and dynamic principles that make Baguazhang a unique and profound martial system.

While I have not personally trained in Qing Gong (known in some Korean traditions as Kyong Gong Sul Bope), I have invested considerable time researching its historical claims, theoretical foundations, and relationship to internal martial development. My aim is not to present mystical exaggerations, but to critically examine the structure, feasibility, and legacy of extensive martial systems—particularly those that claim hundreds of forms, internal skillsets, and unique training regimens.

This perspective is informed by decades of firsthand teaching experience, cross-style comparison, academic inquiry, and dialogue with both traditional lineage holders and modern researchers. The views presented here are grounded in practice, supported by analysis, and guided by a sincere respect for the martial arts as a lifelong path of cultivation.

I. Introduction

Throughout the world’s martial traditions, extensive sequences of linked movements commonly referred to as forms, kata, hyung, taolu, or jurus, have been used as vehicles for transmitting fighting techniques, internal energy development, and philosophical insight. While some of these forms are brief and focused, others contain hundreds of techniques, and some practitioners claim that it may take 1 to 5 hours to complete in a single execution. This essay examines:

- The global context of long-form martial arts

- The feasibility of attaining proficiency in complex systems

- The practical application of such training in today’s fast-paced world

- Whether it is realistic or even possible for one or a few individuals to retain and transmit massive bodies of knowledge like 640 foundational sets and 108 BaguaZhang transitions

- And whether this model can thrive in modern martial arts culture

II. Global Martial Arts Traditions with Long-Form Practice

Numerous systems around the world preserve extended forms or sequences. These practices vary in complexity, purpose, and duration, but share the intention of transmitting depth of method and cultivating physical and internal mastery.

Chinese Martial Arts

- Yang-style Taijiquan: The traditional long form consists of 108 postures, often practiced in 30–60 minutes, or up to 2 hours with slow breathwork.

- Chen-style Taiji Laojia Yilu: A spiral-based internal form with 74–83 postures, taking about 45–90 minutes.

- Shaolin Luohanquan: Includes 18, 36, 72, or 108 movement forms, sometimes representing stages of internal/spiritual development.

- Baguazhang: Features 64 or 108 palm changes, practiced with circle walking and flowing transitions, often extending practice well over 1–2 hours.

Japanese Martial Arts

- Karate Kata: Systems like Shotokan include forms such as Kanku Dai, Unsu, or Suparinpei, each with dozens of transitions.

- Koryu Bujutsu: Ancient samurai traditions preserve long weapon kata or omote, ura, and kumitachi, each embedded with strategy and timing.

- Aikido: Though less formalized, Aikido includes long paired exercises with weapons like jo and bokken.

Korean Martial Arts

- Taekwondo (Poomsae) / Tang Soo Do (Hyung): Structured sequences like Tae guk or Pyong Ahn, progressing in complexity and coordination.

- Kuk Sool Won: Incorporates striking, joint locks, acrobatics, and traditional weapon forms.

Indian and Southeast Asian Systems

- Kalaripayattu: Utilizes meypayattu (body flows) and kalari vaittari (commanded sequences) for strength and agility.

- Silambam: Weapon forms with long rhythmic staff patterns.

- Pencak Silat: Includes complex jurus and langkah systems.

Internal Cultivation & Daoist Systems

- Yi Jin Jing / Xi Sui Jing: Monastic routines of 49–100+ stages, possibly performed over 3+ hours.

- Neigong & Dao Yin: Breath-driven meditative movement sets that stretch across 1 to 2-hour daily sessions.

- Baguazhang Switching Drills: 108 transitional palms (Top, Middle, Lower, with 36 each) used in continuous combat flow.

III. System Outline: Time and Structure

The following system components were provided from a particular lineage that I am quite familiar with. Each one has been analyzed based on estimated duration and modern feasibility.

Training Duration Feasibility

| Training Aspect | Duration | Feasibility Summary |

| Short Hyung (Dan Hyung) | 5–35 minutes | ✅ Very feasible with focused repetition. Excellent for limited-time sessions. |

| Middle Hyung (Joong Hyung) | 10–45 minutes | ✅ Highly feasible for modern practice. Allows depth, review, and memorization. |

| Long Hyung (Chang Hyung) | 1.5–5 hours | ⚠️ Feasible only in segments. Full-form execution is rare in modern life. Requires commitment and memory structuring. |

| Ship Pal Gae (18 Weapons) | 30–90 minutes each | ⚠️ Possible with rotation and yearly focus on 1–2 weapons at a time. Full mastery over a decade+ is realistic. |

| Wae Gong, Nae Gong, Kyong Gong Sul Bope (640 foundational sets) | Variable | ⚠️ Theoretically possible but better approached modularly. Depth over breadth. Grouped by body type or principle. |

| Bagua Zhang Switching Drills (108) | 1 sec per transition | ✅ Very feasible. Develops into fluid combinations. Excellent daily integration into circle walking and form. |

IV. BaguaZhang Switching Techniques (108 Foundational Switches)

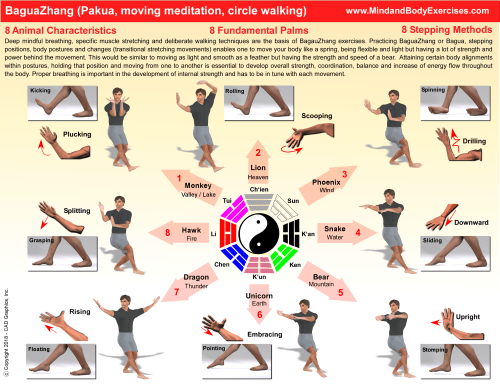

BaguaZhang Palm Changes & 108 Switching Techniques

- General Principles & Training Methods

- The “Eight Mother Palms” form the basis of Bagua internal development, practiced typically during circle walking. Each palm emphasizes body alignment, spiraling technique, and transitional mechanics (Chu, 2019).

- Expanded traditions (e.g., Yin or Gao styles) systematize palm changes into upper (top), middle, and lower transitions related to spiral alignment, kinetic linkages, and combat application.

- Historical Context & Lineage

- Founder Dong Hai Chuan’s students (Yin, Cheng, Gao lines) diversified the core palms into extensive sequences (e.g., 64-, 108-, or even 192-palm sets) (Chu, 2019).

- Practical Execution & Spiral Mechanics

- Palm change drills remain central to Bagua’s characteristic evasive and spiral movements. They are practiced either as stand-alone drills or integrated into walking the circular pattern.

- Overview of Switching Techniques

- In BaguaZhang (8 trigram palm) “switching” refers to the palm change, which is the fundamental dynamic movement that allows a practitioner to alter direction, intent, angle, or application while walking the circle. These palm changes are typically modular, allowing them to be strung together like language.

- Traditionally, Bagua styles such as Sun, Cheng, Yin, Gao, and Liang develop 8 core palm changes, which expand into multiple permutations and footwork variations. Advanced lineages (especially in Gao-style) systematize palm changes into top (Sung, middle (Jung), and lower (Ha) body initiations.

- Structure of 108 Switching Techniques

- 36 Top Switching Techniques (Sung)

- Initiated from the upper body:

- shoulders, arms, hands, and upper spine

- Often involve:

- Overhead swings

- Downward palms

- Cloud hands

- Strike deflections

- Rotational arm/shoulder mechanics

- Head-level entries or wraps

- Often involve:

- shoulders, arms, hands, and upper spine

- These are closely tied to Yang-like motion: expansive, expressive, outward

- Initiated from the upper body:

- 36 Middle Switching Techniques (Jung)

- Centered on the torso, hips, and waist

- Focus:

- Spiral rotations from Dantian

- Mid-line redirections

- Coiling waist motions to project energy

- Interception and bridging techniques

- 36 Lower Switching Techniques (Ha)

- Originate from the legs, footwork, stances, and dropping mechanics

- Include:

- Sweeps, low kicks, stepping traps

- Cross-stepping, deep pivots, root shifting

- Defensive dodges from low angles

- Include:

- Tend to reflect Yin-like qualities: inward, sinking, re-directive

- Originate from the legs, footwork, stances, and dropping mechanics

- 36 Top Switching Techniques (Sung)

- Integration into Practice

- Switching techniques may be performed as:

- Standalone drills (e.g., 5 switching drills per session)

- Embedded in circle walking routines

- Linked into forms or paired drills

- Many practitioners organize them seasonally (e.g., focusing on a layer for 3 months)

- Some styles break 108 into 3 series of 36, which are further divided into 8-technique families, often linked to elements or trigrams.

- Switching techniques may be performed as:

V. Wae Gong, Nae Gong, Kyong Gong Sul Bope (640 Foundational Sets)

These three terms of Wae Gong (external power), Nae Gong (internal cultivation) (Wikipedia contributors, 2024), and Kyong Gong Sul Bope (aerial or mystical skill), represent progressive layers of skill development. The inclusion of 640 foundational sets, divided by 8 hereditary types × 80 subsets, supports a detailed, modular training system.

Qing Gong translates literally to “light skill” or “lightness technique.” It refers to the ability to move the body lightly and rapidly, with agility and grace. While some Korean traditions refer to this as Kyong Gong Sul Bope, the broader and more recognized Chinese equivalent is Qing Gong, emphasizing aerial mobility, lightness, and rapid footwork to:

- Evade attacks

- Traverse difficult terrain

- Jump long distances or scale walls

- Appear to “float” or “glide”

Documented Components

| Component | Function | Modern Analog |

| Weighted step work | Builds leg power for jumping/landing | Plyometric training |

| Low stance work | Improves tendon recoil and gliding mobility | Isometric holds and tendon loading |

| Breath synchronization | Matches inhale/exhale to movement rhythm | Neigong, internal energy pacing |

| Climbing drills | Simulates wall-scaling, aerial coordination | Parkour, tactical wall-scaling drills |

Each body type would ideally have 80 tailored micro-sets, designed to:

- Compensation for biomechanical challenges

- Enhance strengths

- Reduce injury risk

- Maximize fluidity and function for that build

Each 80-set group may include drills or sequences from multiple domains. A sample distribution might look like:

Categories of the 80 Sets per Type

| Category | # Sets | Example Focus |

| Wae Gong (External Power) | ~30 | Striking forms, structural alignment, repetition drills |

| Nae Gong (Internal Cultivation) | ~20 | Breath-body integration, dantian rotation, meditative form |

| Kyong Gong Sul Bope (Aerial/Light Skill) | ~10 | Leaping drills, evasions, sudden weight shifts |

| Conditioning & Recovery | ~10 | Joint prep, tendon strength, recovery movement |

| Specialized Drills (Hybrid) | ~10 | Blending categories, such as explosive internal transitions |

Format of Each Set

Each “set” may be:

- A short form (30 sec to 2 minutes)

- A paired drill

- A static posture with breath regulation

- A moving neigong routine for soft-tissue engagement

- A dynamic jump/evasion/fall drill for Kyong Gong

These are not isolated movements but often sequential flows, comprising 5–12 linked actions, possibly with an internal theme or breathing rhythm.

Teaching and Rotation Strategy

Given the vast number of sets, a realistic teaching and retention method would require:

- Rotational cycles, focusing on 10–15 sets per quarter

- Tracking logbooks for both teacher and student

- Core sets used for all types (e.g., the “seed drills”)

- Some sets exclusive to a body type (e.g., “Overweight” sets avoid deep stances early on)

VI. Training Frequency and Feasibility Over Time

✅ Ideal Scenario (1–2 hrs, 5–6 days/wk)

- Entire system could be internalized over 20–30 years

- Structured cycles (e.g., seasonally rotating weapon or form focus)

- Internal cultivation and external technique blended over time

⚠️ Modern Constraints (1 hr, 3–4 days/wk)

- Prioritize core sets over totality

- Short and middle hyung are realistic anchors

- Bagua transitions and foundation sets can be explored in small segments

- Weapon work limited to 2–3 tools over 5–10 years

Best Practices

- Modular training: Break long forms into repeatable segments

- Cyclic review: Return to previously learned sets on a schedule

- Specialization: Focus on the sets or weapons that resonate with your goals or body constitution

- Documentation: Journaling and visual diagrams to reinforce memory

- Teaching: Sharing builds retention and embodiment

VII. Cognitive and Cultural Considerations

Cognitive Feasibility

- Human experts can recall and perform thousands of patterns over decades (Ericsson et al., 1993)

- Long-term memory improves with emotional connection, repetition, and teaching

- Martial knowledge is embodied, or stored not just mentally but within somatic muscle memory and rhythm

Cultural Challenge

- Modern society favors speed, variety, and instant results

- Systems requiring 20–50 years of investment are often devalued

- Traditional transmission (oral, demonstrated, internalized) is at odds with certification-based or commercialized martial arts

VIII. Can One or a Few Masters Truly Preserve a System This Vast?

✅ Yes – Extraordinary but Not Fantastical

Many monastic, Daoist, orclassical lineage systems have survived due to one or two deeply committed masters per generation. This requires a lifestyle, not a hobby. It is not for the casual martial artist—but it is possible and historically supported.

Feasible if the practitioner:

- Lives in immersion

- Teaches regularly

- Revisits the material cyclically

- Structures forms by thematic grouping

However:

- System survival depends on generational transmission

- Modern students may need a modularized curriculum to digest the material

- The original system may evolve, fragment, or reduce as common in many traditions

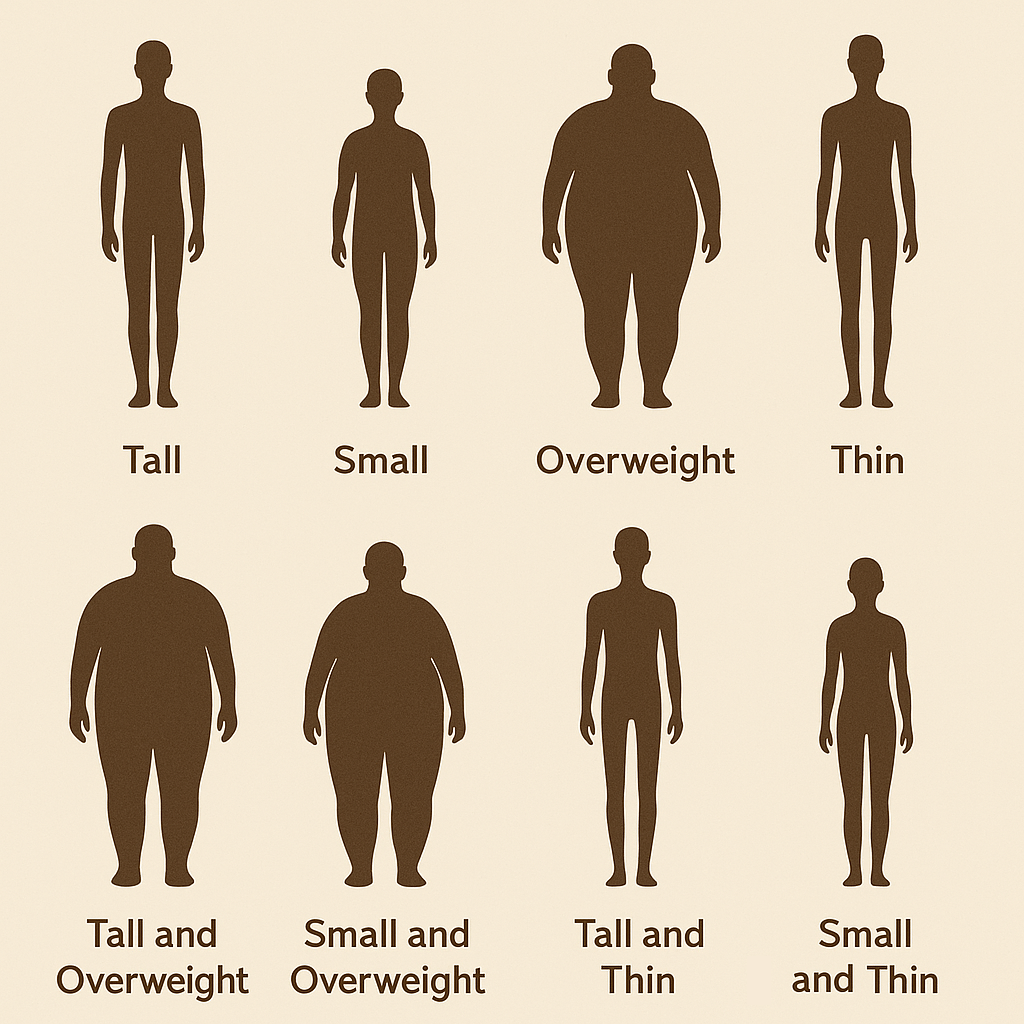

IX. Hereditary Body Types: Intelligent Design or Marketing Gimmick?

An important aspect of the system under discussion is its claim to include 640 foundational sets distributed across eight hereditary body types. This principle asserts that different forms, drills, or techniques are tailored to suit constitutional differences, physiological predispositions that affect movement mechanics, balance, and energy expression.

8 Different Hereditary Types:

- Tall

- Small

- Overweight

- Thin

- Tall and Overweight

- Small and Overweight

- Tall and Thin

- Small and Thin

This categorization may seem simplistic at first glance, but it reflects a long-standing tradition in systems such as:

- Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM): Uses somatotype constitution in diagnosis and qigong prescription.

- Ayurveda: Categorizes body-mind types (e.g., Vata, Pitta, Kapha).

- Martial Lineages: Where forms were adapted to suit a practitioner’s build, power-to-weight ratio, and flexibility.

- Biomechanical profiling in sports science

The claim that each of these eight types has access to a specific family of foundational sets suggests a physiologically intelligent system. However, it requires rigorous documentation and consistent application to be credible.

X. Extraordinary Claims Require Extraordinary Evidence

In martial arts and indeed any traditional system, the sheer number of levels, forms, sets, movements, and training layers may raise skepticism, especially when:

- Not recognized by peers

- Lacking written historical lineage

- Missing corroborative physical proof (e.g., preserved manuals, photographic/video documentation, public demonstrations)

Principle of Skepticism:

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

Popularized by Carl Sagan, this principle remains relevant when evaluating martial systems. If a school or master claims:

- 640 unique foundational sets

- 108 specialized Bagua transitions

- Dozens of long forms taking hours to complete

Then, the burden of proof falls upon the claimant to:

- Produce lineage records

- Provide structured curriculum or teaching materials

- Demonstrate practical proficiency in said material

This isn’t to challenge the sincerity of the tradition, but rather to reinforce credibility and transparency in a world where esoteric claims are often made without accountability.

XI. The Problem of Deception: Buyer Beware

There are, unfortunately, martial groups and individuals who leverage the allure of ancient, secret, or overly complex systems to:

- Elevate their authority

- Shield scrutiny through obscurity

- Create dependence among students

⚠️ Red Flags in Questionable Systems:

- Inability to demonstrate claimed techniques

- Unverifiable lineage (or lineage constantly evolving to fit narrative)

- Overuse of mysticism or secrecy to justify lack of transparency

- Commercial exploitation (e.g., charging for levels with no meaningful advancement)

✅ Student Guidelines for Due Diligence:

- Ask for documentation (written, photographic, curriculum outlines)

- Observe public demonstrations or request private proof of capacity

- Cross-reference claims with outside martial scholars or historians

- Follow your intuition. If something feels manipulative, it likely is

True mastery does not hide behind jargon or cult-like authority. It is revealed in clarity, function, humility, and the ability to teach and demonstrate.

XII. Reinforcing a Balanced Perspective

While skepticism is essential, we must not lose sight of this:

Some traditional systems do legitimately carry vast knowledge, passed from generation to generation, often in difficult-to-document formats.

However, those systems tend to demonstrate:

- Consistent internal logic

- Observable results

- Coherent pedagogy

- Recognition from external peer groups, even across style lines

In today’s environment, a balance between open-mindedness and critical thinking is necessary. One must neither accept everything at face value nor reject ancient systems outright simply because they differ from modern expectations.

XIII. Conclusion

The legacy of massive martial systems, with hundreds of forms and transitional movements, is not a fantasy. A martial arts system that claims hundreds of techniques across hereditary types, multi-hour forms, and internal training deserves to be listened to, but not blindly believed. If it stands up to scrutiny, produces capable students, and provides reproducible results, then it should be valued as part of our shared martial legacy.

It is an extraordinary path, one that demands lifelong dedication, deep internalization, and cultural adaptation. While the complete memorization and performance of such a system is unlikely for the average modern student, it is feasible for a dedicated practitioner or lineage holder, particularly if approached intelligently and methodically.

In today’s world, success lies not in grasping everything at once, but in embodying a part of the system deeply enough to preserve its essence. If not, then as always: Caveat emptor: Buyer beware.

References

Chinese martial arts training manuals : a historical survey : Kennedy, Brian, 1958- : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive. (2005). Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/chinesemartialar0000kenn.

Chow, D., & Spangler, R. (1982). Kung Fu: History, Philosophy, and Technique.

Chu, F. (2019) Baguazhang — Overview. https://shaolin.org/general-3/research/baguazhang/all.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Comprehensive Asian fighting arts : Draeger, Donn F : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive. (1980). Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/comprehensiveasi0000drae

Ericsson, Karl & Krampe, Ralf & Tesch-Roemer, Clemens. (1993). The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Psychological Review. 100. 363-406. 10.1037//0033-295X.100.3.363.

Henning, S. E. (1999). Academia encounters the Chinese martial arts. DeepDyve. https://www.deepdyve.com/lp/university-of-hawai-i-press/academia-encounters-the-chinese-martial-arts-XdDBjABJdT

Sagan, C. (1996). The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. New York: Random House.

Shahar, M. (2008). The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. University of Hawaii Press.

Shing, T. C. (2020b). Xiantian Bagua Zhang: Gao Style Bagua Zhang – Circle Form. Singing Dragon.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, June 26). Baguazhang. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baguazhang?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Wikipedia contributors. (2024, July 8). Neigong. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neigong?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Yang, Jwing-Ming. (1996).The Root of Chinese Qigong. YMAA Publications.