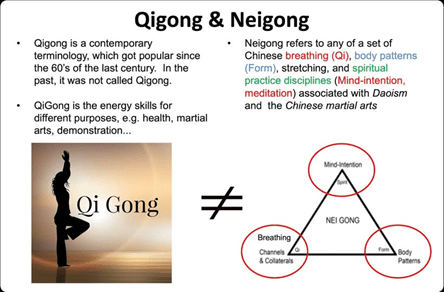

Korean neigong, or internal cultivation, represents a rich and multifaceted tradition rooted in the intersections of Seon (Zen) Buddhism, Daoism, indigenous shamanism (Muism), and martial arts. Though often compared to Chinese neidan (internal alchemy), Korean systems possess their own unique methods, spiritual philosophies, and training structures. These practices cultivate internal strength, breath control, meditative awareness, and according to lineage traditions, can even develop extraordinary energetic capabilities within the human body.

Foundations of Korean Internal Cultivation

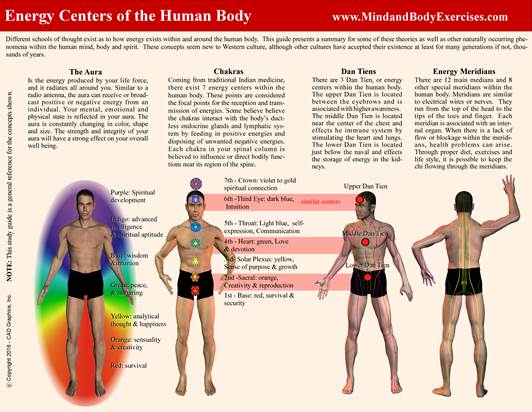

At the core of Korean neigong is the concept of danjeon training, the Korean analog to the Chinese dantian, representing energy reservoirs in the lower abdomen, heart center, and forehead. Training typically begins with breath regulation (hoheupbeop), emphasizing deep abdominal breathing and the storage of gi (qi), in the lower danjeon. Complementary postural training fosters rootedness and structural alignment to optimize energetic circulation.

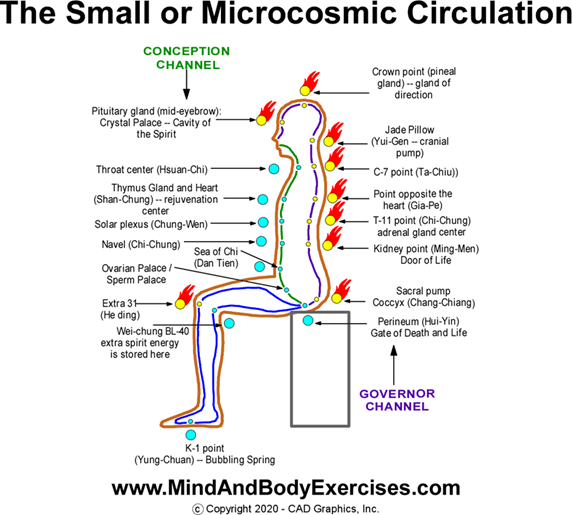

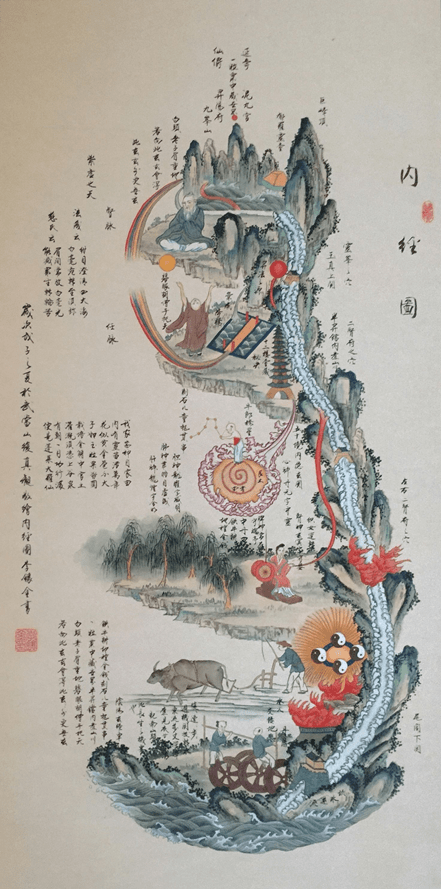

Breathing practices are often paired with dynamic postures (dong gong) and stillness meditation (jing gong). Stillness can take the form of seated meditation (jwaseon), standing meditation (ipseon), or lying meditation (woseon). These practices are further enhanced by internal visualizations and energy circuit training (e.g., small celestial circulation (so cheon-ju), echoing the microcosmic orbit known in Daoist internal work.

Ethical cultivation is not separated from physical training. In Seon Buddhism, self-discipline, clarity of mind, and non-attachment are prerequisites for deeper spiritual realization. Korean shamanism and folk practices also include cathartic or vibrational techniques intended to release emotional and energetic blockages (Kendall, 2009).

I. Core Practices in Korean Neigong

1. Breathing Techniques

- Emphasis on abdominal breathing focused on the danjeon, Korea’s equivalent to dantian

- Breath retention and pressurization techniques to build internal heat and energy

2. Danjeon Development

- Training begins with the lower danjeon as the energy reservoir, with advanced practice involving the middle and upper danjeon

- Strengthening of energy through posture, breath, and mental focus

3. Stillness & Movement Forms

- Alternation between static meditation (jing gong) and dynamic exercises (dong gong)

- Includes seated (jwaseon), standing (ipseon), and walking meditations (Wŏnhyo. (2007)

4. Energy Circulation Pathways

- Refinement of energy through microcosmic and macrocosmic orbit-like methods

- Known in Korean as So Cheon-ju and Dae Cheon-ju, reflecting small and great celestial circuits

5. Vocal Resonance and Chanting

- Use of sound (vibration or mantra) to stimulate meridians or brain centers

- Buddhist hwadu practice or shamanic incantations are used for energetic activation (Kendall, 2009)

6. Moral and Spiritual Development

- Cultivation of shin (spirit) and refinement of ki (qi) is inseparable from ethical living, compassion, and clarity of mind

- These echo the Confucian and Buddhist emphasis on inner purity (Buswell, 2007)

II. Stages of Progression in Neigong

Korean systems typically follow a three-phase transformation of internal substances, paralleling Daoist inner alchemy:

| Stage | Focus | Goal |

| 1. Jeong | Essence | Cultivation and storage in lower danjeon |

| 2. Ki | Energy | Circulation through meridians, activation |

| 3. Shin | Spirit | Enlightenment, calm, and intuitive awareness |

This structure reflects a philosophical progression from form to formlessness, body to spirit, and effort to naturalness (mu-shim).

III. Structured Systems in Lineage-Based Curricula

Some While historical documentation of standardized curricula is limited, several lineage-based or temple-administered systems reveal structured sequences of internal exercises.

1. Sunmudo

Sunmudo, a Korean Zen martial art maintained at Golgulsa Temple, exemplifies a synthesis of Seon meditation, martial forms, and yogic movement. Training includes:

- Breathing forms for energy refinement

- Dynamic martial sequences for vitality and physical strength

- Sitting meditation to deepen spiritual awareness

While specific counts of exercises vary, temple curricula often include dozens to hundreds of postures practiced cyclically and ceremonially (Gatling & Svinth, 2010; Buswell, 1992).

2. Sundo (Kouk Sun Do)

Sundo is a Daoist-based system emphasizing long-term energetic development through structured, belt-ranked progressions:

- Early stages introduce forms of 20–30 postures each, integrating breath and motion

- Intermediate levels include multiple 10–12 posture forms with increased internal pressure

- Higher ranks culminate in single postural meditations held for long durations

Though no canonical source confirms the existence of 640 exercises, advanced Sundo practitioners speak of multiple series comprising dozens of unique sequences, many kept orally or within private manuals (Baker, 2008).

3. Private and Temple-Based Neigong Curricula

Certain modern Daoist-influenced schools teach internal cultivation through sequential stages such as:

- Ming Jin – Obvious or external power

- An Jin – Hidden or internalized power

- Hua Jin – Transformative or refined power

Each stage includes multiple breathing patterns, static postures, shaking or loosening exercises, and visualization practices. While primarily documented in Chinese systems, some Korean offshoots follow similar developmental arcs (DaoistMagic.com, 2018).

IV. The 640 Neigong Foundation Exercises

The “640 foundational exercises” for neigong training is an intriguing concept. While there seems to be no standardized system in Korea or China universally recognized by that number, similar structured sets have been mentioned in some martial and internal arts traditions.

Possible explanations:

- Categorized Curricula: Some advanced traditional neigong systems (especially temple-based or private transmission lineages) are reported to have hundreds of discrete exercises, including:

- Static postures (standing, seated)

- Dynamic movements

- Meridian tapping or shaking

- Breath-retention patterns

- Visualizations or inner orbits

- Numerical Symbolism: The number 640 may also be symbolic or organizational, reflecting a highly structured internal system for advanced practitioners. Comparable systems:

- 72 movements in Sundo

- 108 prostrations in Seon Buddhism

- 360 meridian-related points, often doubled for bilateral flow

- Private or Temple Transmission: It’s plausible that a master or temple in Korea (or China) compiled a curriculum totaling 640 methods as part of a closed-door (munpa) tradition, though no academic or published source verifies this number explicitly.

V. Reports of Extraordinary Abilities and Energy Mastery

Anecdotal reports from both Korean and Chinese internal arts describe practitioners capable of moving energy to specific areas of the body at will, producing heat, shaking, or subtle vibration. Some traditions describe this as “naegong hwa” (internal fire) or “danjeon activation.”

In neijia (internal martial arts) circles, Chinese masters have demonstrated:

- Fa jin – Explosive internal force from still postures

- Intentional energy projection through limbs or meridians

- Energetic sensitivity during partner work, reflecting advanced internal perception

While these claims lack robust scientific verification, ethnographic accounts support that dedicated practice over years may result in unusually fine motor control, breath retention capacity, and subjective energetic awareness (Buswell, 1992; ResearchGate, 2021).

In Korean contexts, practitioners of Sunmudo and Sundo have similarly reported the ability to move internal energy in ways that affect circulation, body temperature, or mental state. These effects are typically cultivated over decades of intensive, daily practice in monastic or semi-monastic settings. However, it is important to address, that “extraordinary claims, require extraordinary evidence,” where a claim that is highly improbable or contradicts established knowledge, one should demand a higher standard of proof than for more ordinary claims. This principle, popularized by Carl Sagan, emphasizes that the strength of evidence needed to support a claim should be proportional to its degree of unusualness.

VI. Conclusion

Korean neigong is a dynamic and integrated tradition combining physical health, meditative stability, and moral clarity. Its practices span breath regulation, posture, mental focus, and internal energy movement, often embedded within temple or lineage-based systems.

While the concept of 640 foundational exercises remains unverified in published literature, structured multi-stage curricula in Sunmudo, Sundo, and other private lineages offer clear evidence of comprehensive internal development systems. Stories of energetic control or internal transformation continue to circulate in traditional circles, pointing to the long-term potential of dedicated inner practice, not necessarily as supernatural, but as refined physiological, neurological, and spiritual discipline.

References

Baker, D. L. (2008). Korean Spirituality. University of Hawai‘i Press. https://uhpress.hawaii.edu/title/korean-spirituality/

Buswell, R. E., Jr. (1992). The Zen Monastic Experience: Buddhist Practice in Contemporary Korea. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691034775/the-zen-monastic-experience

DaoistMagic.com. (2018). Neigong Training Curriculum Overview. Retrieved July 2025, from https://www.daoistmagic.com/neigong-training-class

Kendall, L. (2009). Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion. University of Hawai‘i Press. https://archive.org/details/shamansnostalgia0000kend

Gatling, L., & Svinth, J. (2010). Martial arts of the world: An Encyclopedia of History and innovation. http://www.academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/3159277/Martial_arts_of_the_world_An_Encyclopedia_of_History_and_innovation

ResearchGate. (2021). Hang the Flesh off the Bones: Cultivating an Ideal Body in Taijiquan and Neigong. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351059664

Wŏnhyo. (2007). Cultivating original enlightenment : Wŏnhyo’s Exposition of the vajrasamādhi-sūtra (Paperback edition). University of Hawaiʻi Press. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/13457065