Many people believe that a person’s brain only ever exercises 10% of its capacity.

The Potential for Extraordinary Human Abilities

For over a century, a persistent misconception has claimed that most people use only 3–10% of their brain capacity, while exceptional individuals, such as Albert Einstein supposedly accessed much more, some unique individuals perhaps even 100%. While appealing, this notion is unsupported by credible neuroscience. Modern research shows that humans use all parts of their brain over time, and differences in intellectual performance are due to efficiency, connectivity, and specialized skill development rather than large unused reserves.

The Origins and Fallacy of the “10% Brain” Myth

The “10% brain myth,” sometimes altered to 3%, 5%, or 8%, appears to have originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Early neuroscientists misunderstood the roles of various brain regions, sometimes labeling underexplored areas as inactive. Pioneer psychologist William James’s statement that “we are making use of only a small part of our possible mental and physical resources” was also misinterpreted as a literal statement about unused brain tissue rather than human potential (Beyerstein, 2004).

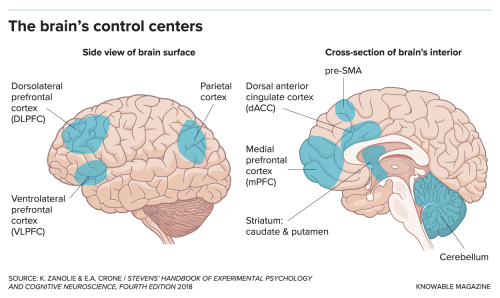

Today, brain imaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans clearly show that nearly all regions of the brain are active over the course of a normal day, even during rest and sleep (Raichle & Gusnard, 2002). Moreover, the brain’s high metabolic cost accounts for ~2% of our body weight but ~20% of resting energy expenditure, makes it implausible that most of it lies dormant (Attwell & Laughlin, 2001). Even minor injuries can cause significant deficits, further demonstrating that all areas contribute to normal function.

(Knowable Magazine Science Graphics Library, n.d.)

Einstein’s Brain: Anatomical Variations and Cognitive Implications

Albert Einstein appears to have never claimed to use a greater “percentage” of his brain than others. However, his preserved brain, examined by Dr. Thomas Harvey and later researchers, revealed several structural distinctions. Notably, Einstein’s inferior parietal lobules, which are critical for spatial reasoning, mathematical processing, and visual imagery, were about 15% wider than average (Witelson et al., 1999). Additionally, his Sylvian fissure pattern was atypical, allowing more cortical connectivity between mathematical and spatial areas. Increased glial cell ratios in certain regions may have provided enhanced metabolic support for sustained cognitive work (Witelson et al., 1999).

Einstein’s Documented Brain Features vs. Modern Trainable Extraordinary Abilities

| Einstein’s Documented Brain Features | Modern Trainable Extraordinary Abilities |

| Enlarged inferior parietal lobules – 15% wider than average, linked to advanced spatial reasoning, mathematics, and visual imagery (Witelson et al., 1999). | Spatial mastery through training – Architects, pilots, and martial artists develop exceptional spatial awareness via repeated practice and sensory-motor mapping. |

| Unusual Sylvian fissure pattern – Reduced fissure depth allowed more cortical connectivity between regions for math, spatial visualization, and abstract thinking (Witelson et al., 1999). | Cross-domain skill integration – Interdisciplinary study and problem-solving enhance connectivity between brain networks (e.g., combining art and engineering in design thinking). |

| Increased glial cell ratio – Higher density in certain regions, possibly providing better metabolic support for sustained thought. | Endurance of cognitive focus – Meditation, mindfulness, and cognitive endurance training improve attention regulation and mental stamina (Goleman, 2013). |

| High neuron density in integrative areas – Supports rapid processing of complex, abstract information. | Pattern recognition expertise – Chess masters, seasoned detectives, or experienced clinicians recognize subtle cues faster through accumulated experience (Kahneman & Klein, 2009). |

| Likely enhanced interhemispheric connectivity – Possibly allowing faster and richer information exchange between hemispheres. | Bilateral coordination training – Activities like music performance, ambidextrous martial arts practice, or juggling increase interhemispheric communication. |

| Innate neuroanatomical advantage from birth – Unlikely to be replicated through training alone. | Neuroplasticity-driven gains – Long-term skill practice in domains like language learning, navigation, or musical performance physically alters brain structure and function (Eagleman, 2023). |

These features likely supported Einstein’s remarkable ability to mentally visualize and manipulate physical concepts, as seen in his thought experiments on relativity. However, his genius also stemmed from decades of intense study, curiosity, and integrative thinking, all factors rooted in training and persistence rather than sheer anatomy.

Extraordinary Cognitive Abilities and the “Sixth Sense”

While the term “sixth sense” often evokes supernatural connotations, neuroscience recognizes several sensory modalities beyond the traditional five. These include proprioception (awareness of body position), vestibular sense (balance), and interoception (perception of internal bodily states). In certain individuals, these senses may be unusually acute, giving the impression of extraordinary perception.

Extraordinary abilities can arise from different mechanisms:

- Synesthesia involves cross-activation between sensory regions, sometimes enhancing memory or creativity.

- Savant syndrome allows individuals with developmental or acquired conditions to demonstrate exceptional skills in calculation, art, or memory.

- Intuitive expertise emerges when professionals make rapid, accurate judgments by subconsciously recognizing complex patterns from experience (Kahneman & Klein, 2009).

- Heightened situational awareness, often found in elite athletes, martial artists, or soldiers, develops through systematic training in sensory attention and pattern detection.

These capabilities are grounded in neuroplasticity, or the brain’s ability to reorganize and strengthen neural pathways through repeated use (Goleman, 2013). Sensory compensation, such as improved hearing in those with vision loss, also illustrates how the brain can refine and amplify perception in certain channels (Eagleman, 2023).

Conclusion

The myth that most humans use only a small fraction of their brain capacity is not supported by scientific evidence. Instead, differences in performance, whether in Einstein’s theoretical physics or in individuals demonstrating exceptional perception stem from variations in brain structure, connectivity, training, and experience. Einstein’s brain offered anatomical advantages that may have facilitated his unique style of thinking, but his genius was equally shaped by intellectual discipline and curiosity. Similarly, so-called “sixth sense” abilities are the result of heightened sensory integration, superior pattern recognition, and deliberate practice, illustrating that human potential is less about unlocking unused brain areas and more about refining and optimizing the capacities we already employ.

References:

Attwell, D., & Laughlin, S. B. (2001). An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 21(10), 1133–1145. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001

Beyerstein, B. L. (2004). Do we really use only 10 percent of our brains? (2024, February 20). Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/do-we-really-use-only-10/

Eagleman, D. (2023). Incognito: The secret lives of the brain. Pantheon. Incognito. https://eagleman.com/books/incognito/

Goleman, D. (2013). Focus: The hidden driver of excellence. Harper. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-37403-000

Kahneman, D., & Klein, G. (2009). Conditions for intuitive expertise: A failure to disagree. American Psychologist, 64(6), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016755

Knowable Magazine Science Graphics Library. (n.d.). The brain‘s control centers | Free educational graphics. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/knowablemag/53072741397

Raichle, M. E., & Gusnard, D. A. (2002). Appraising the brain’s energy budget. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(16), 10237–10239. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.172399499

Witelson, S. F., Kigar, D. L., & Harvey, T. (1999). The exceptional brain of Albert Einstein. The Lancet, 353(9170), 2149–2153. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10327-6