From Nobel Prize Recognition to Modern Reassessment

The therapeutic use of sunlight, also known as heliotherapy, has roots in ancient medicine. Cultures such as the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans prescribed sun exposure for health and vitality, believing it could improve physical and spiritual well-being (Holick, 2016). By the 19th and early 20th centuries, heliotherapy became widely adopted in Europe and North America as a treatment for conditions like rickets, skin diseases, and tuberculosis, particularly in sanatoria where sunlight and fresh air were emphasized (Sunlight, Outdoor Light, and Light Therapy in Disease Management, n.d.).

Nobel Prize Recognition

The scientific validation of light therapy was established through the work of Niels Ryberg Finsen. Finsen demonstrated that concentrated light, particularly ultraviolet rays, could be used to treat lupus vulgaris, a severe cutaneous form of tuberculosis. For this innovation, he was awarded the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “in recognition of his contribution to the treatment of diseases, especially lupus vulgaris, with concentrated light radiation” (Nobel Prize, 1903/2024). His research marked a pivotal moment in medical science, as it represented one of the earliest successful applications of light as a therapeutic modality (Grzybowski et al., 2016).

Decline of Traditional Sun Therapy

Despite its early success, enthusiasm for heliotherapy declined in the mid-20th century. The discovery of antibiotics, such as streptomycin in the 1940s, rendered heliotherapy obsolete for treating tuberculosis (Daniel, 2006). Furthermore, as scientific understanding of ultraviolet radiation advanced, physicians began to recognize the dangers of excessive sun exposure, including premature aging of the skin, immune suppression, and increased risk of skin cancers (Narayanan et al., 2010). Public health messages shifted from promoting unregulated sun exposure to encouraging cautious, limited exposure combined with sun protection.

Contemporary Perspectives

Today, sunlight is still acknowledged as vital for vitamin D synthesis, which is critical for bone health, immune regulation, and overall wellness (Holick, 2007). Modern medicine has also refined phototherapy, using specific wavelengths of artificial light for targeted conditions such as psoriasis, vitiligo, neonatal jaundice, and seasonal affective disorder (Roelandts, 2002). This demonstrates how the legacy of heliotherapy has evolved from generalized “sun cures” to scientifically controlled light-based treatments.

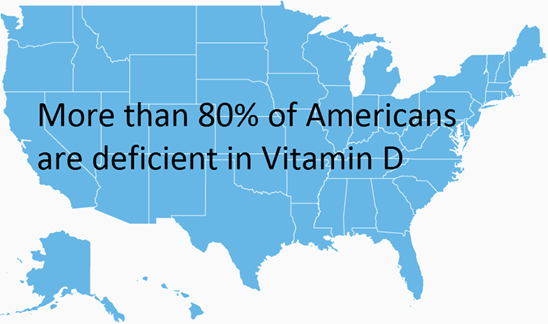

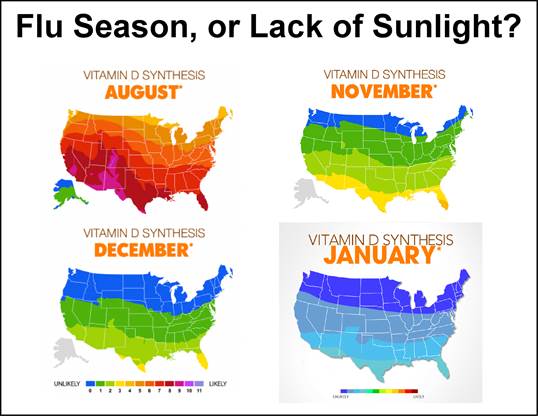

However, in modern times, a global trend of sun avoidance has contributed to widespread vitamin D deficiency. Public health campaigns emphasizing sun protection, urbanized lifestyles, and increased time spent indoors have led many individuals to receive insufficient sunlight exposure. Vitamin D deficiency is now recognized as a global public health issue, affecting over one billion people worldwide (Holick, 2007; Cashman et al., 2016). Consequences include increased risk for osteoporosis, impaired immune function, cardiovascular disease, and even mood disorders. Ironically, in moving away from the risks of excessive sunlight, societies have created new health challenges associated with inadequate sun exposure.

Conclusion

Sun therapy reflects a fascinating chapter in medical history where natural elements were harnessed as medicine, validated by a Nobel Prize, and later re-evaluated in light of modern science. While traditional heliotherapy is no longer widely practiced, its influence persists in contemporary phototherapy, offering safe and effective treatments under controlled conditions. The story of sun therapy underscores the evolving nature of medical practice, where initial enthusiasm, scientific innovation, and later risk assessment converge to shape how therapies are applied in modern healthcare.

References:

Cashman, K. D., Dowling, K. G., Škrabáková, Z., Gonzalez-Gross, M., Valtueña, J., De Henauw, S., … Kiely, M. (2016). Vitamin D deficiency in Europe: Pandemic? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(4), 1033–1044. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.120873

Daniel, T. M. (2006). The history of tuberculosis. Respiratory Medicine, 100(11), 1862–1870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.08.006

Grzybowski, A., Sak, J., & Pawlikowski, J. (2016). A brief report on the history of phototherapy. Clinics in Dermatology, 34(5), 532–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.05.002

Holick, M. F. (2007). Vitamin D deficiency. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357(3), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra070553

Holick, M. F. (2016). Biological effects of sunlight, ultraviolet radiation, visible light, infrared radiation and vitamin D for health. Anticancer Research, 36(3), 1345–1356. https://ar.iiarjournals.org/content/36/3/1345

Roelandts, R. (2002). The history of phototherapy: Something new under the sun? Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 46(6), 926–930. https://doi.org/10.1067/mjd.2002.121354

Narayanan, D. L., Saladi, R. N., & Fox, J. L. (2010). Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer. International Journal of Dermatology, 49(9), 978–986. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04474.x

Nobel Prize. (1903/2024). The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1903: Niels Ryberg Finsen. NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1903/finsen

Sunlight, outdoor light, and light therapy in disease management. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Sunlight,_Outdoor_Light,_and_Light_Therapy_in_Disease_Management