How Our Greatest Strengths Become Our Greatest Weaknesses

Human nature is inherently paradoxical. The very traits that empower individuals to succeed, lead, and create meaning in life often carry within them the seeds of their undoing. This reality, that one’s best qualities can also become one’s greatest liabilities reflects the profound wisdom of the yin-yang principle, a foundational concept in classical Chinese philosophy. Yin and yang are not simply opposites; they are complementary, interdependent forces that define and transform one another. Just as light is known only in contrast to darkness, strength becomes fully understood only when we recognize how it can slip into weakness.

Yin and Yang: Interdependent Forces

The Tao Te Ching teaches that the universe is governed by the continuous interplay of yin (receptive, passive, yielding) and yang (active, assertive, dynamic) energies. These forces are not antagonistic but mutually defining, each containing the seed of the other (Tao Te Ching, trans. Lau, 1963). This principle applies not only to the natural world but also to human psychology and character. In the same way that excess yang can result in aggression and burnout, or excessive yin in stagnation and withdrawal, personal strengths become vulnerabilities when pushed to extremes.

Aristotle expressed a similar idea in his theory of the “golden mean.” Virtue, he argued, lies between two extremes: deficiency and excess (Aristotle, trans. Irwin, 1999). Courage, for example, is the balance between cowardice and recklessness; generosity lies between stinginess and extravagance. When a trait exceeds its proper measure, it ceases to be a virtue. This echoes the yin-yang insight that balance, not absolute dominance, is the source of harmony and strength.

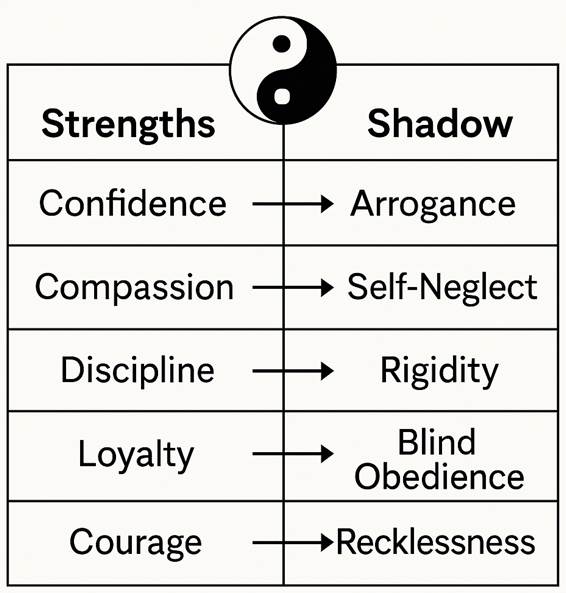

When Strength Turns to Weakness

Confidence and Arrogance

Confidence is essential to growth and achievement. It enables people to take risks, speak truthfully, and persist through adversity. Yet, unchecked confidence easily becomes arrogance, a refusal to accept feedback or recognize limitations (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The same force that drives leadership can blind a person to alternative perspectives, eroding relationships and stifling growth.

Compassion and Self-Neglect

Compassion is one of humanity’s highest virtues, binding individuals and societies through empathy and care. However, compassion without boundaries can lead to emotional exhaustion, codependence, or enabling harmful behaviors (Figley, 2002). In caring for others, one may neglect oneself, demonstrating how yin’s softness can dissolve into weakness if not balanced by yang’s firmness.

Discipline and Rigidity

Discipline builds resilience and mastery. But when discipline ossifies into inflexibility, it inhibits creativity and adaptability (Dweck, 2017). Martial artists often repeat the adage: “Be firm but not unyielding; flexible but not weak.” Like a tree that bends in the wind, human character must adapt to changing circumstances or risk breaking under pressure.

Loyalty and Blind Obedience

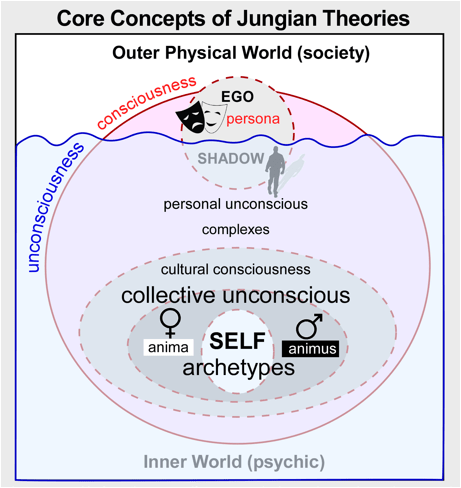

Loyalty fosters trust and cohesion. Yet blind loyalty, devotion without discernment, has fueled countless injustices throughout history. Jung (1959) warned that unexamined virtues often mask hidden “shadows,” unconscious impulses that distort behavior. Loyalty’s shadow is the surrender of critical thought, allowing unethical actions to persist under the guise of fidelity.

The Shadow and the Self

Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow offers a psychological lens for understanding this paradox. Every conscious virtue has an unconscious counterpart that, if unacknowledged, can manifest destructively (Jung, 1959). The perfectionist’s pursuit of excellence may hide a fear of inadequacy; the truth-teller’s bluntness may conceal a need for control. To achieve wholeness, what Jung termed individuation, individuals must confront and integrate these hidden aspects rather than deny them.

This process mirrors the yin-yang symbol, where each half contains a seed of its opposite. Strength and weakness are not distinct categories but fluid states that transform into one another depending on context, awareness, and intention.

Cultivating Balance and Wisdom

Recognizing the dual nature of virtue is not meant to discourage the cultivation of strengths but to deepen self-awareness. True wisdom lies in practicing moderation, context sensitivity, and ongoing reflection. Strategies for maintaining this balance include:

- Self-Observation: Mindfulness and introspection can reveal when a strength is tipping into excess.

- Feedback and Dialogue: Honest input from trusted sources helps counter blind spots.

- Flexibility: Adapting behavior to context allows traits to express themselves constructively rather than rigidly.

By embracing the yin-yang dynamic within ourselves, we learn to wield our strengths with discernment, preventing them from becoming self-defeating forces.

Harmony Over Extremes

The paradox that one’s best trait can also be one’s worst enemy is not a flaw in human design but a reflection of deeper universal patterns. As yin and yang continuously transform into one another, so too do strength and weakness. The path to mastery — of self, of relationships, of life — lies not in eliminating our shadows but in integrating them, not in suppressing our virtues but in balancing them. In doing so, we cultivate wisdom that transcends dualities and reflects the natural harmony of the Tao.

References:

Aristotle. (1999). Nicomachean ethics (T. Irwin, Trans.). Hackett Publishing. (Original work published ca. 350 BCE) https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780872204645

Dweck, C. S. (2017). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Ballantine Books. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-08575-000

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self-care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(11), 1433–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10090

Jung, C. G. (1959). Aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the self (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press. https://www.academia.edu/19686702/Carl_Jung_Aion_Researches_into_the_Phenomenology_of_the_Self_pdf_

Laozi. (1963). Tao te ching (D. C. Lau, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-13277-000