Staying Centered Amid Life’s Peaks and Valleys: A Holistic Perspective on Emotional Regulation and Meaningful Progress

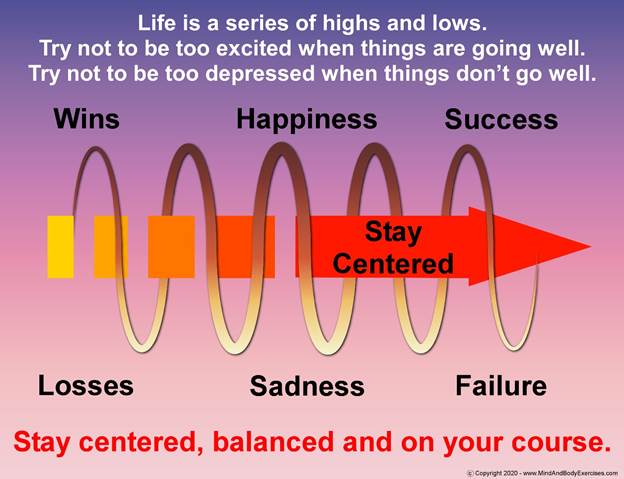

Life unfolds not as a straight line, but as a repeating rhythm of ascent and descent, wins and losses, happiness and sadness, success and failure. The image below captures this fundamental reality with clarity: oscillations occur, yet forward movement remains possible when one stays centered. The message is not to suppress emotion or ambition, nor to deny disappointment or grief, but rather to cultivate a steady internal reference point that allows movement through life’s inevitable fluctuations without becoming destabilized by them. This concept of remaining centered is deeply supported by psychology, neuroscience, and Eastern contemplative traditions alike.

From a physiological and psychological standpoint, emotional highs and lows are natural consequences of a nervous system designed to respond to changing environmental demands. Human beings are wired for reactivity where dopamine surges accompany perceived wins and successes, while losses and perceived failures activate stress-related systems such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (McEwen, 2007). These responses are adaptive in the short term; however, problems arise when individuals become excessively identified with either pole of experience. Chronic overexcitement, just like prolonged despair, pulls the individual away from internal balance and impairs judgment, health, and long-term well-being.

Psychological research consistently demonstrates that emotional extremes, whether positive or negative, can compromise decision-making and self-regulation. Heightened emotional arousal narrows attention, biases perception, and increases impulsivity (Gross, 2015). In moments of success, individuals may overestimate their abilities, take unnecessary risks, or become dependent on external validation. Conversely, during periods of failure or sadness, individuals may catastrophize, withdraw, or internalize defeat as a reflection of personal worth, rather than situational circumstances. The oscillating wave depicted in the image symbolizes this reality, while the arrow moving forward through the center represents the capacity to remain oriented despite these fluctuations.

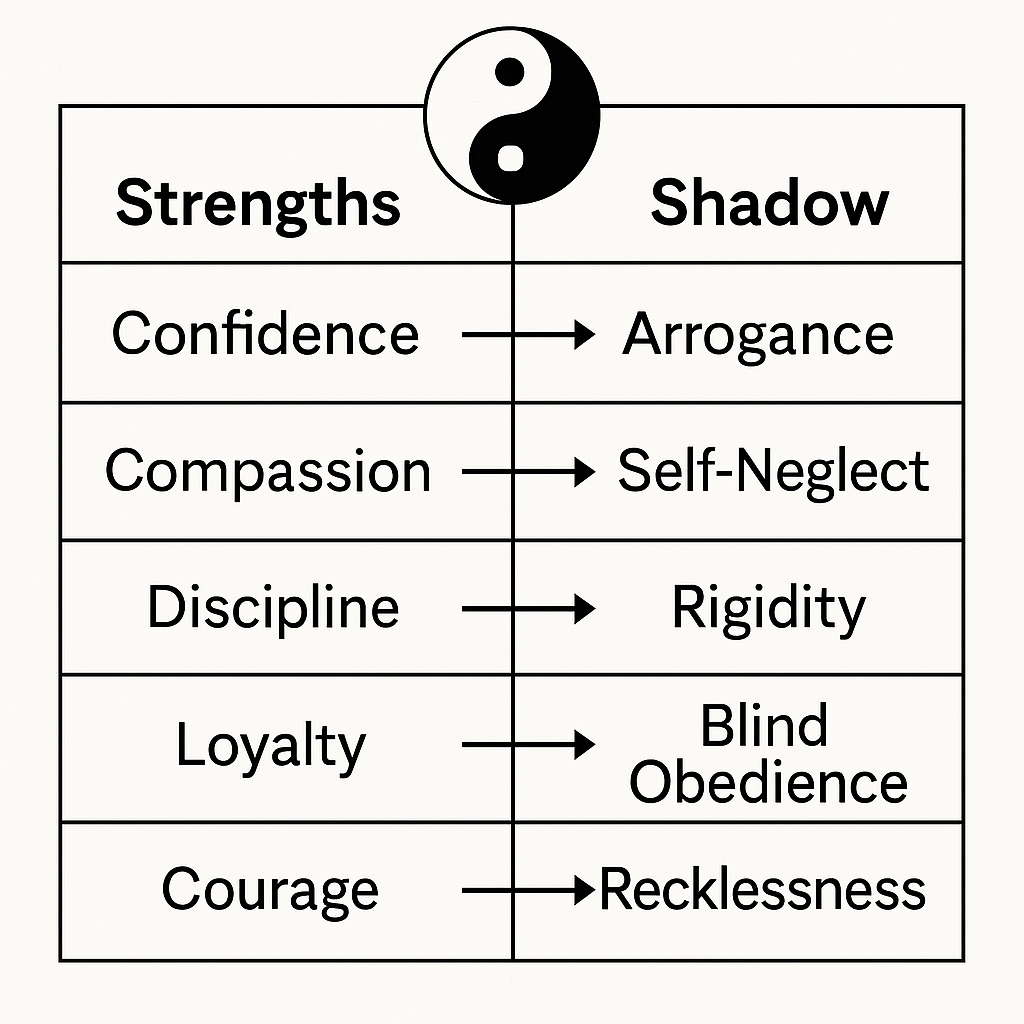

Eastern philosophical traditions have long emphasized this principle of equanimity. In Daoist thought, harmony arises not from eliminating opposites, but from maintaining balance between them. Yin and Yang are not moral categories of good and bad, but complementary forces that continuously transform into one another (Kohn, 2009). Excessive yang, manifested as overexcitement, ambition, or emotional inflation, inevitably gives rise to yin states such as depletion, exhaustion, or emotional collapse. Likewise, prolonged yin conditions of withdrawal, stagnation, or despair, contain the seed of renewed movement and growth. The centered path, therefore, is not a static midpoint but a dynamic alignment that allows one to pass through change without being consumed by it.

Modern psychology echoes this insight through the study of emotional regulation and psychological flexibility. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), for example, emphasizes the importance of maintaining values-based direction while allowing emotions to rise and fall without excessive attachment or avoidance (Hayes et al., 2006). The forward-pointing arrow in the image reflects this principle: progress is not contingent upon emotional state but upon consistent alignment with purpose and values. One can experience sadness without abandoning direction, just as one can experience success without losing humility or restraint.

Remaining centered also has direct implications for resilience and post-traumatic growth. Research indicates that individuals who are able to contextualize adversity, rather than becoming defined by it, are more likely to extract meaning and experience long-term psychological growth following hardship (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). The lows depicted in the image are not endpoints; they are part of the terrain. When individuals resist the urge to over-identify with failure or loss, they preserve the cognitive and emotional bandwidth necessary for adaptation, learning, and eventual renewal.

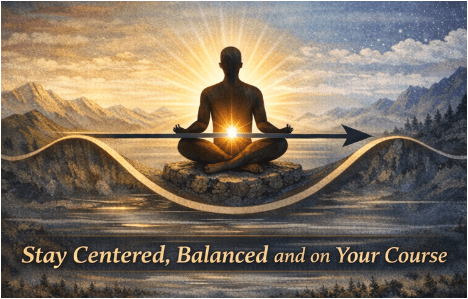

Importantly, staying centered does not mean emotional suppression. Emotional numbing and forced positivity are forms of imbalance in themselves. Rather, centering involves awareness, regulation, and proportional response. Practices such as mindful breathing, posture awareness, contemplative movement, and reflective inquiry help anchor the nervous system and restore coherence between body and mind (Porges, 2011). These practices create a physiological and psychological “center” from which individuals can observe emotional oscillations without being overwhelmed by them.

The image’s concluding message of “Stay centered, balanced and on your course” captures a profound truth: life will oscillate, but direction is a choice. Success and failure are transient states, not identities. Happiness and sadness are experiences, not destinations. When individuals learn to remain centered, they are less reactive, more discerning, and better equipped to navigate complexity with integrity. Over time, this centered approach fosters not only resilience but wisdom with the capacity to move forward with clarity regardless of circumstance.

Ultimately, the goal is not to eliminate life’s peaks and valleys, but to pass through them consciously. By cultivating internal balance, individuals transform volatility into momentum and uncertainty into opportunity. In doing so, they honor the full spectrum of human experience while remaining grounded, purposeful, and aligned with their deeper course.

References

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Kohn, L. (2009). Daoism and Chinese culture. Three Pines Press.

McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00041.2006

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01