A Life-Span Perspective on Inner Transformation

Human life unfolds through a series of roles, each carrying purpose, identity, and responsibility. In early and mid-adulthood, few roles are as consuming or as meaningful as that of parent and caregiver. Children, and often pets, become the gravitational center around which daily life, emotional energy, and long-term planning revolve. Yet these roles, by design, are temporary. When they change or dissolve, individuals are confronted not merely with loss, but with a profound existential question: Who am I when the role no longer defines me?

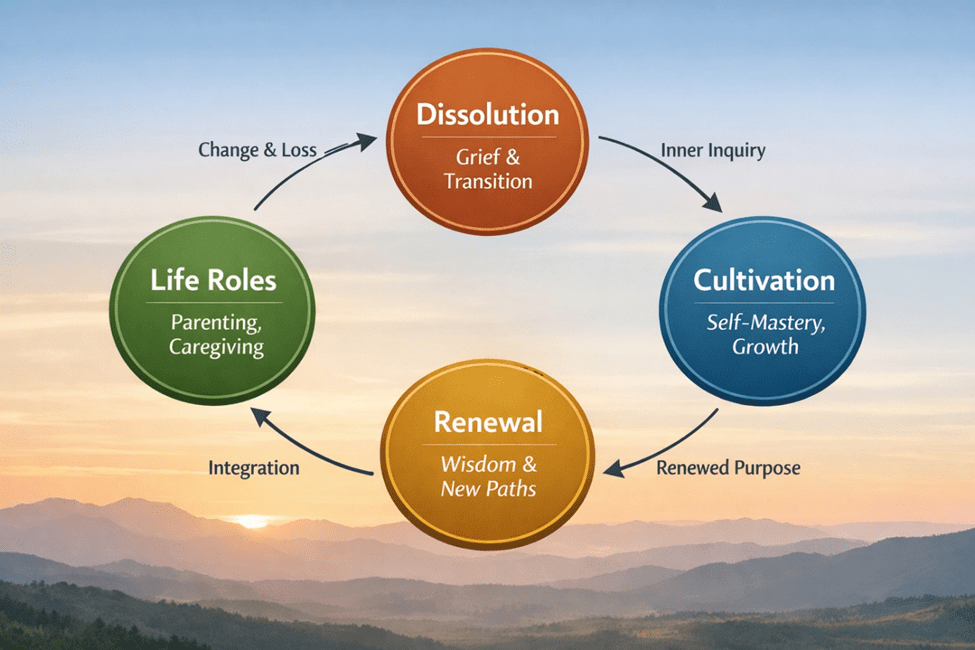

This experience is often described as role loss and is not a pathological condition, but a universal developmental passage. Whether it is children leaving home, shifting careers, aging bodies, or the death of companion animals, role transitions repeatedly invite (and sometimes force) inner reorganization. How one responds to these transitions determines whether the experience becomes a source of stagnation or a catalyst for transformation.

Parenting, Attachment, and Identity Enmeshment

Parenthood naturally restructures identity. Developmental psychology recognizes that adult roles are deeply intertwined with meaning, self-worth, and social validation (Erikson, 1950). Raising children requires sustained outward focus while protecting, guiding, financing, scheduling, and emotionally regulating for others. Over time, this external orientation can quietly eclipse internal development. Identity becomes fused with usefulness: I am needed, therefore I matter.

Pets often extend this caregiving role, especially as children age and become more independent. Companion animals provide continuity of responsibility, emotional regulation, and relational attachment, particularly during transitional phases when children are increasingly absent. Research confirms that pets frequently function as attachment figures and emotional stabilizers, especially in midlife and older adulthood (Brooks et al., 2018).

While these roles are meaningful and necessary, they can also delay an inevitable confrontation with the self, one that arrives when caregiving structures dissolve.

The Quiet Crisis of Role Loss

When children leave for college, careers, or families of their own, parents experience a second identity shift. Unlike earlier transitions, this one is often less publicly acknowledged and poorly ritualized. Western culture provides few frameworks for honoring the completion of a role, only its acquisition. The result is a subtle but destabilizing sense of redundancy, grief, and disorientation, commonly mislabeled as emptiness rather than understood as transition (Schlossberg, 1981).

The eventual loss of pets compounds this experience. Pets often represent the final daily structure of caretaking. Their passing can expose a stark silence, one that confronts individuals with unclaimed time, emotional bandwidth, and unresolved inner terrain. Grief, in this context, is not only about loss of companionship, but the collapse of a familiar role structure.

Without inner resources, these moments can devolve into distraction, compulsive busyness, or numbing behaviors. With awareness, however, they become invitations to a deeper stage of development.

Beneath the experience of role loss lies a deeper psychological reckoning: the quiet collapse of the illusion of control. Parenting and caregiving naturally foster the belief that vigilance, effort, and responsibility can shape outcomes, protect against loss, and stabilize the future. This belief is not naive; it is necessary. It allows parents to function, to commit fully, and to shoulder immense responsibility. Yet when children grow beyond parental reach or when beloved animals inevitably pass away, the limits of control become unmistakable. What dissolves is not merely a role, but the assumption that life can be managed through effort alone. This realization is often unsettling, but it is also liberating. It marks the threshold between external management and internal mastery, where meaning is no longer sustained by controlling circumstances, but by cultivating resilience, discernment, and acceptance within oneself.

Self-Mastery as Role Independence

Self-mastery begins where role dependency ends. Philosophical and psychological traditions alike emphasize that mature development involves shifting from externally assigned identity to internally cultivated authority. Carl Jung (1969) described this process as individuation: the lifelong task of becoming psychologically whole by integrating unconscious aspects of the self rather than living exclusively through social roles.

Similarly, Viktor Frankl (1959) argued that meaning cannot be sustained solely through responsibility to others; it must eventually be grounded in personal values, chosen purpose, and self-transcendence. When external roles fall away, the individual is challenged to generate meaning internally rather than inherit it from circumstance.

From an Eastern perspective, this transition mirrors long-standing teachings on detachment, not as disengagement from life, but as freedom from identity fixation. Taoist and Buddhist traditions emphasize that clinging to impermanent forms such as roles, relationships, identities, inevitably produces suffering. Liberation arises not from rejecting roles, but from recognizing that the self is larger than any single function it performs.

Inner Transformation Across the Life Span

Role loss, when consciously engaged, becomes a crucible for transformation. Developmental psychology frames later adulthood not as decline, but as a period of potential integration, wisdom, and generativity beyond productivity (Erikson, 1982). This stage invites reflection, synthesis, and the embodiment of lived insight rather than constant outward striving.

Practices associated with self-mastery often are rooted in reflection, physical discipline, breath awareness, ethical self-examination, and contemplative inquiry, providing structure when external roles disappear. These practices redirect attention inward, fostering resilience, emotional regulation, and coherence. Rather than asking, Who needs me now? the individual begins asking, What must I now cultivate within myself?

This shift aligns with post-traumatic growth research, which shows that major life disruptions often precede increases in psychological depth, appreciation of life, and existential clarity, when individuals engage adversity with intention rather than avoidance (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

From Role Loss to Role Renewal

Ultimately, the loss of roles is not an erasure of meaning, but a reorientation of it. The parent does not cease to be a parent; the caregiver does not lose compassion. Rather, these qualities are liberated from constant external demand and reintegrated as internal virtues such as wisdom, patience, discernment, and presence.

We most often earn value in life through service to others. Across every role we inhabit whether parent, caregiver, teacher, leader or otherwise, our words and actions inevitably affect other human beings. Yet while service gives life texture and meaning, it need not determine self-worth. Purpose does not collapse when a role dissolves, nor is identity dependent on what others think, say, or require of us. One of life’s enduring freedoms is the capacity to locate value within one’s own being, independent of role, recognition, or demand. When this freedom is realized, service becomes a choice rather than a necessity, and identity becomes grounded rather than contingent.

References

Brooks, H. L., Rushton, K., Lovell, K., Bee, P., Walker, L., Grant, L., & Rogers, A. (2018). The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1613-2

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed. W. W. Norton & Company.

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The structure and dynamics of the psyche (Collected Works, Vol. 8). Princeton University Press.

Schlossberg, N. K. (1981). A model for analyzing human adaptation to transition. The Counseling Psychologist, 9(2), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/001100008100900202

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01